3. Religious Architecture in China

In ancient China, religious rituals were crucial across all societal strata. Many of the best-preserved and most remarkable ancient structures to date are religious buildings in China. The main types of religious architecture in China include temples, shrines, ancestral halls, and pagodas. These buildings resemble palaces and residential buildings, sharing similar traits such as prominent axial lines, symmetry, and a layout with various courtyards, creating a visual balance through varied heights and clear hierarchies. Due to their religious nature, these buildings feature more regular and stringent designs, often displaying highly stylized layout.

3.1 Buddhism Architecture

Among surviving religious buildings in China, traditional shrines, Taoism and Buddhist structures predominate, with Buddhist temples being the most numerous. Chinese Buddhist architecture originated from India. By the Tang Dynasty (618 AD – 907 AD), these temples’ layouts and hall structures had evolved to closely resemble Chinese palaces. Many existing Buddhist temples were either renovated or rebuilt during the Ming and Qing Dynasties after the fourteenth century. Their typical layouts include a central axis lined with “mountain gates (山门)” leading to a sequence of courtyards with the main halls surrounded by other building on either side. Buddhist architecture also imbues religious significance; for instance, the 108 steps lead to the “Mahavira Hall” at Pusading and “Nanshan Temple” in Wutai Mountain represent worldly 108 afflictions mentioned in the Buddhist scripture. By the time one reaches the top, all their troubles are believed to be eliminated. Further details on Buddhist pagodas will be discussed in section 3.3.

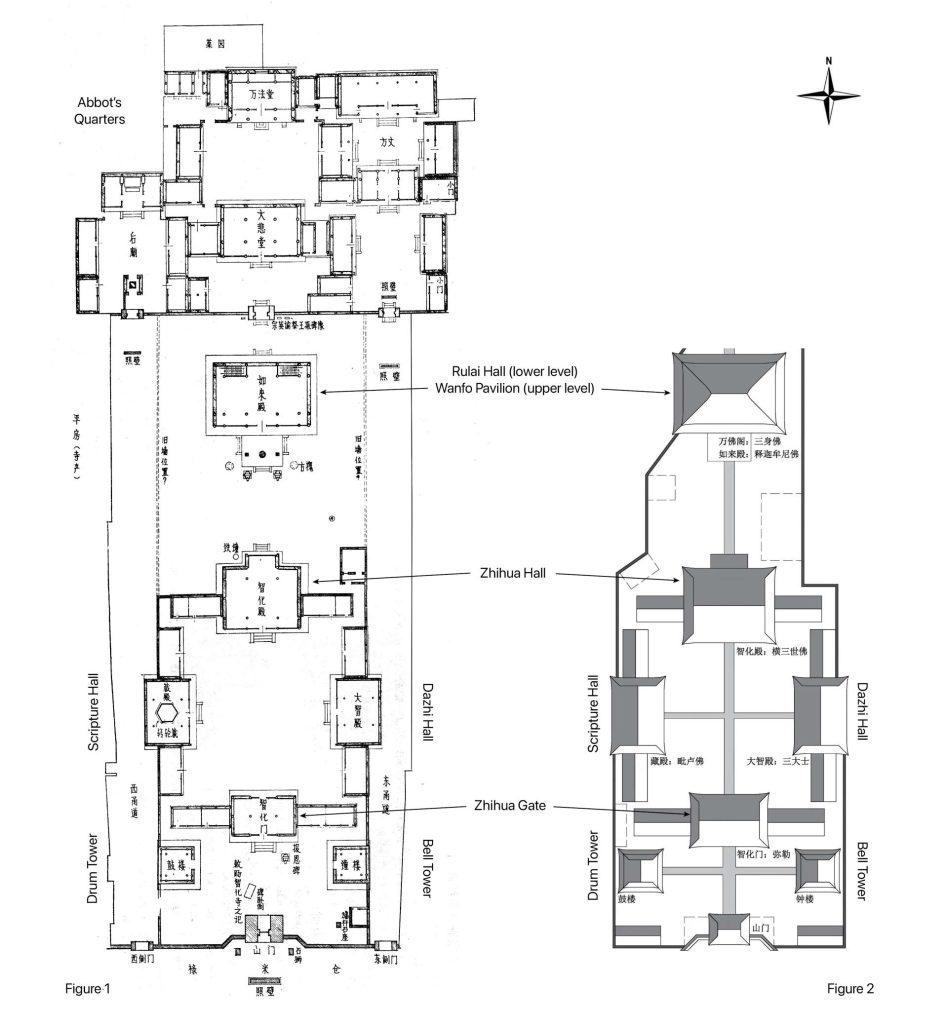

The layout of Beijing Zhihua Temple (figure 1 site plan made in 1931 and figure 2 the current site plan)

3.2 Taoist Architecture

Taoist temples are the second most abundant religious structures in China. These temples emulate Buddhist temple architecture, but their decorations and murals depict Taoist themes and stories. General layouts of Taoist temples include a “mountain gate”(山门), “Three Purities Hall”(三清殿 where enshrines the orthodox gods of Taoist theology), “Four Patrols Hall” (四御殿 where enshrines four esteemed deities in Taoist celestial hierarchy), followed by halls dedicated to Taoist deities and other ancillary buildings. For example, Beijing’s famous Taoist temple “White Cloud Temple”(白云观) is arranged with a layout that includes a ceremonial arch (牌坊 paifang), mountain gate (山门), Lingguan Hall (灵官殿 where enshrines the divine protectors in Taoism), Jade Emperor Hall (玉皇殿), Seven True Hall (七真殿 where enshrines the seven masters of Quanzhen Taoism), Qiu Zu Hall (丘祖殿 where enshrines Master Qiu Chuji 丘处机), and Four Patrols Hall (四御殿).

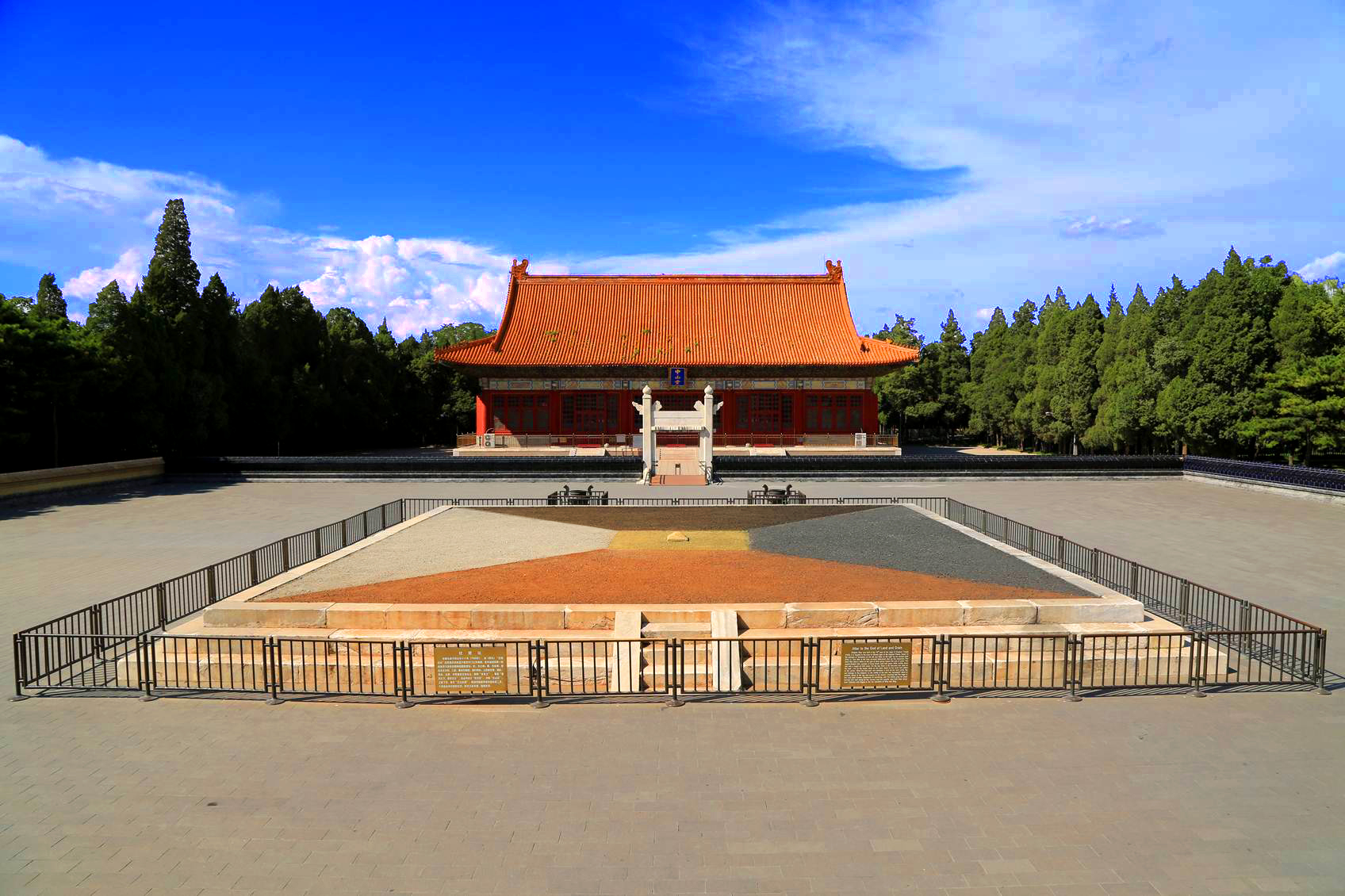

Ritual architecture in China were built to worship Heaven and Earth, the emperors, significant historical figures, or ancestors. The designs of these kinds of buildings present profound Chinese cultural connotations and adhere to traditional ceremonial requirements. Representing the epitome of such architecture are Beijing’s Temple of Heaven (天坛), Altar of Earth (地坛), Altar of the Sun (日坛), Altar of the Moon (月坛), and Altar of Agriculture (社稷坛), designed for imperial worship. Reflecting traditional Chinese concepts of “south for Heaven and north for Earth” (天南地北) and “the sky is round, and the earth is square” (天圆地方), the Temple of Heaven is located to the south of Beijing, designed in circular form, while the Altar of Earth is to the north, designed in a square format. Similarly, adhering to the concept of “east for the Sun and west for the Moon,” the Altar of the Sun is situated east of Beijing, and the Altar of the Moon in the west. The Altar of Agriculture serves to pray for prosperous national fortunes and abundant harvests. The altar is covered by five patches of soil with five different colors (green in the east, red in the south, white in the west, black in the north, and yellow in the center), symbolizing all lands under Heaven belonging to the emperor.

Alter of Agriculture, Beijing, China

The overall layout of these ritual buildings adopts a courtyard arrangement reminiscent of palatial or residential styles. In traditional Chinese architectural terminology, the unit of the Chinese traditional building which is the courtyards separated by buildings and corridors along the central axis is called “jin”(进). Temples dedicated to imperial ancestors are grander in scale, featuring at least three jins, or even more, forming majestic complexes of ancient architecture. For instance, the Confucius Temple (孔庙) in Qufu, Shandong Province, emulates the layout of an imperial palace, spanning nine jins to underscore Confucius’s pivotal historical status in China. The Zhongyue Temple (中岳庙) on Mount Song in Henan Province comprises as many as eleven jins, alongside the Confucius Temple in Qufu and the Forbidden City in Beijing, collectively renowned as the “Three Great Ancient Architectural Complexes of China.”

3.4 Pagodas 塔 (ta)

China currently boasts over three thousand pagodas, predominantly religious structures, primarily associated with Buddhism. However, in later historical developments, Taoist and Confucian literati also constructed pagodas, some of which were situated in picturesque landscapes, approaching the realm of scenic architecture.

The pagoda originates from India’s “Stupa,” translated in Chinese as “浮屠” (futu) or “浮图” (futu), initially used to enshrine relics of Sakyamuni Buddha, such as bones, teeth, or hair. Later, they were also used to house Buddhist scriptures or as burial sites for revered monks and masters, evolving into “Buddhist pagodas” or “funerary pagodas”. By the Tang Dynasty (618 AD – 907 AD), Buddhist pagodas integrated Chinese architectural styles, resulting in various plan layouts like hexagonal, octagonal, and diamond-shaped forms. Pagodas were constructed using materials ranging from wood initially, to later include stone, bronze, iron, glazed tiles, ceramics, and precious metals like gold and silver. Pagodas typically have an odd number of storeys, with seven, eleven, and thirteen being common.

Shaolin Pagoda Forest, Shaolin Temple, Henan province, covering an area of nearly 151, 000 square feet. It is the largest and most numerous ancient pagoda complex in China. There are 241 brick and stone funerary pagodas from seven dynasties.

Types of Chinese Pagodas

According to the shape of the pagodas, they are generally classified into five types:

- Multi-eave style (阁楼式): It imitates traditional Chinese multi-storey wooden frame buildings. It features spacious intervals between floors, each with windows, brackets, overhanging eaves on the exterior, internal staircases, and providing vantage points for distant views. Examples include the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda (大雁塔) in Xi’an, the Wooden Pagoda in Ying County (应县木塔), and the Tiger Hill Pagoda (虎丘塔) in Suzhou.

- Dense-eave Style (密檐式): Originating from the Northern Wei Dynasty (383 AD – 534 AD), it is mostly made of bricks and stones. Its distinctive features include an exceptionally tall first storey at the base of the pagoda, adorned with niches, Buddha statues, windows, etc. From the second storey upwards, the floors are closely spaced, with tightly packed eaves, lacking windows or featuring only small decorative windows. These pagodas are solid inside without staircases, preventing ascent. Examples include the Tianning Temple Pagoda (天宁寺) in Beijing and the White Pagoda in Liaoyang (辽阳白塔) .

- Lama Style (喇嘛式): Distributed mostly in Mongolian and Tibetan regions, this style closely resembles India’s stupas. It features a square base, a rounded body with a large belly, a pointed top, and a white-painted surface. Examples include the White Pagoda of Miaoying Temple (妙应寺白塔) in Beijing, the North Pagoda of Beihai Park (北海公园北塔) in Beijing, and the White Pagoda in Slender West Lake (瘦西湖白塔) in Yangzhou.

- Flower Style (花塔): Appearing during the Tang Dynasty Dynasty (618 AD – 907 AD), these became less common after the Yuan Dynasty (1206 AD – 1368 AD). The distinguishing feature is the upper half of the pagoda constructed to resemble lotus petals or adorned with carvings of niches, Buddha statues, flowers, etc., resembling a flower from afar. Famous examples include the Flower Pagoda of Guanghui Temple (广惠寺花塔) in Zhengding County, Hebei Province, and the Flower Pagoda of Wanfo Hall (万佛堂花塔) in Fangshan, Beijing.

- Vajra Throne Style (金刚宝座塔): This type of pagoda consists of five small pagodas built on a rectangular or square high platform to honor the five Buddhas of the Vajra realm. They are exceedingly rare in China today, with examples including the Wuta Temple (五塔寺), Biyun Temple (碧云寺), Huang Temple (黄寺) in Beijing and the Wuta Temple in Hohhot (呼和浩特五塔寺), Inner Mongolia.

Wuta Temple in Hohhot (呼和浩特五塔寺), Inner Mongolia, China