Chapter 16: Physical Activity and Exercise for the Prevention and Management of Anxiety

Chapter Overview

Physical Activity and Anxiety

Can Physical Activity Protect Against Incident Anxiety?

Exercise as a Treatment for Anxiety

Acute Bouts of Exercise for Managing Symptoms

Exercise Training for Managing Symptoms

Exercise Prescription

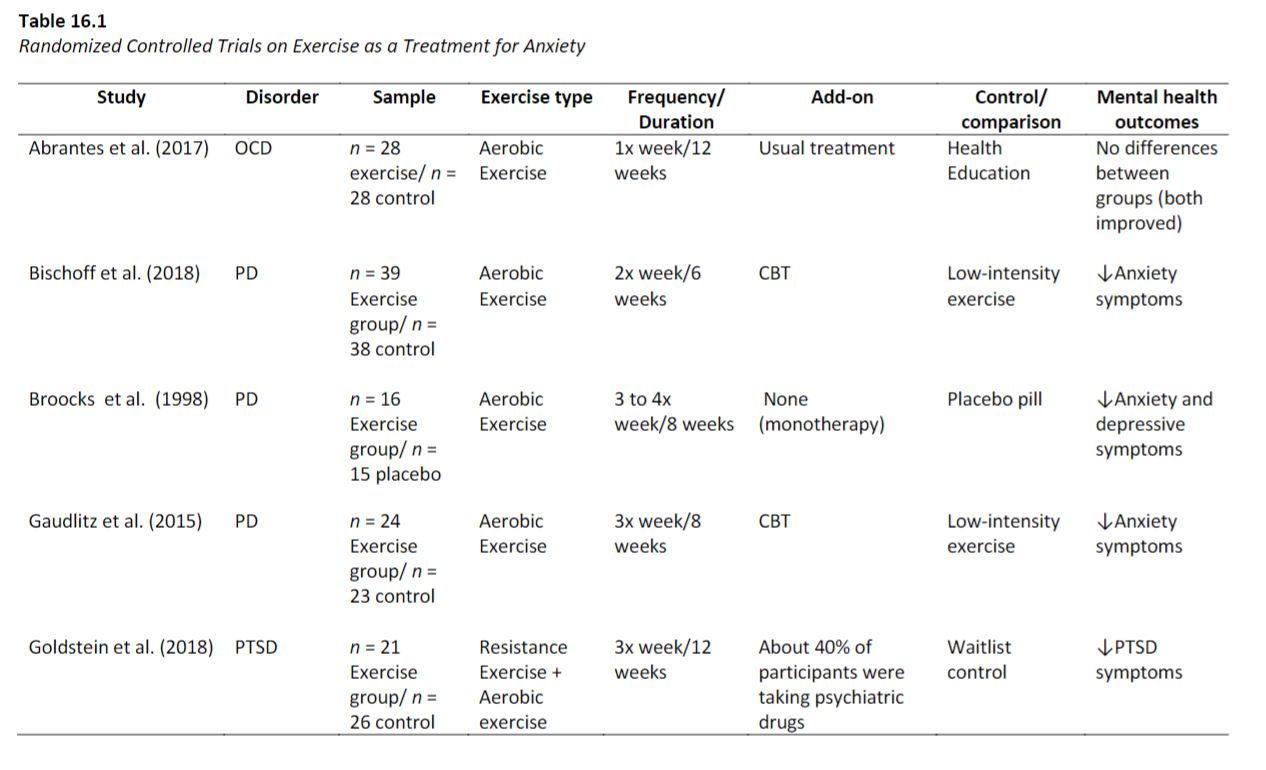

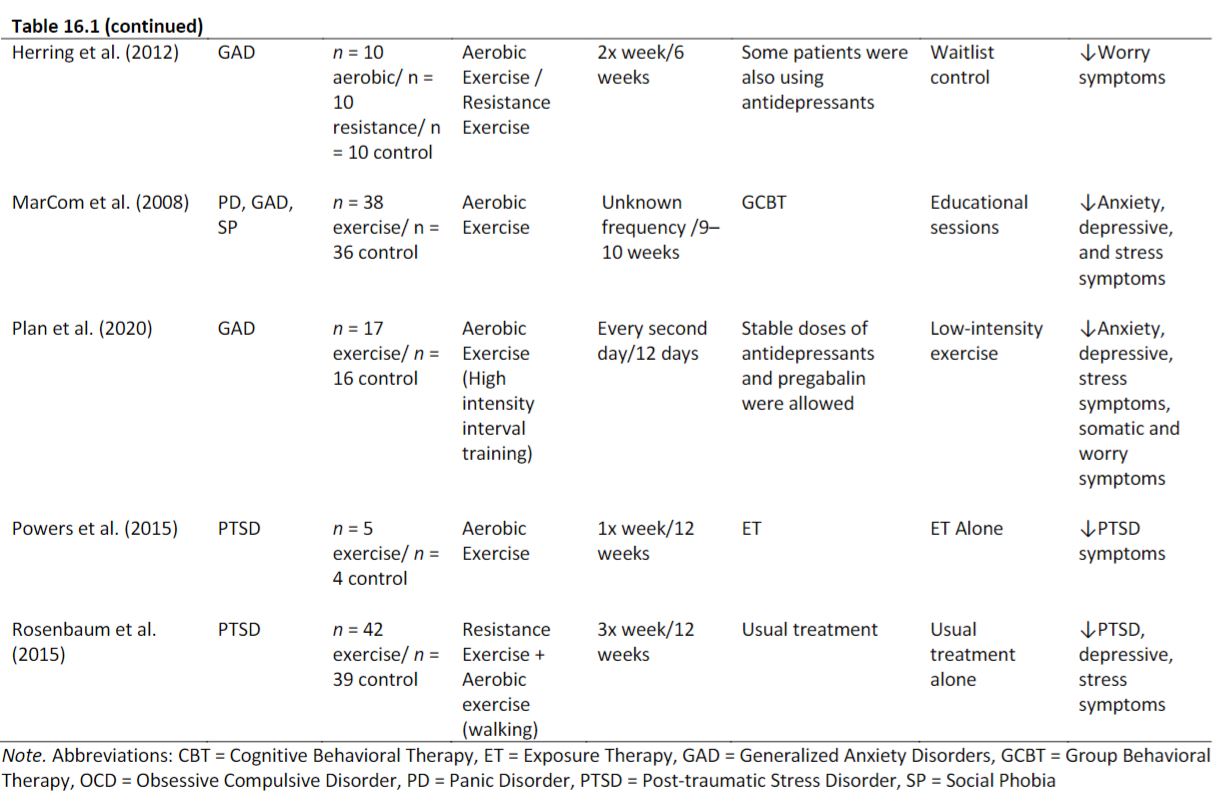

Table 16.1

Potential Mediators (Mechanisms) of the Anxiolytic Effects of Exercise

Conclusions

Learning Exercises

Physical Activity and Exercise for the Prevention and Management of Anxiety

Chapter Overview

- Anxiety disorders are a leading cause of the global disability burden.

- The core features of anxiety disorders include persistent, intense, and excessive fear or worry (American Psychiatric Association [APA] 2013; WHO, 1992).

- The mainstays of treatment for anxiety disorders are pharmacological and psychological interventions.

- Although a growing number of pharmacological treatments are available, about the half of patients do not respond adequately and require additional approaches for the prevention and treatment of anxiety disorders.

- In the present chapter, we provide an overview of the use of physical activity and exercise for the prevention and treatment of anxiety.

Physical Activity and Anxiety

- Given the considerable individual and societal burden of anxiety disorders, there is an urgent need to identify modifiable risk factors and additional intervention strategies to mitigate this burden.

- Emerging evidence indicates physical activity (PA) and exercise can reduce the risk of developing anxiety disorders and be useful strategies for the treatment of anxiety disorders by reducing anxiety symptoms.

- In the present chapter, we provide a brief overview of the current evidence for (a) the role of PA and exercise as protective factors against incident anxiety, and (b) the use of PA and exercise as therapeutic strategies for people with anxiety disorders.

- We highlight the use of exercise as a strategy for acute management of symptoms, the effects of different types of exercise training, neurobiological mediators between exercise and anxiety, and issues related to exercise prescription, adherence, and dropout.

Can Physical Activity Protect Against Incident Anxiety?

- Observational studies have demonstrated that physical activity is associated with a lower risk of incident anxiety at a population level.

- However, the evidence that PA protects against anxiety is mostly based on self-reported questionnaires that are more likely to suffer from social desirability and recall bias (Schuch et al., 2019).

- More recently, some evidence has shown that people with low cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular strength, two objectively assessed measures of physical capacity largely influenced by PA levels, have 60% higher risk (95% CI 1.14–2.11) of presenting anxiety compared to those with higher cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular strength (Kandola et al., 2020).

Exercise as a Treatment for Anxiety

- Randomized controlled trials have found that exercise, a subset of physical activity, can reduce anxiety and stress symptoms in people with anxiety disorders.

- The effects of exercise on anxiety symptoms can be both acute, following a single bout of exercise, as well as chronic, following a period of weeks of intervention.

Acute Bouts of Exercise for Managing Symptoms

- Current evidence has demonstrated that a single exercise bout results in a small reduction in state anxiety (Ensari et al., 2015).

- In the 1970s, some believed that exercise would elicit increased anxiety symptoms in those prone to anxiety attacks/panic episodes (O’Connor et al., 2000). This fear seems to have been borne from an experiment conducted by Pitts and McClure (1967), who demonstrated that the infusion of sodium lactate induced symptoms of anxiety in people with anxiety neurosis. The increase in lactate levels caused by exercise was thought to trigger panic attacks.

- Further evidence has demonstrated that exercise is not only safe for people with panic disorders but also helps to alleviate acute state anxiety symptoms (Ströhle et al., 2009).

Exercise Training for Managing Symptoms

- Diverse studies have attempted to discuss and meta-analytically synthesize the evidence on the anxiolytic effects of exercise training in healthy people (Conn, 2010), people with multiple chronic conditions (Herring et al., 2010), and people with anxiety disorders or elevated anxiety symptoms (Aylett et al., 2018; Bartley et al., 2013; Jayakody et al., 2014; Stubbs et al., 2017). Overall, small effects were observed for people with and without chronic health conditions (Conn, 2010; Herring et al., 2010).

- For people with anxiety disorders or elevated anxiety, there was some divergence in the magnitude and direction of the effects. This can potentially mean that exercise may be more effective for some anxiety disorders compared to others.

- Bartley et al. (2013) synthesized data from seven randomized controlled trials and found no effect of exercise in people with anxiety disorders. However, this meta-analysis included studies comparing exercise versus relaxation plus paroxetine (Wedekind et al., 2010), strength exercises (Martinsen et al., 1989), or cognitive behavioral therapy (Hovland et al., 2013). The inclusion of such studies in a meta-analysis is problematic because the control group “interventions” are largely effective.

Exercise Prescription

- The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommends the use of the frequency, intensity, time, and type (FITT) principle as a strategy to guide the exercise prescription (American College of Sports Medicine, 2013)

- The optimal dose of exercise intensity, frequency, or volume remains unclear. Most randomized controlled trials investigating this topic have shown the effectiveness of moderate-intensity exercise (Stubbs, Vancampfort, et al., 2017).

- In order to maximize exercise engagement and reduce dropout, clinicians and exercise professionals should consider that exercise should be rewarding and enjoyable, and autonomous motivation seems to be a key element for exercise engagement and maintenance (Vancampfort et al., 2015).

- Including the exerciser in the decision-making process should increase the sense of autonomy (Vancampfort et al., 2015).

Table 16.1

Potential Mediators (Mechanisms) of the Anxiolytic Effects of Exercise

- Potential mechanisms underpinning the anxiolytic effects of exercise may be related to changes in biological markers and psychosocial/behavioral factors. Some biological markers are candidates to explain the effects of exercise.

- It is believed that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) potentially counteracts the impact of stress hormones on the hippocampus (Suliman et al., 2013). However, this protective mechanism seems to be impaired in people with anxiety, given that BDNF levels are reduced in this group (Carbone & Handa, 2013). Exercise, in turn, releases the secretion of BDNF in humans (Szuhany et al., 2015).

- One potential psychosocial mechanism relates to anxiety sensitivity. The systematic and deliberate exposure to somatic symptoms, such as increased heart rate, respiratory frequency, and sweating through exercise, has been shown to reduce the fear of bodily sensations related to anxiety (Smits et al., 2008)

- The mechanisms underlying the anxiolytic effects of exercise are not fully understood, but some neurobiological factors, such as changes on neurogenesis, inflammation, endocannabinoids, and regulation of the autonomic system, are potential candidates. In addition, psychological factors, such as reduction of anxiety sensitivity, increases in self-esteem, and mastery may help to explain this effect.

Conclusions

- PA can reduce the risk of anxiety symptoms and disorders in the general population.

- In addition, among people with anxiety, acute and repeated exercise is safe and can alleviate symptoms.

- Exercise also has cardiovascular and metabolic benefits that may reduce the physical health risks that are associated with anxiety disorders.

- The mechanisms related to the anxiolytic effects of exercise are not fully understood but likely include both neurobiological and psychosocial factors.

- Exercise prescription should consider the participant’s motivations, expectations, barriers, and preferences to promote autonomous motivation and long-term adherence.

Learning Exercises

- Is physical activity associated with a reduced risk of incident anxiety? What is the magnitude of the effect?

- Does exercise induce panic attacks?

- Can exercise be used as a complementary treatment for anxiety disorders?

- Explain how exercise could reduce anxiety.

Glossary terms

- Incident anxiety: The occurrence or development of new cases of anxiety.

- Anxiolytic: Used to reduce anxiety.

- FITT: Frequency, intensity, time, and type

- Autonomous motivation: Engaging in a behavior because it is perceived to be consistent with intrinsic goals or outcomes and emanates from the self.

- Ventilatory threshold: The point where oxygen delivery to the muscles becomes a limiting factor, and your body is forced to rely more upon its anaerobic energy system.

- BDNF: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- Autonomic system (AS): A component of the peripheral nervous system that regulates involuntary physiologic processes including heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, digestion, and sexual arousal. It contains three anatomically distinct divisions: sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric.

- Endocannabinoid: The endocannabinoid system (ECS) is a widespread neuromodulatory system that plays important roles in central nervous system (CNS) development, synaptic plasticity, and the response to endogenous and environmental insults.

- Anandamide peripheral: An endocannabinoid in women with major depressive disorder