Chapter 5: Predictors and Correlates of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior

Chapter Overview

Why Predict Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior?

Approaches to Predicting

What Counts as Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior?

Figure 5.1

Predicting Physical Activity

Theory of Planned Behavior

Social-Cognitive Theory

Considerations for Social-Cognitive Theories

Self-Determination Theory

Considerations for Self-Determination Theory

Dual-Process Models of Behavior

Considerations for Dual-Process Models of Behavior

Predicting Sedentary Behavior

Ecological Model of Four Domains of Sedentary Behavior

Correlates of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior

Personal

Social

Environmental

Considerations for Studying Correlates

Conclusion

Learning Exercises

Predictors and Correlates of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior

Chapter Overview

- This chapter is organized by introducing readers to:

- Why predicting physical activity and sedentary behavior is an important research enterprise and adds value to society

- Understanding what constitutes a psychological predictor from multiple levels of complexity

- Issues to consider for the future

Why Predict Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior?

- Researchers want to predict physical activity and sedentary behavior to better explain what makes people behave in ways that would improve their quality of life.

- When viewing physical activity as a preventative strategy, getting enough physical activity can help prevent 6% to 10% of major non-communicable diseases and save millions of lives per year.

- Physical activity is also beneficial for improving brain health and performance.

- The health promotion, disease prevention, therapeutic benefits, and positive psychological effects of physical activity provide substantive justifications for the reason why predicting physical activity is important.

Approaches to Predicting

- Predicting physical activity and sedentary behavior relies on two approaches: explaining what factors cause people to behave and what factors are associated with behavior.

- The first approach often identifies these factors as determinants of physical activity and sedentary behavior. The overarching goal with the explanation approach is to effectively explain how and why people behave.

- The second approach tries to accurately as possible predict behavior and is not necessarily interested in cause and effect or theory to specify what factors lead to behavior. This approach often identifies these factors as correlates of physical activity and sedentary behavior.

What Counts as Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior?

- Physical activity is any bodily movement produced by the skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure.

- Sedentary behavior is any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure ≤1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs), while in a sitting, reclining, or lying posture.

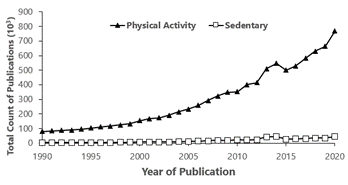

- Although the research on the predictors of sedentary behavior is rapidly increasing, predictors of physical activity dominate the extant literature basPredicting Physical Activity

- Theories are useful to select factors that can explain physical activity behavior.

- The social-cognitive category contains theories that view behavior as a function the beliefs and thoughts of people.

- The humanistic or organismic category views behavior as a function of the innate needs of people to grow, develop, and effectively interact with their environment.

- The third category adds that behavior is a function of both reflective (similar to those of social-cognitive theory) and automatic processes. Automatic processes are rapid and more difficult to be aware of than slower, reflective, more conscious processes.

Figure 5.1

Number of Publications Containing “Physical Activity” vs. “Sedentary”

Predicting Physical Activity

Theory of Planned Behavior

- Intention is the most proximal predictor of physical activity according to the Theory of Planned Behavior.

- Intentions are influenced by three predictors: attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control

- Interventions focus on changing the attitudes, subjective norms, or perceptions of control of people to produce stronger intentions to be physically active. Research findings show that even though interventions that can change the intentions of people, this does not always lead to changes in behavior.

Social-Cognitive Theory

- A key factor of social-cognitive theory that predicts behavior is self-efficacy. This theory supports the idea that the more confident people are in their abilities, the more likely they will be physically active.

- Individuals develop their physical activity efficacy beliefs from four primary sources,

- Past performance accomplishments

- Social persuasion

- Vicarious experiences, and

- Interpretation of physiological and affective states

- Interventions based on social-cognitive theory should emphasize past mastery experiences to develop self-efficacy. Additionally, interventions can focus on social persuasion through feedback and reinforcement, and vicarious experiences to positively influence self-efficacy beliefs towards physical activity.

Considerations for Social-Cognitive Theories

- The definition and measurement of intentions vary across studies despite being an important predictor of behavior.

- There exist two distinct concepts of intention:

- decisional intention—decisional direction to enact the behavior or not, and

- intention strength—intensity of commitment to enact behavior.

- Intention strength appears to be a better predictor of behavior whereas decisional intentions allow for closer examination of factors leading up to decisions and factors that follow decisions.

- Despite the relevance of importance of factors in the theory of planned behavior, it has shown limited predictive validity. This means there are additional factors outside of those used in social-cognitive theories that could enhance the explanation of physical activity behavior.

- This chapter introduces the sources of self-efficacy, but readers should be aware that there are more sources of self-efficacy that may contribute to a person’s situation specific self-confidence.

Self-Determination Theory

- The basis of self-determination theory is that people are growth-oriented organisms that behave in ways to grow and develop their skills.

- Self-determination theory focuses on three broad types of motivation that occur along a continuum of self-determined behavior: Self-determined motivation, Controlled motivation, and amotivation.

- For an individual to be optimally motivated, they must perceive fulfillment of three basic needs in a given context: The need for autonomy, the need for competence, and the need for relatedness

- The degree to which these needs are perceived to be fulfilled impacts self-determined motivation of individuals

Considerations for Self-Determination Theory

- There exist a few challenges with self-determination theory despite its widespread adoption in sport and exercise psychology.

- One challenge is whether the three basic needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness are a complete conceptualization of the needs necessary to influence motivation- Preliminary evidence has identified the need for novelty as an additional basic psychological need.

- Another consideration for self-determination theory is whether individual characteristics make people sensitive to need fulfillment.

- Studying this multilevel influence within and across social complexity may inform researchers and practitioners which individuals may be most receptive to behaviors that fulfill basic needs.

Dual-Process Models of Behavior

- Dual-process models provide a framework for how two systems influence behavior.

- The first system is reflective that uses explicit processes through deliberate thought and conscious awareness to influence behavior. Social-cognitive theories fit within this system to study physical activity behavior.

- The second system is reflexive, concerned with sometimes nonconscious, automatic and implicit processes that influence behavior.

- Such reflexive processes are less studied in physical activity. They may also be best positioned to study sedentary behavior as decisions to be sedentary are less likely to require as much deliberate thought and planning (i.e., reflective processes) as physical activity.

Considerations for Dual-Process Models of Behavior

- Issues related to inconsistent terminology among reflexive processes and how to measure these processes represent current limitations of dual-process research

- Results have shown that only three of the nine measures show acceptable reliability and only the approach-avoidance task demonstrated validity, showing significant correlations with self-reported exercise behavior, and situated decisions toward exercise.

- As this line of research progresses, standardizing the terminology and refining measurement will help research progress and extend understanding of reflexive processes.

Predicting Sedentary Behavior

Ecological Model of Four Domains of Sedentary Behavior

- Ecological models help to provide a framework that shows multiple levels of influence on behavior. They are useful to highlight specific contexts or situations in which factors may be most likely to influence human behavior.

- Ecological models typically organize the levels along intrapersonal, interpersonal, contextual, environmental, and policy levels.

- The ecological model of four domains of sedentary behavior focuses on factors associated with sedentary behavior among domestic, occupation, transport, and leisure.

Correlates of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior

- Researchers study the correlates of physical activity and sedentary behavior to improve understanding.

- Some of these correlates may be sensitive to intervention or change, such as perceptions of time or outcome expectations.

- Other correlates may help researchers identify demographic or individual characteristics that may be risk factors for low physical activity or high sedentary behavior.

- Researchers generally organize these factors into personal, social, or environmental categories

Personal

- Personal-level correlates refer to factors within the individual such as behaviors, perceptions, beliefs, motivations, demographic characteristics, and biological or genetic factors.

Social

- Social correlates include actual and perceived aspects of relationships with other people such as parents, siblings, peers, coaches/teachers, partners, or group members.

- Parental encouragement and parental social support are positively associated with physical activity for young people. Aspects of sibling relationships for youth appear to also correlate with physical activity behavior positively.

- Outside of the family context, aspects of peer relationships such as peer acceptance, friendship quality, support, and modeling are associated with physical activity. Other important social relationships correlated with physical activity include coaches, trainers, partners, and group members.

- Along with social support, being physically active in groups that emphasized group cohesion and group-dynamics was more effective at getting participants to adhere to exercise interventions than exercising alone

Environmental

- The environmental correlates of physical activity and sedentary behavior are characterized by aspects of the context and location.

- Walkability, access or proximity to recreation facilities, and other characteristics of the built-environment are among the most consistent correlates related to physical activity for children, whereas land-use mix, and residential density are most consistent for adolescents.

- For adults, walkability and location of recreational facilities were consistent correlates of physical activity with no clear environmental correlates found for older adults.

- Another aspect of the environment that can influence physical activity and sedentary behavior is weather. Physical activity also appears to vary with changes in seasons.

Considerations for Studying Correlates

- Studying the factors associated with physical activity and sedentary behavior will benefit from moving beyond cross-sectional research designs (i.e., one point in time) to studying how the association changes over time.

- Longitudinal designs can help demonstrate a richer understanding of how associations change or remain stable over time.

Conclusion

- Physical inactivity and increased sedentary behavior are global problems that will require innovation along the science to practice continuum.

- Researchers should be aware that there are numerous factors that can influence human behavior.

- Those interested in better understanding physical activity and sedentary behavior are best positioned when carefully selecting predictors supported by scientific evidence and demonstrated efficacy to change behavior.

Learning Exercises

- What is the difference between the two approaches to studying prediction?

- Why is there more of an abundance of research on predictors of physical activity than predictors of sedentary behavior?

- In what ways can someone design an intervention to increase the strength of physical activity intentions?

- What are examples of social persuasion and vicarious experiences that could be used by a personal trainer to influence physical activity self-efficacy?

- What are examples of coaching behaviors that would satisfy the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness?

- What are some efficacious strategies to reduce sedentary behavior?

- What factors correlate with both physical activity and sedentary behavior?

Glossary terms

- Physical activity: Any bodily movement produced by the skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure

- Sedentary behavior: Any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure ≤1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs), while in a sitting, reclining or lying posture

- Intentions: When people plan to act and perform a behavior.

- Attitudes: A valanced (favorable or unfavorable) evaluation about the behavior.

- Subjective norms: Perceived social influence from others to perform or not perform the behavior.

- Perceived behavioral control: The perception of performing the behavior as easy or difficult

- Self-efficacy: The degree of confidence to exert control over one’s behavior

- Past performance accomplishments: e.g., A runner achieving their personal best in a race

- Social persuasion: e.g., Encouragement from a friend to run

- Vicarious experiences: e.g., Observing others compete in races

- Interpretation of physiological and affective states: e.g., Awareness of positive feelings when running

- Decisional intention: Decisional direction to enact the behavior or not

- Intention strength: Intensity of commitment to enact behavior

- Self-determined motivation: The most optimal and highest quality motivation. This type of motivation includes intrinsic and extrinsic reasons tied to enjoyment, interest, and personal values

- Controlled motivation: The second type of motivation that includes reasons tied to external pressure and rewards

- Amotivation: The absence of intentions and sense of control to behave

- The need for autonomy: Individual authenticity in their behavioral decisions (i.e., sense of personal choice).

- The need for competence: Represents effective functioning (i.e., sense of ability to bring desired behavioral outcomes).

- The need for relatedness: Represents the social connectedness to others (i.e., sense that others accept, care for, and value an individual).

- The need for novelty: The need to experience something new or differs from experiences of everyday life.