2. Classical Chinese Gardens

2.1 Types of Classical Chinese Gardens

Classical Chinese gardens can be categorized into four types: imperial gardens, private residential gardens, temple gardens, and public gardens. Imperial gardens were primarily located in northern China. Private residential gardens were concentrated in the wealthy families of southern China. Temple gardens are now rare, and public gardens are mostly found in scenic areas, similar to public parks.

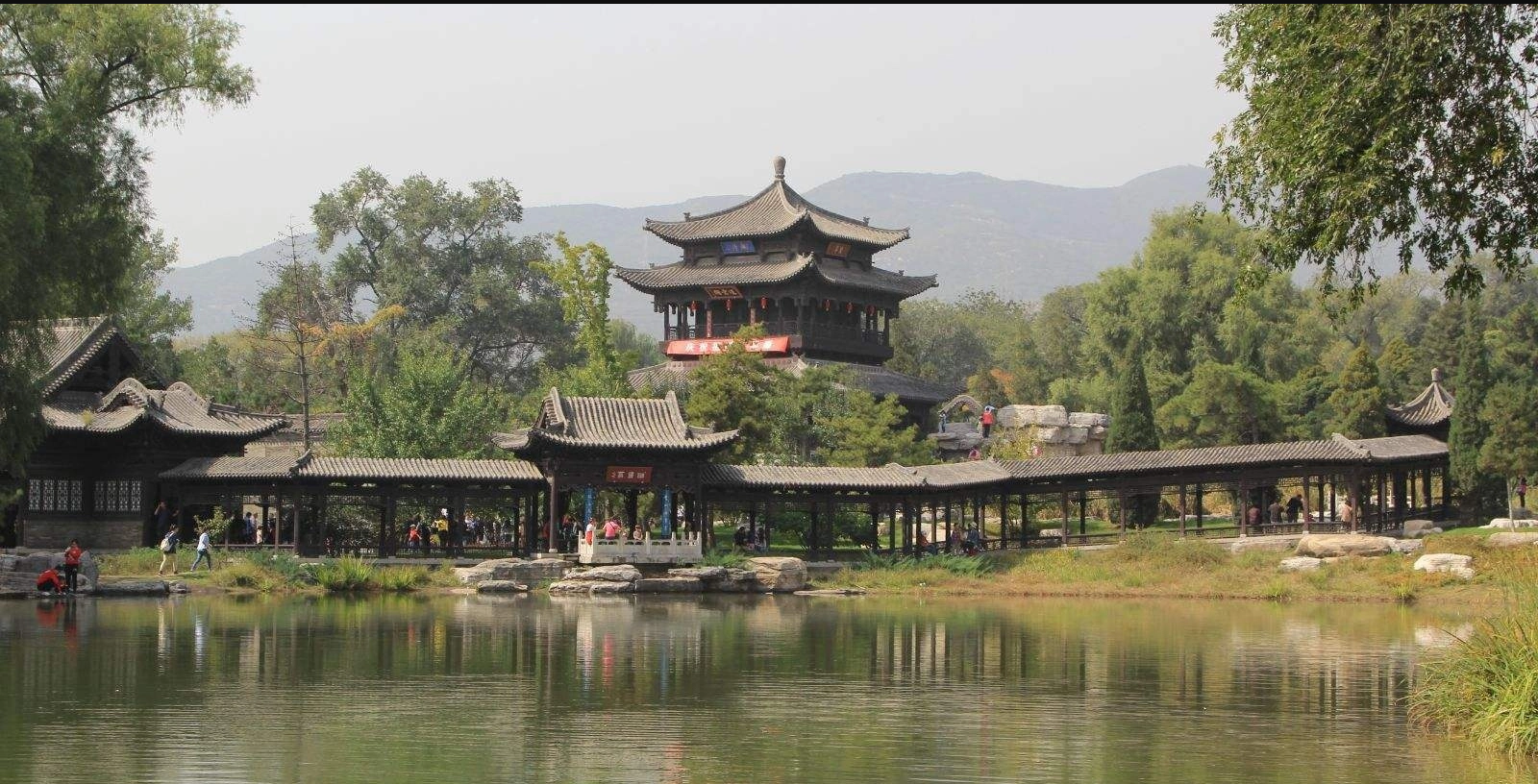

The history of Chinese gardens is over 3,000 years long. According to historical records, the first Chinese garden, also the earliest imperial garden, was the “Shangqiu Terrace” (沙丘苑台) built by King Zhou of Shang dynasty (1675 BC – 1029 BC), which included many animals and served as a place for his entertainment. The earliest gardens in China were imperial gardens. Beijing’s “Chengde Mountain Resort” (承德避暑山庄) is a typical and well-preserved example of an imperial garden.

Private residential gardens began in the Western Han dynasty (206 BC – 8 AD), with owners typically being nobles and wealthy individuals. As the economy developed, many private residential gardens appeared in the economically prosperous south. Most existing private residential gardens in southern China date back to the Ming (1368 AD – 1644 AD) and Qing (1616 AD – 1911 AD) dynasties, such as the Suzhou gardens and Shanghai’s Yu Garden (豫园).

Temple gardens emerged in large numbers after the introduction of Buddhism and the rise of Taoism in China. They were ancillary structures of temples, usually located deep in the mountains and utilized natural scenery with artificial embellishments. One of the largest existing temple gardens in China is the “Jinci”(晋祠) in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province.

Public gardens appeared around the Tang dynasty (618 AD – 907 AD), with “Qujiang Pool” (曲江池) outside ancient Chang’an city being a prominent example. Hangzhou’s West Lake (西湖) also became increasingly popular after the Tang and Song dynasties, becoming a public tourist spot and remains a recreational area for the common people of Hangzhou to this day.

2.2 Characteristics of Classical Chinese Gardens

Classcial Chinese gardens have three main characteristics:

Pursuit of Unity and Harmony with Nature: Chinese gardens invariably artistically recreate nature, imitating mountains and waters, drawing from natural forms to create a harmonious environment for human beings. The fundamental philosophical concept of garden creation in China is to embody the unity of man and nature in garden art by reaching the goal “Though made by man, it appears as if created by heaven” (虽由人作,宛如天开). Chinese garden arts focus on mountains and waters, with mountains representing the bones and waters representing the blood. The coordination of mountains and waters is emphasized, requiring mountains to have veins and waters to have sources, with water flowing around mountains and mountains enlivened by water.

Emphasis on Reflecting Human Interests and Spiritual Pursuits: Garden owners often imbued natural scenery with their ideals and beliefs, using natural elements to express their aspirations and tastes to satisfy their spiritual needs. For example, imperial gardens were often arranged to represent fairy mountains over the sea, reflecting the feudal emperors’ desire for immortality and eternal prosperity. Another example is the famous private garden in Suzhou, the “Humble Administrator’s Garden” (拙政园). Its owner, Wang Xiancheng, an Imperial Envoy and poet of the Ming dynasty (1368 AD – 1644 AD) was dissatisfied with court politics and experienced a tumultuous official life punctuated by various demotions and promotions. After quitting his last post, he began to work on the garden and named his garden to express his desire to retire from politics and adopt a hermit’s life to enjoy nature.

Subtle, Winding, and Varied Garden-Making Techniques: Chinese gardens oppose rigidity, monotony, and complete visibility, favoring concealed, subtle, and layered scenic elements. Specifically, garden design aims to fully exhibit diverse layers of natural scenery in a limited space, with clear distinctions between primary and secondary, varied heights, contrasting distances, and dynamic and static balance. A classical Chinese garden composed of four elements – waterways, rockeries, buildings, and pants – with walkways and corridors arranged to connect them while also situating guests to the grounds at the most advantageous viewing positions. These four types of features are arranged to enhance the natural topography and are arranged in relation to one another in such a way as to create a variety of views from any different angels. Each feature can serve simultaneously as a part of a view, a point from which to observe other scenes in the grounds, and a partition to separate sections of the garden.

2.3 Notable Examples of Classical Chinese Gardens

The three most well-preserved imperial gardens in China are the Three Seas 北京三海(Zhongnanhai中南海, Beihai 北海) in Beijing, the Summer Palace (颐和园), and the Chengde Mountain Resort (承德避暑山庄), with the Chengde Mountain Resort (承德避暑山庄), being the largest. Southern private residential gardens are concentrated in cities like Suzhou (苏州), Yangzhou (扬州), and Hangzhou (杭州), with Suzhou (苏州) having the most, hence it is known as the “City of Gardens.” The Canglang Pavilion (沧浪亭), Lion Grove Garden (狮子林), Humble Administrator’s Garden (拙政园), and Lingering Garden (留园) are the most famous, collectively known as the “Four Famous Gardens of Suzhou.” Additionally, Shanghai’s “Yu Garden”(豫园) is also extremely famous, known as the “Crown of Southeast Gardens,” with a history of over 400 years. Guangdong also has many private residential gardens, among which the “Keyuan” (可园) in Dongguan, “Yuyin Mountain House”(余荫山房) in Panyu, “Qinghui Garden”(清晖园) in Shunde, and “Twelve Stone Studios” (十二石斋) in Foshan are collectively known as the “Four Famous Gardens of Guangdong” from the Qing dynasty.

Watch this video about the classical gardens, including introduction of Chinese gardens, their functions, landscape design, and different elements (water, plants, architecture, etc.).