Chapter 15: Exercise and Physical Activity for Depression

Chapter Overview

Depression

Prevalence and Burden

How is Depression Diagnosed?

Treatments for Depression

Purpose of the Chapter

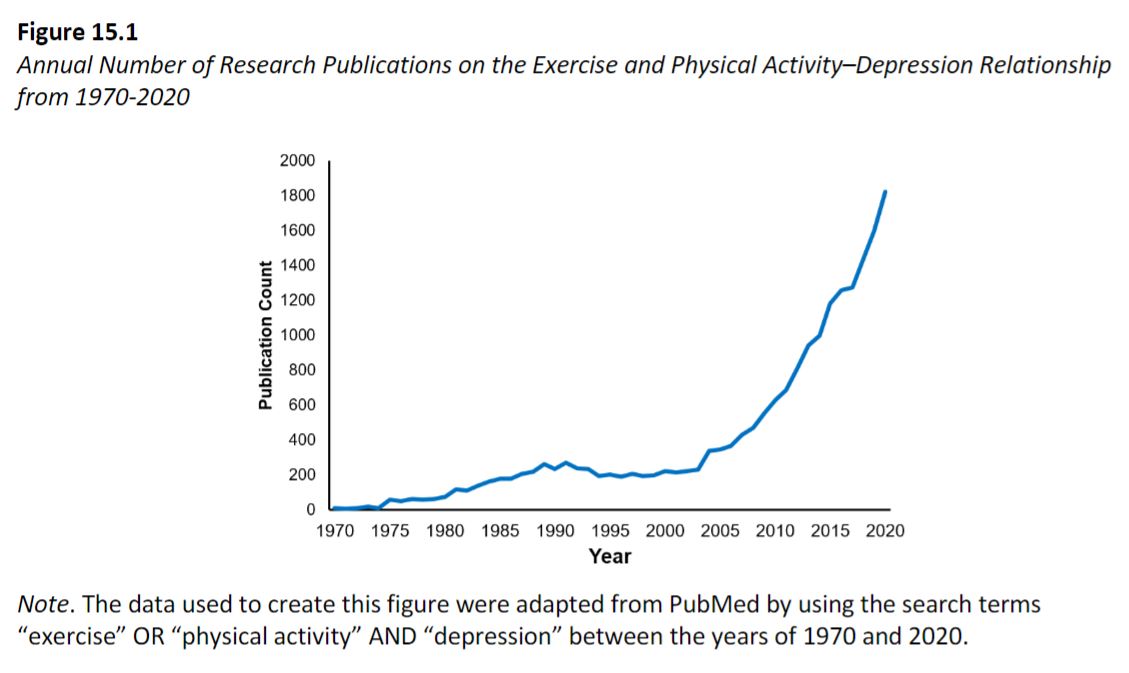

Figure 15.1

Measurement of Major Depressive Disorder and Depressive Symptoms

Diagnostic Interviews

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5)

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)

Dimensional Measures of Depressive Symptoms

Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II)

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD)

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

Exercise and Physical Activity in the Prevention of Depression

Exercise and Physical Activity in the Treatment of Depression

The Role of Acute Exercise in the Treatment of Depression

The Role of Chronic Exercise in the Treatment of Depression

Plausible Neurobiological Mechanisms of the Antidepressant Effect

Neurobiological Mechanisms Studied in the Context of Acute Exercise

Neurobiological Mechanisms Studied in the Context of Chronic Exercise

Conclusion

Learning Exercises

Exercise and Physical Activity for Depression

Chapter Overview

- Depression is a leading cause of global disease burden. Standard treatments include pharmacological and psychotherapy; however, these treatments are not effective for everyone and are associated with several barriers and a substantial side effect profile.

- There is a need to identify alternative approaches that can be used to treat, or even prevent depression.

- Exercise and physical activity are two lifestyle behaviors that have been touted for decades as strategies used in the prevention and treatment of depression.

- The purpose of this chapter is to provide an overview of the scientific evidence supporting the role of these two lifestyle behaviors used in the prevention and treatment of depression.

Depression

Prevalence and Burden

- Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most common mental illnesses, with point estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study indicating a mean global prevalence of 3.6% each year between the years 1990 and 2019 (Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, 2020).

- MDD is a leading cause of disability around the world (Friedrich, 2017) that results in a loss of work productivity and increased morbidity (Cuijpers et al., 2014; Walker et al., 2015).

- MDD is highly recurrent, with about 35% of individuals experiencing an additional MDD episode within the first year of recovery (Hardeveld et al., 2010). Even after 15 years following recovery, up to 85% of individuals experience another MDD episode.

- The total estimated economic burden of people with MDD was $210.5 billion in 2010, with ~$27.7 billion in direct costs due to medical and pharmaceutical services directly related to MDD treatment (Greenberg et al., 2015).

How is Depression Diagnosed?

- Current diagnostic practices rely on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and use specific symptoms as indicators of depression to reach a diagnostic threshold.

- To constitute a DSM-5 MDD diagnosis, an individual must endorse five of nine symptoms that are present for a minimum of 2 weeks and persist for most of the day, nearly every day (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

- Individuals must endorse at least one of two core criterion symptoms: depressed or low mood and/or loss of interest or pleasure in almost all typically or previously enjoyable activities.

- An individual must also endorse at least four other symptoms:

- Significant unintentional change in weight or appetite

- Sleep disturbances (defined as insomnia or hypersomnia)

- Severe psychomotor agitation or retardation observable by others

- Fatigue or low energy

- A sense of worthlessness or excessive guilt

- Impaired ability to think or concentrate and make decisions

- Recurrent thoughts of death that include suicidal ideation and/or attempts.

Treatments for Depression

- Clinical practice guidelines recommend the use of pharmacotherapy, psychotherapeutic approaches, or a combination of the two as first-line treatments for MDD.

- Antidepressant drugs, namely selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), are among the most prescribed medications and work by blocking the reuptake of serotonin. Other classes of antidepressant drugs are also prescribed, all of which work by inhibiting the reuptake of their targeted neurotransmitter(s), thereby increasing its availability, and altering their levels in the brain.

- Research has shown that even among patients who achieve remission using antidepressant drug treatment, long-term outcomes are uncertain, as estimates indicate that approximately 40% of remitted patients are likely to relapse within a two-year period (Boland & Keller, 2008).

- There are several barriers associated with antidepressant drugs including cost and a vast side effect profile, including but not limited to nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dry mouth, constipation, and sexual dysfunction.

- As with antidepressant drugs, psychotherapy is associated with variable success rates, with many individuals often failing to adequately respond or derive antidepressant benefits to psychological treatments (DeRubeis et al., 2005). Moreover, there are several barriers to accessing psychotherapy for many individuals as well.

Purpose of the Chapter

- Given the variable effectiveness and barriers associated with first-line treatments, there is an urgent need to identify alternative strategies or interventions that can be used to treat depression or prevent the occurrence of the disorder altogether.

- Exercise and physical activity are two lifestyle behaviors that have been touted for decades and even centuries in the management and treatment of depression.

- In this chapter, we examine the research evidence related to exercise and physical activity as prevention and treatment strategies used for depression.

Figure 15.1

Measurement of Major Depressive Disorder and Depressive Symptoms

- Measurement of depression is a challenging endeavor because there is no single measure that can account for its complexity.

- MDD diagnoses are made using well-validated clinical interviewing instruments, while depression symptom severity is measured using self-report rating scales.

- Researchers often combine clinical interviews with rating scales to provide insight into the presence and nature of an individual’s depression.

Diagnostic Interviews

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5)

- The SCID-5 is the most widely used structured diagnostic interview for assessing the DSM-5 disorders (First et al., 2015).

- Clinical psychologists and psychiatrists and other trained mental health professionals use the SCID-5 to assess for the presence of lifetime and current depressive disorders and other psychiatric disorders such as anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, substance use disorders, somatic symptom disorders, externalizing disorders, and trauma-and stressor-related disorders.

- Research suggests that the SCID-5 has excellent reliability, sensitivity, and specificity for most of the psychological disorders with high prevalence, even when the clinical interview is conducted over the telephone (Osório et al., 2019).

- Due to its popularity, the SCID-5has been translated into other languages and has been used in a variety of cultures.

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)

- The MINI is a short, structured diagnostic interview developed jointly by clinicians in the U.S. and Europe that follows diagnostic criteria outlined in the International Classifications of Disease and DSM-5 (Sheehan et al., 1997).

- The MINI is typically used in research to reduce the amount of time it takes to assess and diagnose depression.

- Research suggests that the reliability and validity of the MINI is on par with the SCID (Sheehan et al., 1997).

- The MINI can be conducted within 15 minutes and can serve as a short and accurate assessment of psychopathology.

Dimensional Measures of Depressive Symptoms

- Depressive symptoms have been measured using a variety of self-report rating scales.

- Three commonly used rating scales of depressive symptoms include:

- Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II)

- Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD)

- Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

- These rating scales assess current depressive symptoms severity over a specified time interval and aid in determining whether treatments are effective in reducing depressive symptoms.

Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II)

- The BDI-II assesses the presence of depressive symptoms during a two-week period using 21 items scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0-3.

- Higher scores indicate greater severity of depressive symptoms (Beck et al., 1996).

- A score of 13 or higher on the BDI-II is generally an indication of the presence of a depressive disorder and the BDI-II has shown high sensitivity and specificity when utilized as a screening tool (Lasa et al., 2000).

- The BDI-II has shown good internal consistency and validity across different settings and populations (Steer et al., 1999, 2000).

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD)

- The HRSD is a reliable assessment of the severity of depressive symptoms using 17 items scored from 0-4 (Trajković et al., 2011).

- A total score is obtained by summing all the items together.

- The HRSD provides categories that indicate the severity of depressive symptoms based on the total score.

- For example, a total score from 0-7 indicates normal levels of depressive symptoms, 8-16 suggests mild depression, 17-23 suggests moderate depression, and a score ≥ 24 indicates severe depression (Sharp, 2015).

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

- The CES-D was originally developed to assess the number and frequency of depressive symptoms in the general population (Radloff, 1977).

- The CES-D exhibits strong psychometric properties, including high internal consistency and good divergent and convergent validity (Van Dam & Earleywine, 2011).

- The CES-D has also been validated for use in a variety of age groups, including adolescents and young adults (Roberts et al., 1990).

- In 2004, the original CES-D was revised by Eaton et al. to reflect depressive symptoms more accurately as indicated by the DSM.

- The CESD-R is also 20 items, with each item scored on a scale of 0-3. Higher scores reflect greater severity of depressive symptoms.

Exercise and Physical Activity in the Prevention of Depression

- The potential for exercise and physical activity to prevent depression has been studied across a number of cross-sectional and prospective epidemiological studies.

- Gudmundsson and colleagues (2015) examined the relationship between physical activity and depression in a large-scale, prospective study and found a significant relationship between physical activity levels and depressive symptoms, such that decreasing physical activity levels were associated with increased depressive symptoms over time.

- Choi et al. (2019) extracted physical activity and depression data from the U.K. Biobank Study to examine relationships between physical activity and depression and found physical activity may offer protection against the development of depression and symptoms of depression.

- Overall, the available evidence indicates that physical activity and exercise are effective strategies for preventing depression. Although some research suggests that the relationship may be bidirectional (e.g., Gudmundsson et al., 2015), the study by Choi and colleagues (2019) indicates that there may be more robust evidence supporting the preventive role of physical activity on depression.

Exercise and Physical Activity in the Treatment of Depression

- In the following sections, we outline the evidence examining exercise as a treatment for depression and document the potential utility for exercise to be used either as a stand-alone or complementary intervention to existing depression treatments.

- To date, research has examined the effects of exercise on depression using short term (acute) and long term (chronic) interventions.

- Acute interventions have focused primarily on providing short term relief of specific symptoms, such as elevating low mood.

- Chronic interventions have assessed whether exercise can be used to effectively treat or resolve depression (i.e., the disorder) and reduce total depressive symptom severity.

The Role of Acute Exercise in the Treatment of Depression

- Acute (single bouts) exercise will not necessarily resolve an individual’s depressive symptoms, but it has well-characterized effects on regulating mood and has the potential to manage symptoms associated with depression.

- The utility of acute exercise in the treatment of depression may be most evident in the management of symptoms and psychological processes commonly disrupted in depression.

- Acute exercise may be most effective in managing symptoms of depression while other treatments and their effects can manifest, which can take weeks to months (e.g., Knubben et al., 2007; Legrand & Neff, 2016).

- Acute exercise has shown to exert powerful effects on mood and other disrupted psychological processes in depression, which may have implications for using exercise as a strategy to help alleviate or manage symptoms (e.g., low mood or deficits in positive or negative affect) in the short run.

The Role of Chronic Exercise in the Treatment of Depression

- There is a long history of research examining the effects of chronic (longer-term) exercise on depression.

- Treatment studies have shown that aerobic and resistance forms of exercise training result in moderate-to-large effect sizes in depressive symptom reduction (Gordon et al., 2018; Schuch, Vancampfort, et al., 2016).

- The antidepressant effects of exercise are at least as comparable to antidepressant drug treatments and there is evidence to suggest that long-term exercise may result in more favorable reductions in depressive symptoms and disorders compared to antidepressant drugs (Babyak et al., 2000)

Plausible Neurobiological Mechanisms of the Antidepressant Effect

- Research attempting to explain the mechanistic effects of exercise on depression often struggle to accommodate for the diverse symptom profiles and presentations across individuals, which makes it difficult to design studies aimed at establishing the mechanisms implicated in the antidepressant effects of exercise; In addition to the heterogeneity, exercise is associated with a wide range of neurobiological effects.

- When considering these factors, it is unsurprising that our general understanding of the mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of exercise is unclear.

- This section provides a brief overview of some of the neurobiological mechanisms that have been assessed in acute and chronic exercise studies.

- The focus is solely on neurobiological mechanisms that are hypothesized to be implicated in the pathophysiology of depression and have been studied in relation to changes in depressed mood or depressive symptoms.

Neurobiological Mechanisms Studied in the Context of Acute Exercise

- Establishing neurobiological mechanisms of the antidepressant effects of exercise has been challenging due to the heterogeneous nature of depression and the wide range of neurobiological effects of exercise, but several mechanisms have been proposed and tested.

- There may be a role of specific oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in the antidepressant effects of exercise training. Overall, the available data for neurobiological mechanisms of the antidepressant effects are too premature to make any definitive conclusions.

Neurobiological Mechanisms Studied in the Context of Chronic Exercise

- Chronic exercise studies have examined potential neurobiological mechanisms associated with the antidepressant effects of exercise. These studies have focused on assessing whether changes in specific neurobiological mechanisms are associated with depressive symptom change in response to exercise treatment.

- To date, chronic exercise studies have focused mostly on oxidative stress markers, BDNF, and inflammatory markers.

- In Schuch et al. (2014), the authors conducted a RCT evaluating the effects of exercise as an add-on treatment to treatment-as-usual on thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) and BDNF among 26 severely depressed inpatients. Serum TBARS levels increased for the exercise group, while no effects were found for serum BDNF levels, indicating that TBARS may be a potential neurobiological mechanism implicated in the antidepressant effects of exercise for participants with depression. It was unclear from this study whether change in TBARS was associated with changes in depressive symptom improvements.

- Lavebratt and colleagues (2017) examined whether serum IL-6 levels could be altered by 12 weeks of exercise and whether changes corresponded to changes in depressive symptoms and found reductions in IL-6 levels were associated with depressive symptom reductions, indicating that IL-6 may be a potential mechanism of the antidepressant effects of a chronic exercise training program.

Conclusion

- MDD is a prevalent and burdensome mental illness that significantly impacts individuals of all age groups across the globe. Antidepressant drugs and psychotherapeutic approaches are first-line treatments for MDD; however, these treatments are associated with several barriers, have variable effectiveness, and have vast side effect profiles.

- Exercise and physical activity are two lifestyle behaviors that can be used to effectively prevent and treat depression; cross-sectional and longitudinal research indicates that engaging in regular physical activity is associated with a diminished risk of current and future depression.

- Even engaging in small amounts of physical activity can reduce an individual’s risk for depression. A large body of evidence has examined exercise programs in the treatment of depression.

- In conclusion, research suggests that consistent physical activity can reduce the risk of developing depression and acute and chronic exercise treatment programs are efficacious in improving mood and symptoms of depression.

Learning Exercises

- Clinicians issue a diagnosis of MDD based on the presence of at least five symptoms that are present over the same two-week time period. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) of the American Psychiatric Association (2013), which two symptoms are required for a diagnosis? Do both symptoms need to be present in order to be issued a diagnosis? Identify the remaining symptoms that may also be present to constitute a MDD diagnosis.

- Can physical activity be useful in protecting against the development of depression or does depression reduce physical activity levels? What evidence is there to support your answer?

- Can exercise be used to treat depression? What evidence is there to support your answer?

- How does exercise compare with antidepressant drugs in the treatment of depression? What are the long-term depression outcomes of either treatment?

- Does a specific dose of exercise elicit larger antidepressant effects compared to other doses of exercise? Use the available evidence to support your answer.

- Most treatment studies examining the effects of exercise on depression have focused on aerobic forms of exercise. Does resistance exercise have utility in the treatment of depression? Use evidence to support your answer.

- Several neurobiological mechanisms have been proposed to underlie the antidepressant effects of exercise. Identify at least two mechanisms that change in response to exercise. Indicate the dosage of exercise that was used in terms of type, frequency, intensity, and duration.

- A friend of yours knows that you are taking a class in sport and exercise psychology. They have recently been issued a MDD diagnosis and are currently considering different treatment options. Your friend wants you to share your insights on how to manage and alleviate their depression. Based on the evidence outlined in this chapter, provide insight into different treatment options in terms of treatment outcomes and efficacy in reducing depression over the long-term. Which treatment would you recommend?

- What type of exercise can individuals do in the short-term versus long-term to manage and reduce their depression? Use scientific evidence to support your answer.

Glossary terms

- CESD-R: Center for Epidemiologic Depression Scale Revised (Eaton et al., 2004).

- Acute: Short-term

- Chronic: Long-term

- BATD: Brief behavioral activation treatment for depression

- RPE: Rating of perceived exertion

- MDD: Major depressive disorder

- SNRIs: Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

- NDRI: Norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors

- SSRIs: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- CBT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy

- Dose-response relationship: The relationship between the amount of exposure to a substance or treatment and the resulting changes in body function or health.