2. Taoism

Taoism, also known as Daoism, is a profound philosophical and spiritual tradition that originated in ancient China. Rooted in the foundational texts of the Tao Te Ching and the Zhuangzi, Taoism is characterized by its emphasis on living in harmony with the Tao, often translated as “The Way.” Attributed to the legendary sage Laozi, the Tao Te Ching is a foundational text that expounds the principles of spontaneity, simplicity, and the interconnectedness of all things. Another key Taoist text, the Zhuangzi, attributed to Zhuangzi, further explores the themes of relativity, the embrace of change, and the pursuit of inner freedom. Taoism advocates for a natural and effortless way of life, encouraging individuals to align themselves with the rhythms of the Tao. Practices such as meditation, Tai Chi, and Qigong are common in Taoist traditions, fostering physical and spiritual well-being. Taoism has also influenced Chinese arts, medicine, and the martial arts. Its philosophy continues to inspire individuals seeking balance, tranquility, and a deeper understanding of the interconnected nature of existence. The influence of Taoism still can be seen in China today. The ideas of yin-yang, the five elements, and the concepts of fengshui in Taoism still can be found in modern Chinese architecture, sculptures, painting, etc. During the Chinese festivals, people in the countryside still worship the Taoist deities, such as, the God of Wealth, the God of the Gate, and the God of the Kitchen.

2.1 Laozi and Tao Te Ching

Laozi, also spelled Lao Tzu, was born around 571 BCE in the State of Chu in ancient China. He was a great thinker and the legendary founder of Taoism, since he was traditionally credited with composing the foundational Taoist text, the Tao Te Ching. According to the legend, Laozi was a scholar who worked as the keeper of the Archives in the royal court of Zhou, which allowed him access to the classic works of that time. A story states that Laozi was recognized by the border guard of Hangu Pass when he decided to travel westward. He was asked to record his wisdom for the good of the country; otherwise, he would not be allowed to cross the border. Then he wrote Tao Te Ching (《道德经》). Laozi’s teachings emphasize the harmony of opposites, the spontaneity of nature, and the pursuit of simplicity as a means to attain spiritual enlightenment.

Laozi is considered the founder of Taoism, and his philosophy centers on the idea of simplicity, spontaneity, and aligning oneself with the natural order of the universe. In the Tao Te Ching, he offers profound insights into the art of governing, personal conduct, and the pursuit of wisdom. Laozi’s teachings have had a lasting impact on Chinese thought, inspiring generations of individuals seeking a harmonious and balanced way of life.

2.2 Tao, Ying-Yang, and Wuxing

Laozi, emphasizing the concept of Tao encapsulated his naturalistic philosophy primarily in the Tao Te Ching. This text serves as a foundational scripture of Taoism. Tao, often translated as ‘The Way’ or ‘The Path’, represents the natural order and the underlying principle of the universe, and is described as ineffable, formless, and all-encompassing. In its essence, the Tao is eternal, absolute, and beyond all space and time.; in its operation, it is spontaneous, everywhere, constant, and unceasing, always in transformation, going through cycles and finally returning to its root. The Tao takes no unnatural action (wuwei, 无为, translated as “effortless action” or “non-interference”), yet all things flourish. But Tao is nameless and Nonbeing itself—not in the sense of nothingness, but as not being any tangible thing. When an individual possesses the Tao, it becomes its “essential character/power” (Te). Taoism encourages individuals to align themselves with the Tao, fostering a sense of balance and harmony with the natural world.

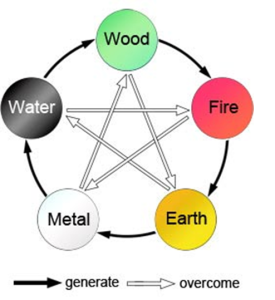

The symbol of Yin-Yang Five Elements Chart

According to Taoism, lasting harmony is achieved when yin (阴, the Female Principle) and yang (阳, the Male Principle) are well balanced. Yin-Yang is the fundamental concept in Chinese philosophy and cosmology, particularly within Taoism and traditional Chinese medicine. Represented by the iconic symbol of two interdependent and complementary forces, yin and yang embody the dualistic nature of existence, highlighting the dynamic balance between contrasting but complementary forces in the natural world and human life.

Yin is associated with qualities such as darkness, receptivity, passivity, femininity, cold, and stillness. It is often symbolized by the shaded portion of the Yin-Yang symbol. Yang, on the other hand, is associated with qualities such as light, activity, masculinity, heat, and motion. It is symbolized by the unshaded portion of the Yin-Yang symbol. The yin-yang ideal dictates that in marriage, there should be the harmony of the male (yang) and female (yin); in the landscape painting, that of mountain (yang) and water (yin); and in spiritual life, that of heaven (yang) and earth (yin). All things rotate, but they should do so in harmony.

Besides Tao and Yin-Yang, wuxing (五行, five elements) is another important concept in Taoism, which describes the dynamic interrelationships and interactions of the nature categorized by five fundamental agents or elements. These elements are Wood (木), Fire (火), Earth (土), Metal (金), and Water (水). The interactions between these five elements are traditionally depicted in a cycle known as the “Generating” cycle and the “Overcoming” cycle:

The generating cycle is as follows: Wood feeds Fire; Fire creates Earth (ashes); Earth bears Metal (minerals); Metal carries Water (condensation); and Water nourishes Wood. The overcoming cycle is as follows: Wood parts Earth (tree roots can break through soil); Earth absorbs Water; Water extinguishes Fire; Fire melts Metal; and Metal cuts Wood.

Wuxing serves as a framework for analyzing and explaining various phenomena, including the relationships between different elements in the human body and traditional Chinese medicine. The balance and harmony of these elements are considered essential for health, both in the physical and metaphysical sense.

2.3 Zhuangzi

Zhuangzi (c. 369–286 BCE), another influential Taoist philosopher, expanded upon Laozi’s teachings in his work named after him. The Taoism classical masterpiece “Zhuangzi” is a compilation of his thoughts, anecdotes, and allegorical tales that delve into profound insights about the nature of reality, the relativity of human perspectives, and the pursuit of spiritual freedom. To Zhuangzi, Tao is not merely nature; it is “self-transformed” nature. All things change at all moments. Every moment is different and conflicting, but Tao transforms and harmonizes them, combining them into a unity. It is in this stage, when everything follows its own nature and yet all forming a harmonious whole, that happiness and freedom are achieved. Zhuangzi’s philosophy often embraced paradox, playfulness, and a deep appreciation for the inexhaustible mystery of existence. His contributions added depth to Taoist philosophy, exploring the relativity of things, the fluidity of identity, and the idea of embracing change without resistance.

Zhuangzi wrote “Zhuangzi’s Dream of the Butterfly”, a famous philosophical allegory in his book “Zhuangzi” to discuss philosophical questions about reality and dreams, existence and illusion. In the narrative, Zhuangzi dreams of transforming into a butterfly. In the dream, he experiences the sensations of being a butterfly, fluttering among flowers. However, upon waking up, he begins to question whether he is Zhuangzi who dreamt of being a butterfly or if he is currently a butterfly dreaming of being Zhuangzi. He reflects on the blurred boundaries and distinctions between the two, raising the question of whether he is in reality or still within the dream. Through the allegory, Zhuangzi expresses his philosophical perspective, emphasizing that our perceptions of reality are subjective and relative, and the true boundaries may be more indistinct than we perceive. The allegory has had a profound influence on Chinese philosophy and has been widely cited and interpreted by later philosophers and cultural thinkers.

2.4 Taoism as a Religion

Taoism evolved not only as a philosophical system but also as a religious tradition with temples, rituals, and deities. Taoist religious practices involve the worship of various deities, including Laozi himself, and the cultivation of internal alchemy to achieve spiritual immortality. Taoist rituals, often centered around nature and cosmic forces, reflect a blend of philosophical principles and religious observances.

Religious Taoism worships Laozi under the name “Supreme Old Lord (太上老君). Since Laozi’s family name is Li which is also the family name of the emperors of Tang Dynasty (618-907). The emperors of Tang Dynasty traced their ancestry to Laozi which provided a testament to Laozi’s impact on Chinese culture. Taoism as a religion was formed toward the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220). Zhang Daoling, an alchemist, founded a brand of Taoism called Tianshidao (the doctrine of celestial master) in Sichuan province. During the Yuan Dynasty (1206-1368) Zhang Daoling’s thirty-eighth generation grandson with the name Zhang Yucai, transferred all southern schools of Tianshidao to Zhenyidao. Thus, since then, the two major sects of religious Taoism were founded and developed until today.