1. Architecture in ancient China

Architecture in ancient China is a rich and diverse field that reflects the country’s long history, cultural values, and technological advancements. It has four distinctive characteristics:

Timber Framework: The most distinctive feature of traditional Chinese architecture is the use of wooden framework. Buildings were constructed with wooden posts, beams, and brackets, allowing flexibility and resilience against earthquakes. This method uses beams and columns as the skeleton in a dougong (斗拱interlocking wooden bracket) structure. The dougong structure is an intricate system of wooden brackets that transfer the weight of the roof to the columns. It is a crucial element in traditional Chinese architecture, providing both structural stability and decorative elegance, and is most commonly used in palaces, temples, and other high-status buildings.

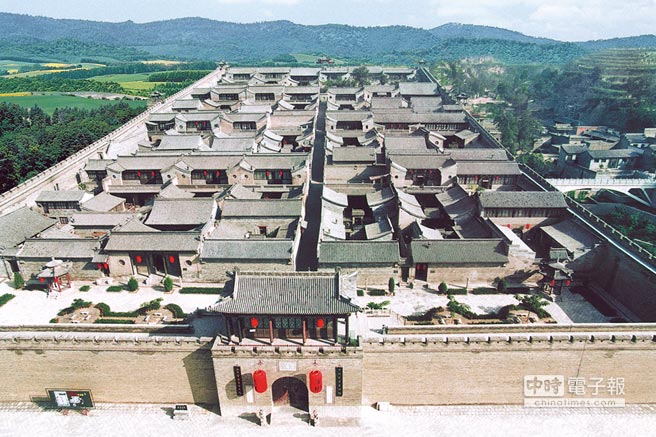

Layout Based on Units: In terms of layout, individual buildings are constructed based on the unit of a “bay” (间 jian), which is a space defined by the distance between two columns. These individual buildings are then grouped to form courtyards, and courtyards are further combined to create complex building ensembles. Whether individual buildings or building groups, the design is often square or rectangular, typically aligned along a north-south axis with the main buildings and subsidiary buildings arranged along east-west lines. Enclosing walls and corridors form a closed overall structure.

Wang Family Compound in Shanxi

Aesthetic Pursuit: In architectural aesthetics, there is a pursuit of stability, orderliness, and symmetry, emphasizing order and propriety. Major buildings are designed to be grand and imposing, often accentuated by minor buildings to highlight the main structures. Some buildings intentionally use the terrain to create varied elevations, allowing the orderly and symmetrical layout to exhibit rich and diverse changes in the overall appearance. As for Chinese garden architecture, the pursuit is not for neatness and symmetry but for winding paths, natural harmony, and poetic and picturesque qualities.

Artistic Achievement: In terms of artistic accomplishment, Chinese architecture often features large overhanging roofs, also known as “big roofs.” Palaces and temples, among other large buildings, also use high platforms, giving an impression of stability, solemnity, and grandeur. The shapes of building groups also emphasize clarity of primary and secondary elements, with rises and falls. From the main gate to the final courtyard, the layout resembles a drama or piece of music, with a prelude, climax, and finale.

Watch this short video which showed the dougong structure and the roofs of the halls in the forbidden city in Beijing.

1.1 Ancient Chinese cities

In traditional architecture, urban buildings are the most important category. According to archaeological discoveries, the earliest known Chinese city is the “Chengtoushan Ancient Cultural Site”(城头山) in Lixian County, Hubei Province, dating back over six thousand years. The ancient city site is well-preserved, with an urban area of 88,000 square meters (about 950,000 square feet) and wide moats outside the city walls.

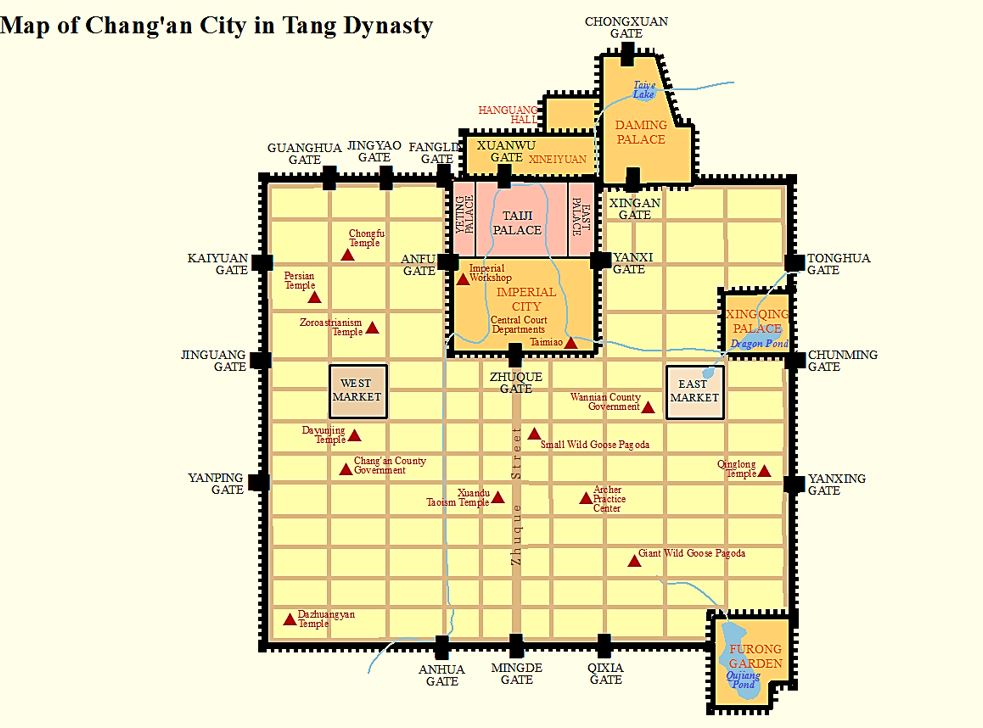

The largest ancient city in Chinese history was Chang’an City, the capital of Tang dynasty (618 AD – 907 AD). The entire city covered an area of 84.1 square kilometers (32.47 square miles), more than seven and a half times the size of the current Xi’an city (built in the Ming Dynasty) which is part of Chang’an City. It was even more than seven times the size of the Byzantine city, which was built a hundred years earlier. The ancient Chang’an City comprised three parts: the outer city (郭城), the imperial city (皇城), and the palace city (宫城). There were three city gates on each of the east, west, south, and north sides, with the “Mingde Gate” (明德门) in the middle of the southern side being the largest and serving as the main gate of the entire city. Within the city, there were 110 residential wards, as well as East and West Markets. There were 11 major streets running north-south and 14 major streets running east-west, six of which were over 100 meters (around 330 ft) wide. The main thoroughfare, Zhuque Street (朱雀大街), which connected Zhuque Gate (朱雀门) of the imperial city to Mingde Gate (明德门), was 150 meters (around 500 ft) wide.

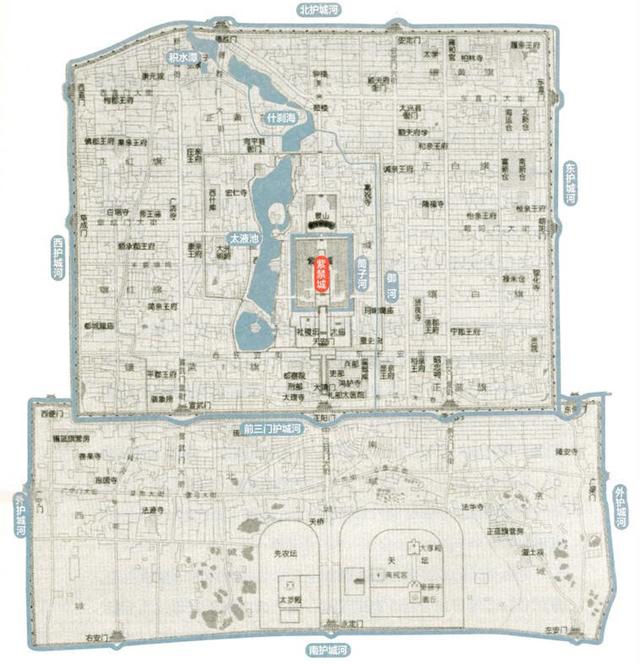

Beijing city during the Ming (1368 AD – 1644 AD) and Qing (1616 AD – 1911 AD) dynasties was the largest city in China during the late feudal period, covering an area of 60.2 square kilometers (around 23.24 square miles). It was rebuilt based on the Yuan Dynasty (1206 AD – 1368 AD)’s “Dadu City”(大都城)constructed by Kublai Khan (1215 AD – 1294 AD), forming a “凸” shaped layout. Old Beijing city consisted of three parts: the outer city, the inner city, and the palace city, each surrounded by moats. The present-day Forbidden City in Beijing was merely the palace city where the royal family resided during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. In Chapter 9 Cultural and Natural Heritage in China, we will specifically study the Forbidden City in Beijing.

Old Beijing City Map

Watch the video to travel back in time to the Tang Chang’an City.

1.2 Ancient Palaces

China has a feudal history spanned over a thousand years. With the rise of each dynasty, numerous palaces were constructed as exclusive places for emperors to reside and conduct governance. According to the book “Records of Residences through the Ages” (历代宅京记) written by the philosopher Gu Yanwu (顾炎武1613 AD – 1682 AD), the emperors of successive dynasties built countless palaces, with over twelve hundred named palaces documented. The design of these palaces emphasized grandeur and magnificence, reflecting imperial supremacy and serving the political needs of ruling.

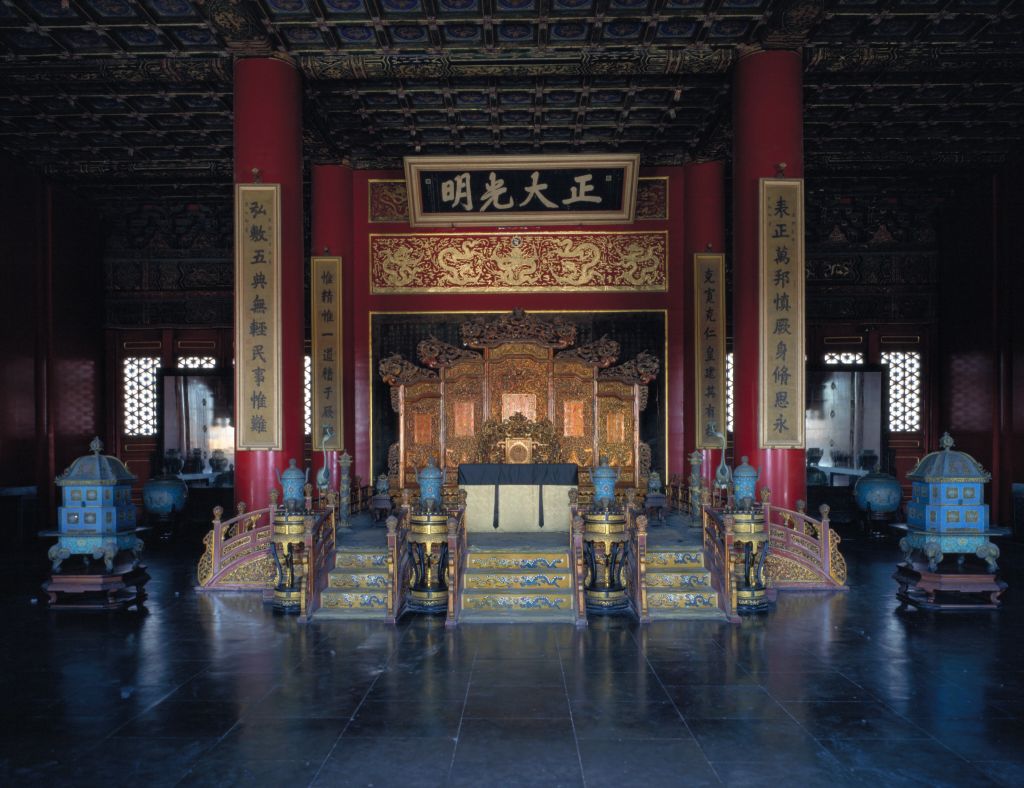

Palaces were typically arranged according to the supreme authority of the monarch, creating a hierarchical and orderly yet harmonious whole. For instance, the overall structure of the Forbidden City in Beijing follows the traditional “outer court and inner court” layout. The “Outer Court” includes the Three Great Halls (Hall of Supreme Harmony 太和殿, Hall of Central Harmony 中和殿, and Hall of Preserving Harmony 保和殿), where imperial ceremonies and governance took place, set against spacious courtyards to enhance the grandeur and majesty of the palace, inspire awe and respect for the supreme rulers. The “Inner Court” (内廷) consists of the Imperial Palaces (Palace of Heavenly Purity 乾清宫, Hall of Union Peace 交泰殿, and Palace of Earthly Tranquility 坤宁宫), where the emperor and the imperial family resided.

Interior of the Palace of Heavenly Purity 乾清宫

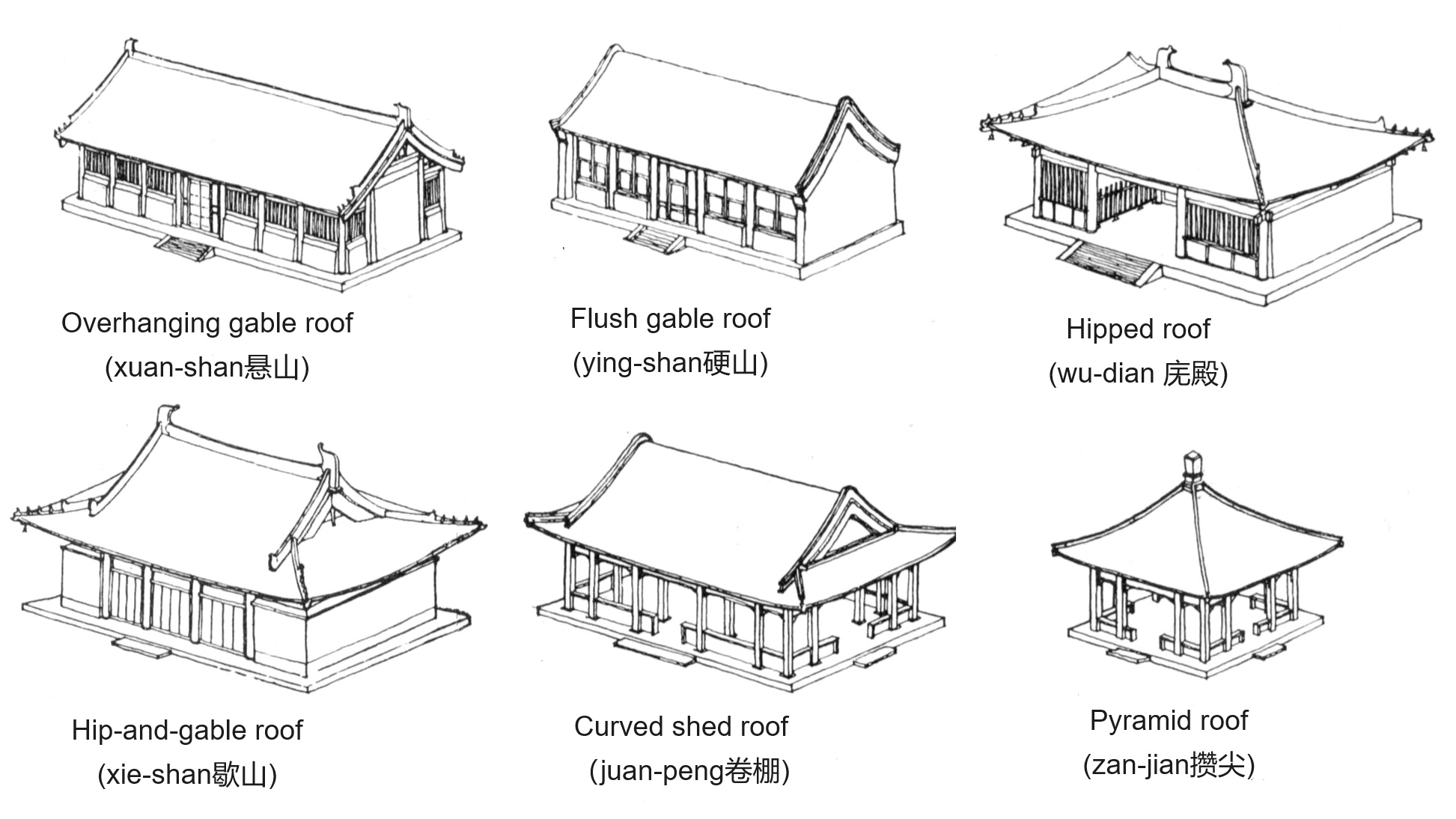

Chinese palace architecture adhered to strict hierarchical regulations, with the roof forms and decorations being particularly prominent. Traditional Chinese halls, including religious temples, employ six main roof styles: overhanging gable roof (悬山 xuan-shan), flush gable roof (硬山 ying-shan), hipped roof (庑殿 wu-dian), hip-and-gable roof (歇山 xie-shan), curved shed roof (卷棚 juan-peng), and pyramid roof (攒尖 zan-jian). These roof forms began to take shape during the Han Dynasty, as evidenced by excavated artifacts and Han Dynasty pictorial bricks (206 BC – 8 AD).

During its development, the double-eaved hipped roof (重檐庑殿)evolved into the most prestigious form of architecture. Only the main halls of imperial palaces and certain specially authorized buildings could adopt this style. Examples include the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the Palace of Heavenly Purity, and the main hall of the Imperial Ancestral Temple in the Forbidden City, Beijing. Next in rank is the hip-and-gable roof, commonly used for gate towers and city towers, such as the gate tower of Tiananmen. Other roof styles could be used for ordinary residences.

The classic upturned curve of the Chinese roof is due to several considerations. It increases the amount of light for the same rain protection; it helps to hold the shingles together; and it optimizes the flow of water, being more steeply pitched at the start of the slope where more gravity is needed and more shallowly pitched where the increased accumulation and momentum of the water helps the roof to shed water. These curves were sometimes further exaggerated for aesthetic effect.

Traditional Chinese Roofs

The overhanging gable roof (悬山 xuan-shan) features a double-sloped roof forming one main ridge (horizontal ridge) and four vertical ridges, with the roof extending beyond the gable walls on both sides.

The flush gable roof (硬山 ying-shan) has a double-sloped roof, but the gable walls are flush with the roof surface.

The hipped roof (庑殿 wu-dian) has a four-sloped roof, with the intersections forming one main ridge and four diagonal ridges, with the eaves and corners curving upwards and the roof surface slightly curved.

The hip-and-gable roof (歇山 xie-shan) combines two sloping and four sloping sides, featuring one main ridge, four vertical ridges, and four diagonal ridges.

The curved shed roof (卷棚 juan-peng), where the front and rear slopes intersect, uses an arched curved surface instead of a ridge.

The pyramid roof (攒尖 zan-jian) is a conical roof, with the base being circular, square, or polygonal, and is commonly used in pavilions and towers.

The decoration of palace roofs in Chinese ancient architecture is also meticulous. Various mythical creatures and animals adorn the roofs, collectively referred to as “roof beasts” (吻兽) or “auspicious beasts” (瑞兽). The number of these beasts on the central ridge signifies the rank of the palace, typically arranged in odd numbers, with a maximum of nine, except for the Hall of Supreme Harmony in the Forbidden City, which uniquely features eleven. At each end of the central ridge, there is a pair of roof beasts known as “chiwen 鸱吻” which is a mythical sea creature capable of extinguishing fire originating from the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 8 AD).

Besides chiwen 鸱吻, other ten roof beasts on the Hall of Supreme Harmony (太和殿) are immortals riding a phoenix, dragons, lions, seahorses, celestial horses (天马), fishtailed dragons (押鱼ya yu), guardian lions (狻猊 suan ni), xiezhi (獬豸 xiezhi), oxen, and immortal guardian (行什 hangshi), symbolizing harmony, auspiciousness, strength, integrity, stability, and the elimination of evil, reflecting the cultural psyche of China.