Chapter 3: Promoting Self-Determined Motivation for Physical Activity: From Theory to Intervention Work

Chapter Overview

Introducing Motivation: “What Do I Do, and Why?”

An Overview of Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

Autonomous and Controlled Motives to Be Physically Active

Figure 3.1

Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration

The Role of the Social Environment

Table 3.1

Overview of SDT as Applied in Exercise and Other Physical Activity Contexts

Figure 3.2

Practical Application #1: An Application of Self-Determination Theory in the Context of Group Cycling Exercise Classes

Practical Application #2: Application of Self-Determination Theory in the Context of Group Walking in Retirement Villages

Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Learning Exercises

Promoting Self-Determined Motivation for Physical Activity: From Theory to Intervention Work

Chapter Overview

- Motivation is one of the most important concepts to understand for those interested in promoting health and well-being via participation in physical activity.

- In this chapter, we will explore how motivation has been defined, and focus on self-determination theory as one of the most popular and useful theories that has been applied to the study of motivation to be active.

Introducing Motivation: “What Do I Do, and Why?”

- Motivation represents the impetus or urge to move and is often thought of as a quantifiable entity.

- Definitions of motivation have focused on the direction, origin, intensity, and persistence of behaviors.

- In recent decades, research in this field has shifted focus from quantity to the quality of motivation. Whereas the quantity of motivation refers to how much motivation one has, quality of motivation refers to the reason why an individual is motivated to engage in the target behavior.

- Understanding the reasons for motivation tells us more about what is regulating the behavior than simply knowing how much there is; hence motivational reasons are sometimes referred to as motivation regulations or behavior regulations.

An Overview of Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

- SDT recognizes that being motivated by lower quality reasons can be detrimental for the individual’s health and well-being, even if the person engages in the behavior

- Decades of SDT research has generally found that the same factors that can stimulate more autonomous interest in an activity are also those that promote health and wellness.

- When motivation is optimized, individuals are likely to take part in physical activities because they value, benefit from, and enjoy the activity.

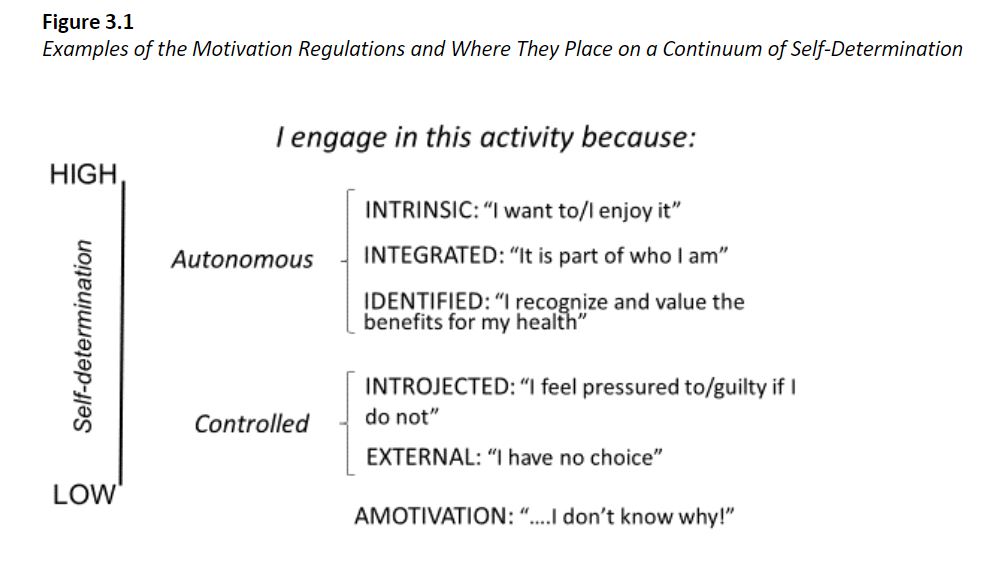

Autonomous and Controlled Motives to Be Physically Active

- SDT proposes that healthy choices are more likely to be made and sustained when behavior is autonomous, doing an activity willingly because you want to engage in the behavior for its own sake (intrinsic motivation) or because it is part of your identity (integrated motivation).

- Individuals will sometimes engage in behaviors for non-volitional reasons. Introjected motivation is underpinned by internal pressures or contingencies, such as fear, guilt, or contingent self-worth.

- Amotivation describes a state in which the individual lacks intention or reason to continue. If amotivation becomes more prominent than controlled or autonomous regulations then it is likely that the individual will disengage from the behavior, or not start at all.

- It is often the case that multiple motivation regulations underpin behavior. However, people will experience most benefit when the motivations are all, or predominantly, autonomous.

Figure 3.1

Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration

- SDT proposes that the degree to which autonomous and controlled motivations are supported or undermined depends on the extent to which three basic psychological needs are satisfied or frustrated.

- The three needs highlighted by SDT are competence, autonomy, and relatedness.

- When needs are frustrated, behavioral engagement is likely to be controlled by introjected or external regulations, which subsequently leads to an array of negative consequences, as previously outlined.

The Role of the Social Environment

- SDT has particular utility as an approach to understanding motivation in exercise and other forms of structured physical activity, as the theory identifies how the social environment can be optimized to create the most appropriate conditions for adaptive motivation to ensue.

- If the social environment is characterized by need supportive strategies, the individual will be more likely to experience need satisfaction, which leads to more autonomous motivation for the activity, and in turn, adaptive outcomes.

- When the social environment is characterized by need thwarting strategies, needs are likely to be frustrated, motivation is likely to be controlled, and maladaptive consequences are predicted to ensue.

Table 3.1

Descriptions of Need Supportive, Thwarting, and Indifferent Behaviors in Physical Activity Settings

|

Supportive |

Thwarting |

Indifferent |

|

Autonomy – Acknowledge, recognize, and nurture the inner motivational resources of others – Offer meaningful choices – Attempt to understand others’ perspective – Give personally meaningful rationales – Encourage input into decision-making – Give opportunities for self-initiated behavior |

Autonomy – Pressure others to think, feel, and behave in certain ways – Dismiss or devalue others’ perspectives – Apply excessive personal control in situations – Use coercive strategies to control how tasks are performed – Dismiss or devalue others’ perspectives |

Autonomy – Negligence or inattention towards individuals’ perspectives and their inner motivational resources |

|

Competence – Guide individuals to feel capable of tackling challenges or experiencing meaningful success – Convey clear expectations and information to help others reach desired goals and outcomes – Provide constructive, thorough feedback – Encourage skill development and learning – Support setting of realistic goals |

Competence – Emphasize mistakes – Be overly critical – Highlight failures and faults – Repeatedly give negative feedback – Communicate perceptions of participants’ ineffectiveness and doubt improvements |

Competence – Negligence or inattention towards providing adequate guidance, feedback, and organization to help participants’ feel capable of facing challenges and/or experiencing success |

|

Relatedness – Demonstrate affection, care, and emotional stability – Demonstrate warmth and empathy – Show interest and support |

Relatedness – Demonstrate aversion or dislike of others – Being critical – Being hostile – Exhibit active dislike |

Relatedness – Negligence or inattention towards promoting a sense of connectedness with the participants |

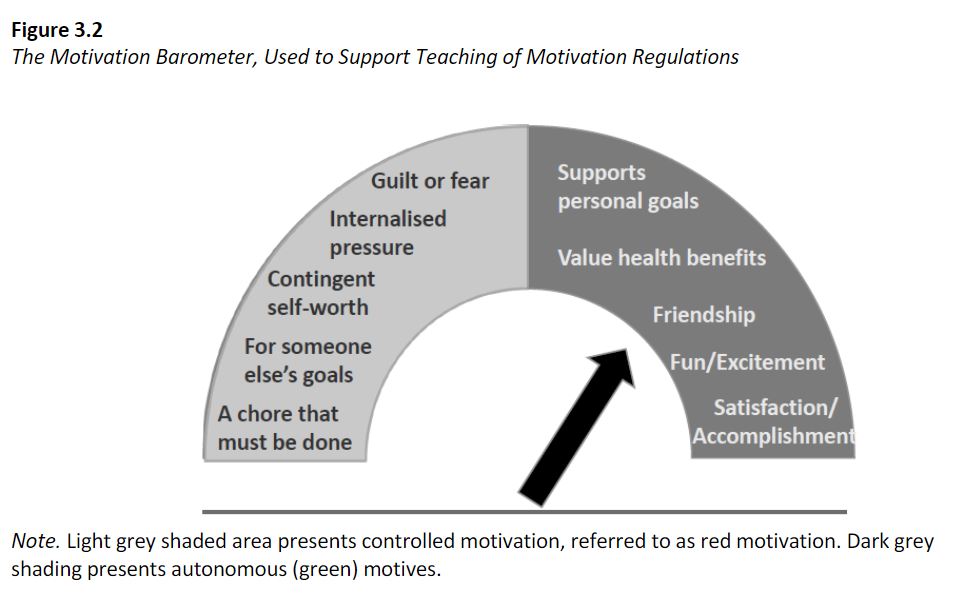

Overview of SDT as Applied in Exercise and Other Physical Activity Contexts

- SDT lends itself well to intervention work, as the theory is explicit about the circumstances under which motivation can be optimized.

- Understanding of motivation as an entity that can range in quality can be helpful for instructors and leaders to understand how their words and behavior can have an impact on the motivation of those they work with

Figure 3.2

Practical Application #1: An Application of Self-Determination Theory in the Context of Group Cycling Exercise Classes

Rationale for the Project

- Despite the widespread popularity of group exercise classes, turnover of attendees is high, with approximately 50% of new attendees dropping out within the first six months.

- The aim of this study was to develop and test a training program for group exercise instructors on how to adopt a motivationally supportive communication style based on the principles of SDT.

Intervention Format and Content

- The training aimed to teach instructors how to maximize their use of motivationally adaptive strategies and minimize their use of motivationally maladaptive strategies during group exercise classes.

- To simplify the presentation of the strategies to the instructors, we grouped the need supportive strategies using the acronym LARS:

- Listening to your participants

- Advising your participants

- Relating to your participants

- Structuring your class

Strategies to Incorporate

The participant instructors were encouraged to try out a couple of the following specific strategies each week:

- Taking time to listen and be responsive to your participants’ needs

- Encouraging questions and feedback from your participants about their goals, problems or preferences

- Giving meaningful and appropriate explanations

- Giving specific and constructive feedback

- Using an inclusive language (e.g., “we could try…”)

- Acknowledging the participants’ feelings and responding appropriately

- Offering meaningful praise which is unconditional

- Create opportunities for participants to have input and make decisions about the workout

- Offering choice and variety which are realistic and relevant to your participants’ needs

- Find opportunities to interact with all participants

Strategies to Avoid

We also explored with the instructors how to avoid using strategies that would be likely to neglect or thwart the basic needs; these strategies were grouped under the acronym PEAS:

- Pressuring language

- Empty communication

- Appearing cold

- Structuring your class

Major Findings

- The training led to increases in perceived use of a more motivationally adaptive communication style by instructors

- The training led to increases in instructor and exerciser need satisfaction but no statistically significant changes in self-determined motivation

- The training program was considered feasible and acceptable to instructors

- Barriers and facilitators to implementing adaptive motivational exercise instruction

Strengths of the Project

- The findings contribute to the existing evidence with regard to the benefits of implementing SDT-based interventions in exercise settings with non-clinical populations.

- This is the first study in the group exercise domain which shows that SDT-based communication training can lead to both increases in perceptions of adaptive instructor behaviors and decreases in instructors’ use of controlling motivation strategies.

- The findings suggest that SDT-based training programs can positively impact exercise instructors’ satisfaction at work, with instructors reporting higher levels of autonomy and relatedness satisfaction.

Limitations of the Study

- With regard to instructors’ and exercisers’ motivational regulations, baseline scores were high (autonomous motivation) or low (controlled motivation and amotivation), leaving little room for improvement, which may explain the lack of significant changes in self-determined motivation.

- There was no objective measure of usage of training material. Usage of videos was self-reported by instructors.

Practical Application #2: Application of Self-Determination Theory in the Context of Group Walking in Retirement Villages

Rationale for the Project

- It has been recommended that older adults engage in at least 150 minutes of physical activity a week, however, the majority of older adults are insufficiently physically active to obtain health benefits and are putting themselves at an increased risk for premature mortality, chronic illness and reliance on health care systems

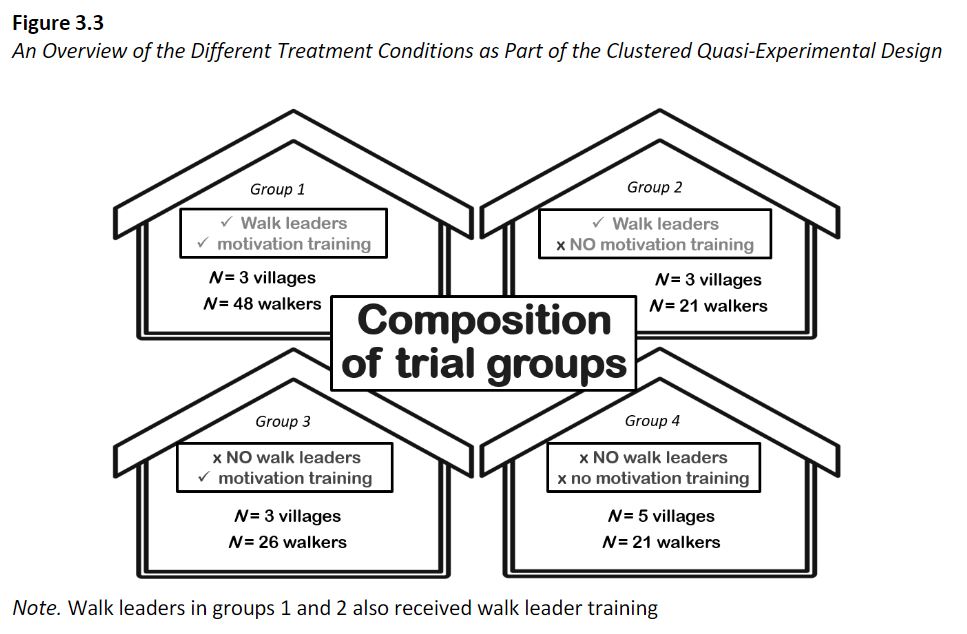

- The aim of the Residents in Action Trial (RiAT) study was to examine the acceptability, feasibility, and implementation of a 16-week peer-led walking intervention that is led by older peer walk leaders, who were trained in need supportive communication strategies.

- The intervention was designed to promote autonomous motivation to be physically active, as a means to increase walking, reduce sitting and improve health and well-being in physically inactive older adults residing in retirement villages in Western Australia.

How the Study was Conducted

- Purposive sampling was used to recruit 116 insufficiently physically active retirement village residents (92% female) who took part as walkers (mean age = 78.37years, SD= 8.30, 92% female), 12 physically active residents who volunteered as walk leaders and three retirement village managers. The trial lasted 16 weeks and was conducted in 14 retirement villages in Western Australia. Each village was allocated to one of four different treatment conditions, which are illustrated in Figure3.3

Figure 3.3

Intervention Format and Content

- Mixed-methods were used to examine the acceptability, implementation, and efficacy of the 16-week walking intervention and factors affecting the effectiveness and persistence as a volunteer walk leader. Data were obtained from accelerometers (ActivPals worn for seven days), questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and participant logbooks. Data were collected at pre-intervention, post-intervention (i.e., immediately after the 16-week intervention) and at a 6-month follow up.

Major Findings

- Walkers led by a motivation-trained leader increased their physical activity but did not improve mental health and well-being

- Walking with others at least once a week was associated with better outcomes as compared to walking alone

- Supportive interactions were perceived as important

- Volunteer motivation, volunteer attributes and need satisfaction determined the persistence and effectiveness of volunteer walk leaders

- Acceptability: Can older peers be recruited as walk leaders and trained in need supportive strategies?

Strengths of the Project

- The study advances existing walk leader and SDT research by being the first to evaluate the feasibility of training older peer walk leaders in need supportive strategies. An important strength of the study is that it provides comprehensive (qualitative and quantitative) understanding on the acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy of using motivation training to help older volunteers become “motivating” walk leaders

- These findings can inform future peer-led intervention designs and how older walk leaders can be selected, trained and supported.

Limitations of the Study

- Limitations include a high number of individuals who self-reported being physically inactive at baseline but who were, in fact, physically active as determined by accelerometer devices. It suggests a need for future researchers to examine additional efficient means of attracting physically inactive older adults to peer-led walking programs.

- In the future, researchers could also examine what are the most effective strategies to recruit and retain walk leader volunteers.

- Finally, interventions could examine the feasibility and effects of smaller groups/walking dyads to address the challenge of dealing with diverse abilities within the same group.

Conclusions and Future Research Directions

- The two studies described in this chapter illustrate how innovative approaches to support motivation can be employed to reap the aforementioned benefits.

- As the world continues to battle the pandemic of physical inactivity, innovative approaches to support motivation, via interventions with peers, instructors, and other social agents, will have a critical role to play.

Learning Exercises

1. What is meant by “quality” motivation, and when is someone more likely to experience it?

2. How does self-determination theory distinguish itself (i.e., what sets this theory apart) from other theories of behavior change covered in the book?

3. Discuss some potential factors, at the personal or contextual level, that might prevent exercise instructors from (fully) using the LARS strategies.

4. Discuss some potential factors, at the personal or contextual level, that might prompt exercise instructors to use the PEAS strategies.

5. How could you adapt the motivational strategies outlined in the chapter to office workers who are insufficiently physically active and living with overweight or obesity, taking into consideration the time constraints they are likely to have?

6. You are being asked to use the motivational strategies outlined in the chapter to lead a walking group of physically inactive, similar aged peers. How could you adapt the strategies to make them relevant to your peer group? What might be challenges when using each of the strategies? What could you do to overcome these challenges?

7.What are some of the challenges that might be faced when doing research to promote more adaptive motivational styles? How might they be overcome?

Glossary terms

- Introjected motivation: Motivation that is underpinned by internal pressures or contingencies, such as fear

- External regulations: Regulations which have no internal driver, and reflect force, pressure or coercion from someone else

- Competence: To feel capable, can meet challenges, efficacious

- Autonomy: Volitional and willingness to take part in the behavior

- Relatedness: To feel respected, cared for and connected to others

- Autonomy need frustration: The feeling that one has been pushed or forced to behave in a certain way.

- Competence need frustration: Feeling useless and hopeless.

- Relatedness need frustration: Feeling disliked, excluded, or deliberately ignored.

- Amotivation: A state in which the individual lacks intention or reason to continue

- Basic need satisfaction: Considered fundamental for people to thrive, not merely survive.

- Competence: To feel capable, can meet challenges, efficacious

- Autonomy: Volitional and willingness to take part in the behavior

- Relatedness: To feel respected, cared for and connected to others

- Need supportive: More likely to experience need satisfaction, which leads to more autonomous motivation for the activity, and in turn, adaptive outcomes.

- Need thwarting: Needs are likely to be frustrated, motivation is likely to be controlled, and maladaptive consequences are predicted to ensue.