1. Traditional Chinese Holidays

Traditional holidays embody the stable psychology, emotions, and aspirations of the country or ethnic group, accumulate over a long period. Chinese traditional festivals contain the essence of Chinese traditional culture. The Chinese government officially recognized four traditional holidays: the Spring Festival, Qingming Festival, Dragon Boat Festival, and Mid-Autumn Festival. Each of these festivals is imbued with profound cultural significance.

1.1 Spring Festival and Lantern Festival

Spring Festival (春节), also widely known as Chinese New Year or Chinese Lunar New Year, is the biggest holiday in China. It’s celebrated not only by Chinese people in China but also by the Chinese diaspora around the world. Due to influence of Chinese culture in the history, many other Asian countries such as Korea, Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam also celebrate Spring Festival. Traditionally, the celebration of Spring Festival span from the first day to the 15th day of the first lunar month, and the 15th day of the celebration is known as the Lantern Festival (元宵节), which occurs on the full moon. This holiday marks the end of winter, the beginning of spring, and the start of a new year.

In 2006, the Chinese Spring Festival customs were officially listed in the Chinese national-level intangible cultural heritage by the State Council of China. In 2023, the 78th session of the United Nations General Assembly designated the Chinese Spring Festival as a United Nations holiday.

Like Thanksgiving and Christmas in the US, the Spring Festival is also a holiday for gift-giving, sharing delicious food, visiting family and friends, and enjoying a relaxing and joyful time. With a history spanning thousands of years, according to legend, people lit firecrackers, wore red clothing, stick red paper-cutting and couplets, and hung red lanterns to scare away a mythical monster called “Nian” (年, literally meaning “year”) as the new year began. Later people celebrated their victory over “Nian” with their families and friends.

A young Chinese man is posting the character 福 (luck) on the door, which is decorated with Spring Couplets on the walls and two red lanterns hung on the door.

Traditionally, Chinese people prepare for the celebration of the Spring Festival a month in advance. This preparation involves various activities such as shopping for new clothes, house decorations, and ingredients for the dinner on the eve. Before the festival, thorough cleaning will be conducted, symbolizing sweeping away misfortunes from the past year to welcome the new year afresh. Families post Spring Couplet (春联 chunlian), which are pairs of poetic lines or antithetical phrases written in Chinese calligraphy on red paper, around their doors to convey auspicious wishes and hopes for the coming year. In addition, homes are decorated with the character “福” (fu, meaning fortune or happiness), red paper cutout on windows, and red lanterns to create a festive atmosphere and pray for peace and auspiciousness in the new year.

On the eve of the Spring Festival, families gather for a lavish dinner, featuring fish, dumplings, rice cakes and other traditional dishes. Eating fish is an indispensable tradition because the pronunciation of fish “鱼 yu” in Chinese is similar to “surplus” (余 yu) symbolizing abundance and prosperity in the coming years and finance flourishing. From 8 pm till midnight, Chinese families watch the annual Spring Festival Gala (春节联欢晚会) broadcast by China Central Television (CCTV). This gala is a grand cultural showcase, featuring diverse performances by renowned domestic and international artists, including singing, dancing, traditional opera, acrobatics, talk show, and skits, blending the Chinese traditional culture with modern artistic achievements.

Following the gala and dinner, families often stay up late. At midnight, as the clock strikes twelve, Chinese people traditionally set off fireworks and firecrackers to ward off evil spirits and welcome the new year. Although firecrackers have deep roots in traditional Chinese culture, some local governments temporarily ban or designate specific zones or times for setting of firecrackers during the Spring Festival, aiming to reduce air pollution and minimize the risk of fires.

During the Spring Festival, Chinese people visit relatives and friends to exchange New Year greeting and wish each other happiness, health, and good fortune. Elders give red envelopes (红包 hongbao) with cash (压岁钱 yasuiqian, lucky money) inside to juniors as a symbol of blessing and good luck. With the widespread use of mobile payments, more and more Chinese people would like to send electronic red envelopes during the Spring Festival via phone, social media accounts or WeChat (a Chinese social media app). Some people choice to burn the first incense of the New Year in temples, praying for peace and hoping to bring blessings and good fortune home. Watching lion and dragon dances performances and visiting the temple fairs are also traditions in the Spring Festival.

In the last day of the Spring Festival (Lantern Festival), people light various lanterns, solve riddles written on them, and enjoy sweet dumplings (元宵yuanxiao, also called 汤圆tangyuan), symbolizing family reunion.

Symbolically, the Spring Festival represents not only family reunion but also the farewell to the old year and the welcoming of the new. It is an integral part of Chinese culture, reflecting family values and aspirations for a better life. The rich and diverse celebrations of the Spring Festival carry profound cultural significance, making it the most important traditional festival in China.

1.2 Qing-Ming Festival (清明节)/Tomb-Sweeping Day

Qingming Festival, also known as Tomb-Sweeping Day, Outing Festival, or the Third Month Festival, is a time for Chinese people to honour their ancestors and enjoy the beauty of nature. In 2006, Qingming Festival was listed as a national intangible cultural heritage in China. In 2008, it became a national public holiday, with a day off for the celebration.

The origins of Qingming Festival date back over 2,000 years. Qingming is the fifth solar term of the twenty-four solar terms[1], typically falling on the 15th day after the spring equinox, around April 4th to 6th each year.

The most important custom of Qingming Festival is tomb-sweeping. People visit their ancestors’ graves to clean the tombstones, remove weeds, and offer food, drinks, and paper money as tributes to express their respect and remembrance. As Qingming coincides with spring, it is also a time for outdoor activities. People go on outings, enjoy nature, and appreciate the blossoming flowers.

Flying kites is another traditional activity during Qingming Festival. The kites, soaring high in the sky, symbolize the release of worries and bad luck, bringing peace and good fortune. Other popular activities include tree planting, tug-of-war, swinging, etc.

The food customs of Qingming Festival vary by region. In southern China, people enjoy a traditional snack called Qing Tuan, made by mixing green plant juice with glutinous rice flour, filled with various sweet or savory fillings. These green-colored rice dumplings symbolize the breath of spring. Other traditional foods include Runbing and Ai Bing.

Besides China, Qingming Festival is also celebrated in countries such as Vietnam, South Korea, Malaysia, and Singapore. Qingming Festival holds deep cultural significance, embodying the values of respect for ancestors, family unity, and the harmony between humans and nature. It is a time to remember the past, cherish the present, and look forward to the future.

1.3 Duanwu Festival (端午节)/Dragon Boat Festival

Duanwu Festival, also known as Dragon Boat Festival, is a traditional holiday in China with a history spanning over 2,000 years. It falls on the 5th day of the 5th month of the lunar calendar.

During the Duanwu Festival, Chinese people prepare zongzi (粽子), which are sticky rice dumpling wrapped in bamboo leaves. The main ingredient in zongzi is glutinous rice, which gives them chewy texture. Zongzi vary in filling ingredients, reflecting regional and personal preferences. In northern China, zongzi are often sweet, filled with red bean pastes, jujubes (Chinese dates), and/or nuts. In southern China, zongzi are typically savory, filled with marinated pork belly, fresh meat, seafood, salted egg yolk, hams, and/or mushroom. Recent years, you even can find some innovative zongzi in the market which features unconventional fillings like chocolate, matcha, or other fusion flavors. Zongzi come in various shapes across different regions, including cone-shaped, cylindrical, and long strips, though the cone shape is the most common one.

Additionally, people make artificial and decorative zongzi-shaped sachets for children to play, wear, or decorate their house. The sachets contain cinnabar, realgar, aromatic herbs, wrapped in silk fabric, emitting a fragrant scent. They are adorned with colourful silk threads, knotted into various shapes, forming a string of diverse and charming ornaments.

It is also a tradition to hang the calamus (菖蒲, changpu) and ai (艾草, Chinese mugwort) leaves around homes. These leaves, as traditional Chinese medicinal herbs, contain volatile oils with a unique fragrance that effectively repel mosquitoes and insects. Therefore, ancient Chinese people believed that they would ward off evil spirits. People also bath in water boiled with mugwort leaves, and they drink realgar wine (雄黄酒, Xiong huang jiu), which is believed to protect against disease and evil spirits.

A Chinese woman is hanging the calamus and ai leaves on the door, which is decorated by the couplets

One of the most iconic activities during the festival is the dragon boat race with more than 2,000 years history, hence the name Dragon Boat Festival. Dragon boats are long, narrow wooden boat typically carved at the front into a dragon head shape and at the rear into a dragon tail shape. The boats are often adorned with intricate and colourful paintings. Dragon boats vary in length from several meters to tens of meters, depending on the numbers of crew members.

In 2011, dragon boat racing was officially listed as Chinese national intangible cultural heritage by the State Council of China, making its formal recognition. It has since turned into a formal competitive event with strict rules and regulations. A dragon boat team typically consists of 25 members, including 20 paddlers including a captain, one helmsman, one gong striker, one drummer, and two substitutes.

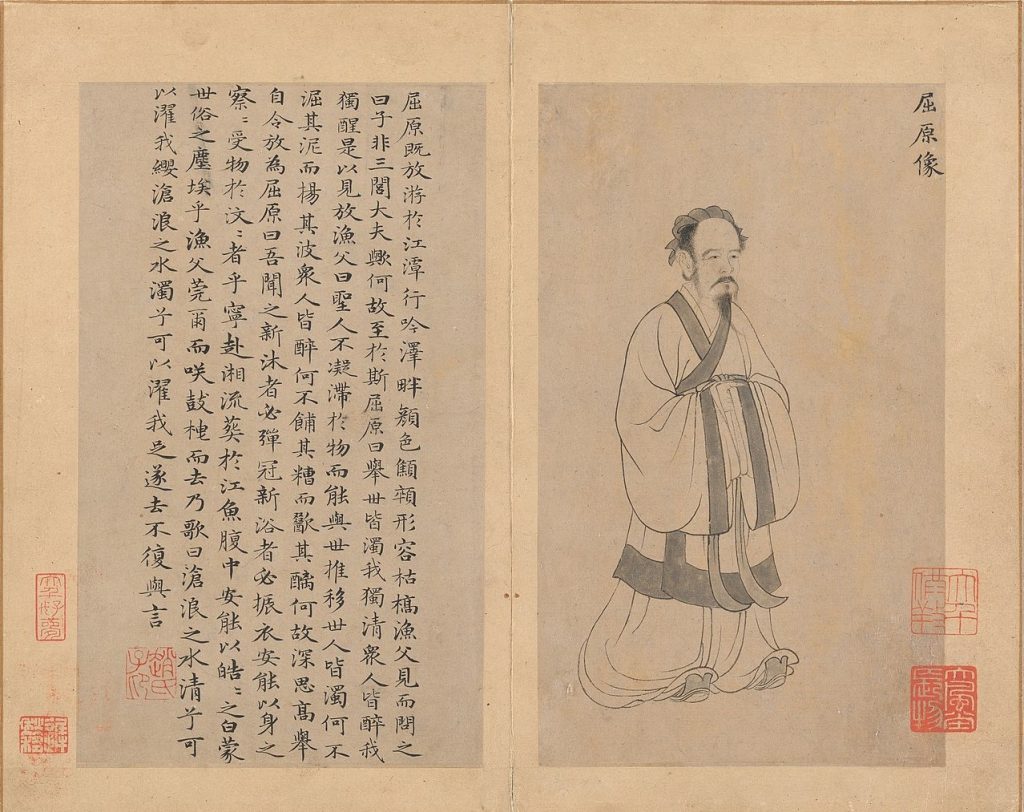

The Dragon Boat Festival is an ancient traditional Chinese holiday that originated during the Spring and Autumn Period and Warring States Period, with a history over 2,000 years. There are various legends and origins surrounding the festival, but the most common belief is that it commemorates Qu Yuan. Qu Yuan (339 BC – 278 BC) was a noble of the state of Chu and was a patriot, official, and poet. He opposed internal corruption and external aggressions against Chu, repeatedly urging rulers to enact reforms and resist invasions. However, his counsel went unheeded, leading to his exile. Upon hearing his homeland being invaded, Qu Yuan chose to drown himself in the Miluo River as an act of his patriotic despair. Local people, who revered Qu Yuan, rushed out in boats to save him or retrieve his body. To prevent fish from eating his body, they threw rice wrapped in bamboo leaves into the river. These traditions are said to be the origins of the dragon boat races and zongzi.

The Dragon Boat Festival is not only a time for festive activities and cultural traditions, but also an occasion to honor a historical figure who embodies patriotism and integrity.

1.4 Middle-Autumn Festival (中秋节)

The Mid-Autumn Festival, also known as the Moon Festival or Mooncake Festival, holds profound cultural significant in China. Celebrated on the 15th day of the 8th lunar month, typically falling in late September or early October in the Gregorian calendar, it marks a night when the moon appears its largest, roundest, and brightest moon of the year. In 2006, the festival was as a national intangible cultural heritage by the State Council of China, and in 2008, it became an official public holiday.

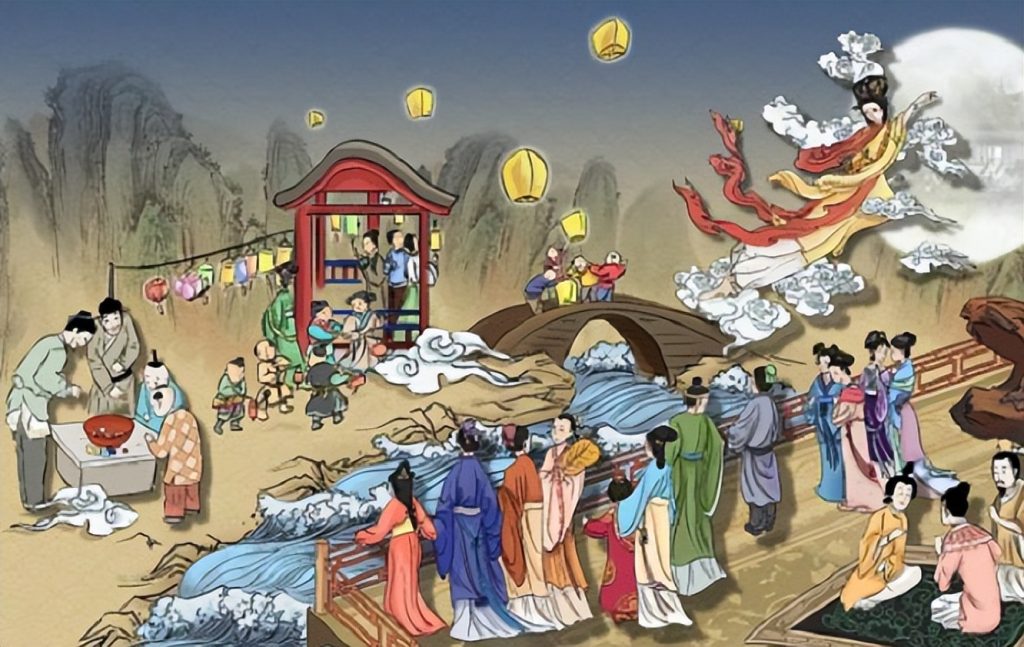

With a history dating back over 3,000 years, the Mid-Autumn Festival is associated with various legends and myths, the most famous being the story of Chang’e (嫦娥), the Moon Goddess. According to the legend, Chang’e drank an elixir of immortality and ascended to the moon, accompanied by a jade rabbit pounding the elixir of life under an osmanthus tree.

At its hearts, the festival is a time for family reunions, with loved ones traveling distances to get together. People bought and sent mooncakes as gifts to family and friends during the festival. The round mooncakes symbolize unity and completeness, filled with various ingredients, such as sweet bean paste, lotus seed paste, salted egg yolk, nuts, and even modern variations like chocolate or ice cream. Additionally, appreciating osmanthus and enjoying the food with osmanthus, like candies and cakes are also very popular in some regions.

Moon gazing is another tradition during the festival, where families gather outdoors to appreciate the full moon. This practice has inspired many Chinese poets and musicians in the history to create numerous poems and songs about moon. Lantern making and playing are also important activities in the festival. Some regions host lantern fairs and release sky lanterns and some craft “mandarin orange lanterns” with candles lit inside.

While the essence of the Mid-Autumn Festival remains consistent across China, different regions have their own unique customs and traditions. For example, Hong Kong features dragon and lion dances, and people in northern China play with “Tuer Ye (兔爷Rabbit Deity)” a toy depicted a rabbit-head figure clad in armor.

Tuer Ye (兔爷Rabbit Deity) with a history of over 380 years in Bejing area and now it’s listed in the intangible cultural heritages of Beijing

The Mid-Autumn Festival is not only celebrated in China but also in other Asian countries such as Vietnam, Korea, and Japan, each adding their unique customs to the festivities. It has also gained popularity in global communities with significant Chinese populations.

In essence, the Mid-Autumn Festival embodies values of family unity, gratitude, and harmony with nature, showcasing the profound depth of Chinese culture through its rich traditions and customs.

- The twenty-four solar terms are an essential part of the traditional Chinese calendar, dividing the year into spring, summer, autumn, and winter, each containing six solar terms. These terms not only reflect seasonal changes but also guide agricultural activities, with each term associated with specific farming tasks and customs. The system has been in use for over 2,000 years. ↵

The largest Chinese New Year parade outside Asia, in

The largest Chinese New Year parade outside Asia, in