Chapter 12: Affective Responses to Exercise: Measurement Considerations for Practicing Professionals

Chapter Overview

Affective Responses to Exercise

Measuring Affective Responses in an Exercise Setting: An Example Vignette

Poor Measurement Technique: A Vignette

Hedonic Theory

Core Affect, Emotion, and Mood

Core Affect

Emotion

Mood

The Measurement of Affective Responses to Exercise

Measure Selection

Timing and Measurement Frequency

Figure 12.1

Figure 12.1

Figure 12.3

Individual Variability

Neutral Measurement by the Exercise Professional

Environmental and Situational Considerations for Reducing Measurement Error

The Measurement of Remembered Pleasure and Forecasted Pleasure

Measuring Affective Responses in an Exercise Setting: An Example Vignette Revisited

Better Measurement Technique

Conclusion and Recommendations for Professional Practice

Learning Exercises

Affective Responses to Exercise: Measurement Considerations for Practicing Professionals

Chapter Overview

- We provide guidance for the measurement of affective responses to exercise for practicing professionals.

- In this chapter, we briefly describe hedonic theory applied to exercise behavior.

- Then we distinguish between the similar, but distinct, psychological constructs of core affect, emotion, and mood before discussing measurement considerations, including measure selection, timing and measurement frequency, individual variability, and the importance of neutral measurement technique.

- Next, we provide guidance for the measurement of remembered pleasure and forecasted pleasure.

- Finally, we present a hypothetical example using improved measurement techniques to illustrate how concepts from this chapter can be applied to a realistic scenario

Affective Responses to Exercise

- Affective responses refer to the pleasure and displeasure that an individual experiences (Ekkekakiset al.,2008).

- An exerciser’s affective responses may fluctuate frequently during exercise, and these changes are motivationally relevant.

- It is, therefore, critical that exercise professionals consider the pleasure experienced during exercise as an essential component of the exercise prescription, in addition to its safety and effectiveness (Ekkekakiset al., 2011; Ladwiget al., 2017).

Measuring Affective Responses in an Exercise Setting: An Example Vignette

- To illustrate a new concept, it may be helpful to begin with an example of what should not be imitated. Here, we present a realistic scenario that should not be recreated.

- Near the end of this chapter, we will present an example of another realistic scenario demonstrating better, evidence-based measurement techniques.

- Our goal is to allow readers to understand not only how to measure affective responses to exercise but why these measurement techniques should be chosen.

- To avoid confusion, let us be clear: The following vignette demonstrates flawed or misguided measurement practices.

Poor Measurement Technique: A Vignette

- Pat walked into the student fitness center, with the excitement of a new semester, and the goal to start an exercise program to improve his health. Pat is 19 years old and has never been a regular exerciser. In fact, Pat perceives the fitness center as if it were an alien planet. Pat meets with his personal trainer, Terry, a senior exercise and sport science major. Terry appears very fit, wearing a tight, sleeveless shirt that reveals his muscularity. In addition to assessing Pat’s health history, cardiorespiratory fitness, and muscular fitness, Terry mentions that he is interested in measuring how Pat feels during exercise.

Terry: We’re going to measure your affective responses to exercise.

Pat: Affective responses? What does that mean?

Terry: We’re going to find out how exercise makes you feel. “Affect” is basically another way of saying your “emotions” or “mood”. Exercise has been shown to make you feel better.

Pat: Sounds interesting…What do you need me to do?

Terry: Before we start, I want you to complete this survey, called the Physical Activity Affect Scale (PAAS; Loxet al., 2000). The PAAS measures how exercise changes your mood and emotions. Then, you will complete an exercise session at a moderate intensity for 20 minutes. After you’re finished, you will complete the PAAS again, and we’ll see how the exercise made you feel.

Pat: Why are we using this scale?

Terry: The PAAS (Lox et al., 2000) has been used to measure affective responses in many other exercise studies, and, just like the name suggests, it is a measure of affective responses to physical activity.

- During the exercise session, a few of Pat’s classmates walked into the fitness center. Some of them noticed he was completing exercise testing, and this made Pat feel uncomfortable, judged, and discouraged. Pat felt anxious about how his body and exercise performance looked to his classmates while he was exercising. After completing the exercise bout, Terry smiled and congratulated Pat for doing a good job before giving him the Physical Activity Affect Scale to complete a second time. To Terry’s surprise, compared to baseline, Pat’s responses indicated less positive affect, more negative affect, less tranquility, and more fatigue following exercise. Terry concluded that the exercise session must have depressed Pat’s mood. Because Pat reported feeling worse after moderate-intensity exercise, Terry concluded that this intensity may not be a good component of an exercise prescription for Pat.

Hedonic Theory

- Hedonic theory posits that affective responses and memories of these responses have motivational value, such that people typically seek to repeat experiences that are pleasant and avoid those that are unpleasant.

- Applied to the context of exercise, hedonic theory suggests that people are more likely to participate in exercise that leads them to experience pleasure and avoid exercise that makes them feel displeasure.

- A systematic review by Rhodes and Kates (2015) showed that the prevailing evidence suggested affective responses during exercise were related to future physical activity, while affective responses measured following exercise were not.

- The most recent evidence suggests that practitioners should be skilled in measuring affective responses during exercise so that they are better able to help their clients or patients discover exercises that are pleasant.

Core Affect, Emotion, and Mood

- Although the terms affect, emotion, and mood are often used interchangeably by both researchers and the public, each represents distinct, but interrelated, psychological constructs (Ekkekakis, 2012, 2013).

- Practitioners should understand and appreciate the distinctions between these constructs to avoid mistakenly confusing them and choosing an inappropriate measurement approach.

Core Affect

- Core affect is a combination of pleasure-displeasure (i.e., affective valence) and how activated, or “worked-up” one feels (Russell, 1980; Russell & Barrett, 1999).

- Core affect is omnipresent, always accessible to consciousness, but nonreflective; this means that one does not need to “think about it” to experience it (Russell, 2009).

- Core affect forms the basic foundation for what we experience as moods and emotions, and it is unlikely that humans would experience these higher-order mental processes without it.

Emotion

- Emotion requires cognitive appraisal, or a subjective interpretation of an environmental stimulus (Lazarus,1982).

- In contrast to core affect, emotions are always about “something” the individual is experiencing, either directly or indirectly. Additionally, emotions are less frequent and more transient, lasting from seconds to minutes (Ekkekakis, 2013).

- Emotions are often complex and involve core affective responses, the cognitive appraisal of a situation or stimulus, bodily changes, vocal and facial expressions, and action tendencies (Davidson, 2003; Ekkekakis, 2012, 2013; Ellsworth, 2009; Lauckner, 2015).

- Examples of emotions include anger, guilt, love, and pride (Ekkekakis, 2013).

Mood

- Moods share much of the same complexity as emotions but are longer lasting and their antecedents can be more ambiguous. In contrast to emotion, individuals often cannot identify precisely what led them to their current mood state (Ekman, 1994).

- The antecedents for moods maybe cumulative or diffuse (Morris, 1992, 1999).

- Examples of moods include irritation, joyfulness, cheerfulness, and grumpiness (Ekkekakis, 2013).

The Measurement of Affective Responses to Exercise

- In the following sections, we focus on several methodological considerations for practitioners seeking to measure affective responses to exercise including measure selection, the timing and frequency of measurement, expected individual variability in affective responses to exercise, reducing measurement bias, and considerations for decreasing measurement error.

Measure Selection

- There are two general approaches to selecting measures to assess affective responses to exercise.

- The first is by far the easiest and involves choosing a measure that “has been used by others before.” However, as is often the case, the easiest approach is not necessarily the best approach.

- Alternatively, Ekkekakis (2012, 2013) outlined a three-step approach to measure selection. The first step involves choosing whether one wants to measure affect, mood, or emotion. In the second step, the exercise professional should choose a conceptual model that is appropriate for the construct identified in the first step. The final step involves choosing a measure based on the adopted conceptual model and psychometric considerations.

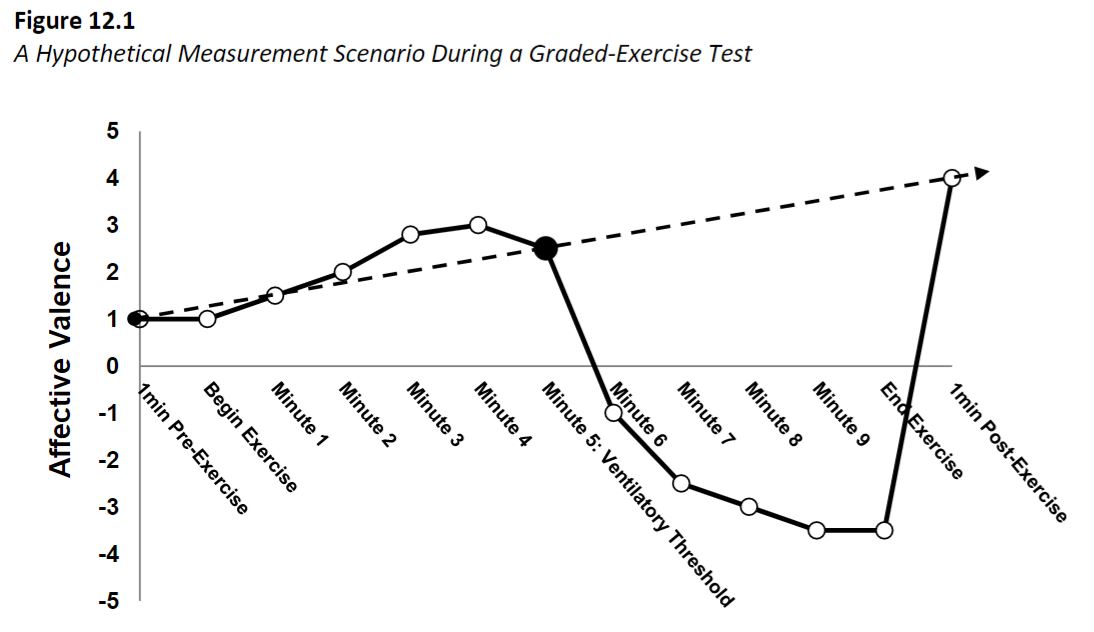

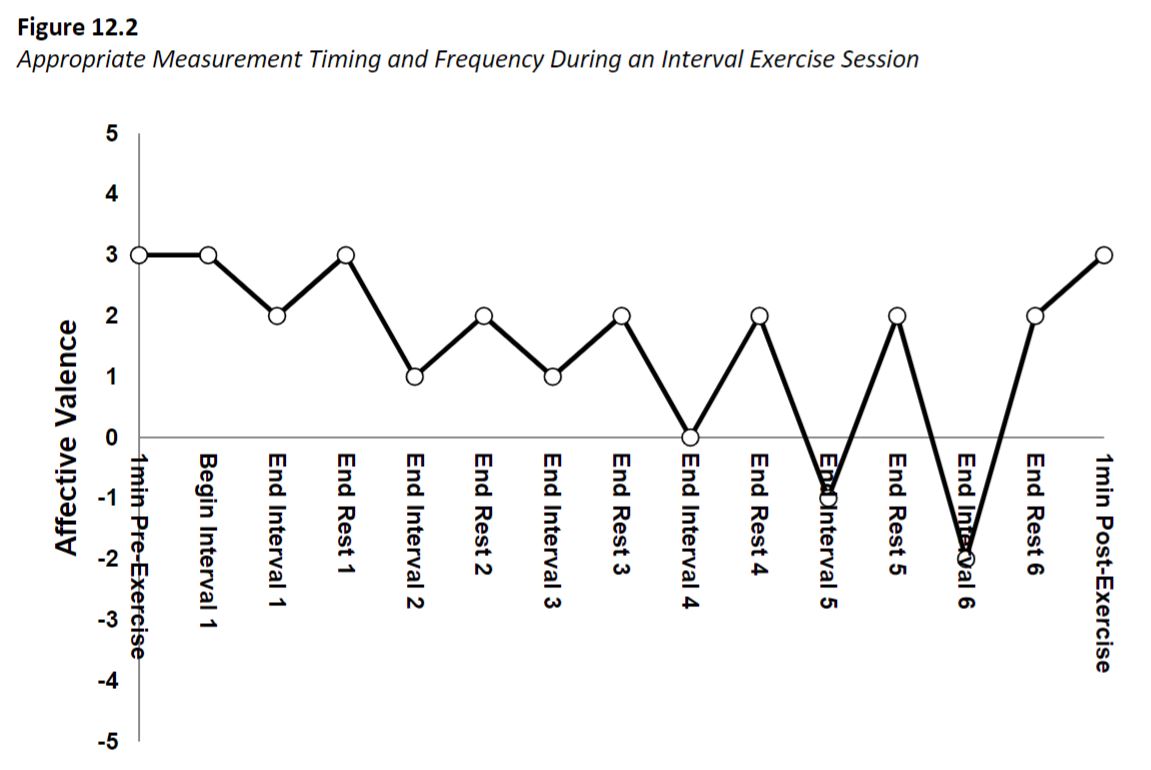

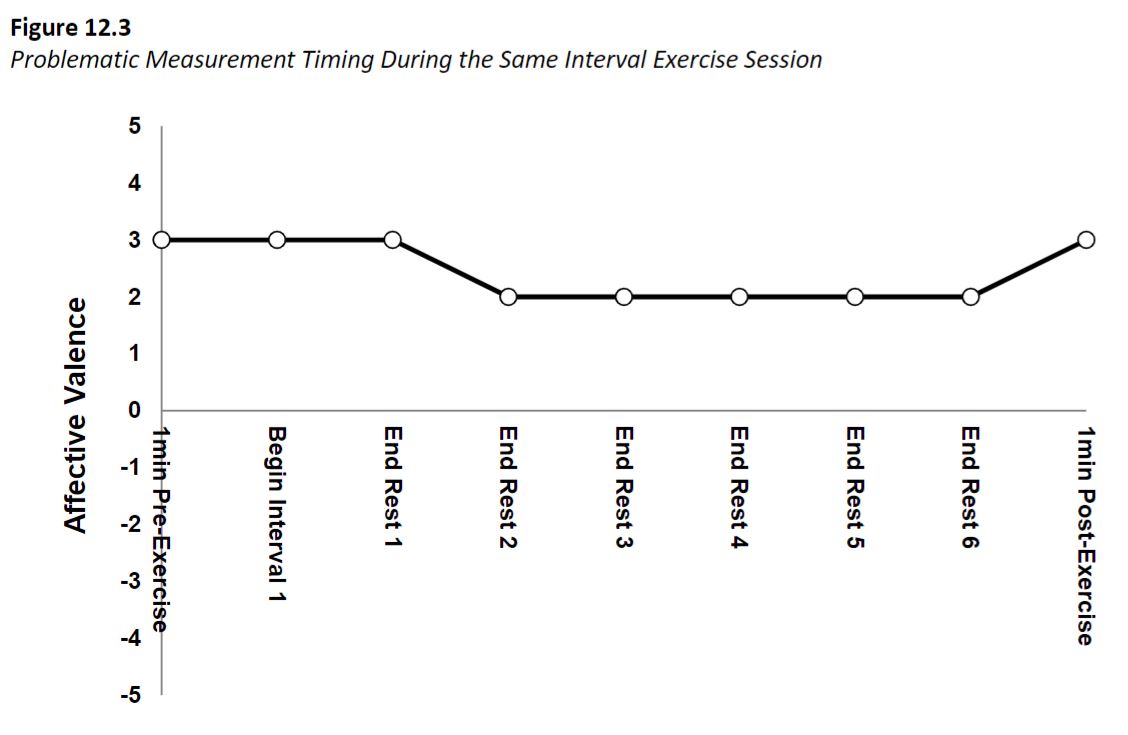

Timing and Measurement Frequency

- The timing and frequency at which exercisers are asked to report their affective responses during exercise can profoundly influence the interpretations of those collecting the measurements.

- To achieve a clearer understanding of the affective responses to exercise of a client, it is recommended that measurement of affective responses occurs frequently before, during, and after exercise.

- Unpleasant affective responses typically rebound following cessation of vigorous-to maximal-intensity intervals (Box et al., 2020). Therefore, to best capture the range of affective responses experienced during the frequent ups-and-downs of interval exercise, exercise professionals should ensure that their measurement timing and frequency also faithfully represents the anticipated patterns of affective responses to interval exercise.

- If measurements of affective responses about the exercise interval are solicited during the subsequent rest interval, the rapid affective rebound effect of resting may bias the interpretation of the affective experience of the client. This would also render the measure as one of remembered pleasure rather than experienced pleasure.

Figure 12.1

Figure 12.2

Figure 12.3

Individual Variability

- Individual variability in affective responses is to be expected, especially around the transition from moderate-to vigorous-intensity.

- For example, in a seminal study by Van Landuyt and colleagues (2000), participants exercised for 30 minutes at moderate exercise intensity. On average, there was no change in pleasure or displeasure during exercise, while activation increased. However, when the researchers examined individual differences in affective responses, they noted that 44.4% of participants felt increasing levels of pleasure during exercise, 14.3% exhibited essentially no change, and 41.3% felt less pleasant.

- These results suggest that it is prudent to analyze changes in affective responses during exercise on both the individual and group level, as opposed to just at the group level.

Neutral Measurement by the Exercise Professional

- The measurement fidelity of exercise affective responses can also be influenced by the person doing the measurement.

- When an exercise professional solicits affective responses from a client, their demeanor can subtly (or sometimes, clearly) bias the affective responses of the client.

- Exercise professionals who wish to collect accurate measures of affective responses to exercise among their clients should do their best to ask questions in a non-leading manner with neutral facial expressions and tone of voice.

- Whichever tone of voice and facial expression the professional adopts should be used consistently throughout exercise so that subtle changes in demeanor do not unduly influence the affective responses of the client

Environmental and Situational Considerations for Reducing Measurement Error

- There are many potential environmental and situational influences on affective responses to exercise; practitioners should be mindful of these influences and aim to assess affective responses in a standardized setting.

- Using standardized instructions for measures, as well as asking whether the concept makes sense to the individual, can help to reduce instances of measurement error.

- Having a distraction, such as music and video, can help to attenuate unpleasant feelings during exercise. For some, if the same exercise intensity is performed without music and video, their exercise affective responses may not be the same as if they were in the presence of the distracting audiovisual stimuli.

- For some individuals, exercising alone, away from mirrors and the prying eyes of others, may improve their affective responses. Similarly, leadership style of exercise leaders in group fitness settings may influence affective responses to exercise (Raedeke et al., 2007).

- Exercise environments that are too hot or cold may also impact how the exerciser feels and should be considered. A hot room may raise body temperature to the point where exercise becomes increasingly uncomfortable.

The Measurement of Remembered Pleasure and Forecasted Pleasure

- It is important to note that remembered pleasure (sometimes called recalled or remembered affect) and forecasted pleasure (sometimes called predicted pleasure) are distinct psychological constructs and use different measurement strategies from those discussed so far.

- Perfect relationships between experienced pleasure, remembered pleasure, and forecasted pleasure are unlikely, even if the exerciser is evaluating the same exercise protocol.

- To measure remembered pleasure, you may consider asking your participant to evaluate their exercise session by responding to the question “How did the exercise session in the laboratory make you feel?” (Zenko et al., 2016). Likewise, forecasted pleasure might be assessed using the question “If you repeated the exercise session again, how do you think it would make you feel?” (Zenko et al., 2016).

- Since memories and predictions are susceptible to biases, it is expected that remembered pleasure of a previous exercise session will not be fully explained by moment-to-moment core affective responses measured during the actual exercise session. Likewise, it is expected that predictions and affective forecasts about future exercise sessions will also be biased and not fully explained by experienced pleasure or remembered pleasure.

Measuring Affective Responses in an Exercise Setting: An Example Vignette Revisited

- The following example highlights evidence-based principles and techniques of the measurement of affective responses to exercise that should be emulated.

- It is important to acknowledge that these are not the only ways to measure affective responses to exercise. Instead, our goal is to demonstrate how to carefully consider measurement choices based on the best evidence currently available.

Better Measurement Technique

- Pat walked into the student fitness center, with the excitement of a new semester, and the goal to start an exercise program to improve his health. Pat is 19 years old and has never been a regular exerciser. In fact, Pat perceives the fitness center as if it were an alien planet. Pat meets with his personal trainer, Terry, a senior exercise and sport science major. Terry wears comfortable exercise attire that does not overly accentuate his figure. In addition to assessing Pat’s health history, cardiorespiratory fitness, and muscular fitness, Terry mentions that he is interested in measuring how Pat feels during exercise.

Terry: We’re going to measure your affective responses to exercise.

Pat: Affective responses? What does that mean?

Terry: We’re going to find out how exercise makes you feel. Specifically, I am interested in core affect, and I will be assessing how the pleasure and displeasure that you experience during exercise changes from moment-to-moment. At some moments, you may feel better, and at other times, you may feel worse.

Pat: This sounds interesting. What do you need me to do?

Terry: I will be administering the Feeling Scale (Hardy & Rejeski, 1989) multiple times, before, during, and after you exercise. This will allow me to have a more comprehensive understanding of your affective experience.

Pat: Why are we using the Feeling Scale (Hardy & Rejeski, 1989)?

Terry: That is a great question. Although there are many potential measures available, I am adopting the conceptualization of core affect proposed by Russell and colleagues (Russell, 1980, Russell & Barrett, 1999). This suggests that core affect is comprised of two distinct dimensions, namely affective valence, which is a bipolar dimension ranging from displeasure to pleasure (Russell & Carroll, 1999), and activation or arousal. Since I am most interested in the pleasure and displeasure that you experience, I will be using a measure that corresponds to this dimension. The measure ranges from very bad to very good and appears to have acceptable psychometric properties in people your age. It also has practical strengths that make it acceptable for our purposes. If I was interested in measuring a distinct mood state, such as your level of depression, I would take an entirely different approach.

- Before Pat begins exercising, Terry reads the standardized instructions of the Feeling Scale to Pat and checks for comprehension. During the exercise session, a few classmates came to the fitness center, and this made Pat feel uncomfortable, judged, and discouraged. Pat felt social-physique anxiety, embarrassment, shame, and guilt when others were present. Terry made note of this observation, and when analyzing Pat’s affective responses, Terry discovered that Pat reported pleasure during exercise until the classmates joined. Thankfully, the multiple assessments of affective valence allowed Terry to identify this pattern. In the presence of classmates, Pat’s showed increasingly unpleasant affective responses. In addition to considering how the exercise stimulus itself made Pat feel, Terry considered the environmental and social context of the exercise session (i.e., exercising in the presence of others). Terry made another appointment with Pat so that his affective responses to exercise could be assessed in a private setting. Terry was careful not to assume that every one of his clients would have a similar pattern of affective responses to exercise. Terry recognized that, unlike Pat, others may thrive and relish the opportunity to “show off” while exercising in front of others.

Conclusion and Recommendations for Professional Practice

- Using this “affect-based” exercise prescription methodology may help new and returning (i.e., those who were once active but have been chronically sedentary) exercisers experience moment-to-moment pleasure as they begin an exercise regimen which may increase the odds of exercise adherence.

- Remember that affective responses are highly variable between individuals.

- Always be cognizant that both the way you present yourself to your clients and the exercise environment can influence how your clients feel.

- Frequently measure the affective responses of your clients and consider modifications based on these data. If you discover a client experiences displeasure during a certain exercise intensity, duration, and/or modality, changes to make the experience more pleasant may be necessary.

Learning Exercises

- What are the differences between affect, mood, and emotion?

- Describe the three-step process of measure selection proposed by Ekkekakis (2012, 2013).

- Imagine that you’re measuring affective responses to exercise. The exerciser is using a treadmill for 30 minutes. When, and how frequently do you measure affective responses? Which measure(s) do you use? Justify your responses.

- It is a common belief that exercise makes people feel better, and this is one of the many benefits of exercise. How would you respond to someone who tells you that “exercise makes people feel better”? Justify your response.

- What are some methods you could use to help make your client feel better during exercise (also see Jones & Zenko, Chapter 11)?

Glossary

- Affective responses: The pleasure and displeasure experienced before, during, and after acute bouts of exercise.

- Core affect: A neurophysiological state that underlies simply feeling good or bad, forms the basic foundation for what we experience as moods and emotions, and, it is unlikely that humans would experience these higher-order mental processes without it.

- Remembered pleasure: A retrospective evaluation about a previous affective experience

- Experienced pleasure: Pleasure experienced at that moment

- Physical Activity Affect Scale (PAAS; Loxet al., 2000): Measures how exercise changes your mood and emotions.

- Hedonic theory: People typically seek to repeat experiences that are pleasant and avoid those that are unpleasant.

- Cognitive appraisal: A subjective interpretation of an environmental stimulus (Lazarus,1982).

- Moods: Contains much of the same complexity as emotions but are longer lasting and their antecedents can be more ambiguous.