Chapter 6: Personality and Physical Activity

Chapter Overview

Introduction

What is Personality?

Figure 6.1

Table 6.1

Personality Measurement

Personality and Physical Activity

Cross-sectional Associations

Correlational Associations: Personality and Physical Inactivity

Longitudinal Associations

Genetic Links between Personality and Physical Activity

Personality, Physical Activity, and Social Cognitions

Theory of Planned Behavior as a Mediator

Personality and Intentions

Self-Efficacy

Motives and Barriers

Personality, Physical Activity, and Affect

Personality, Physical Activity, and Mental Health

Personality and Physical Activity Preference

Considerations for Personality in the Promotion of Physical Activity

Table 6.2

Table 6.2 (continued)

Conclusion

Learning Exercises

Personality and Physical Activity

Chapter Overview

- Physical activity levels vary from person to person. Some of this variability comes from demographic differences (gender, age), or environmental differences (access to resources), but much of it goes unexplained. In this chapter, we explore the evidence that personality may influence how active people are.

- By the end of this chapter, readers should have a strong understanding of what personality is, how it relates to physical activity, and what are some of the causal mechanisms that might explain this relationship.

Introduction

- Physical activity is often the focus of public health initiatives as physical inactivity is a risk factor for chronic conditions. In addition to the protective effects of physical activity against physical illnesses, a wide body of evidence supports the benefits of physical activity on mental health and quality of life.

- Despite this, very few people engage in recommended levels of physical activity. In fact, less than 20% of US adults and adolescents engage in recommended levels of physical activity, a trend observed across developed nations.

- The purpose of this chapter is to provide students and practitioners with an overview of the evidence linking physical activity and personality, and to set the stage for continued work towards personality tailored approaches to exercise programming and physical activity promotion.

What is Personality?

- The American Psychological Association defines personality as “Individual differences in characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving.”

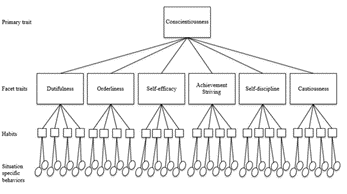

- Our current view of personality follows a common higher-order trait taxonomy, in which primary traits act as determinants of lower-order sub-traits which are used to describe individuals with greater specificity and detail, but which are also subject to greater influence by external factors.

- Thus, primary personality traits represent the peak of a conceptual hierarchy, with the most stable, biologically based traits at the top and individual level behaviors at the bottom, with narrow facet traits linking biological individual differences to situation specific individual level behavior.

Figure 6.1

What is Personality? (continued)

- Currently, the dominant contemporary taxonomy used by scholars worldwide is the Five Factor Model (FFM) of personality or similar variants of this model.

- This widely supported system postulates that the core personality of all people can be classified on five bipolar dimensions: (1) Extraversion/ Introversion; (2) Neuroticism/ Emotional Stability; (3) Conscientiousness/ Undirectedness; (4) Openness/ Closedness; and (5) Agreeableness/ Antagonism.

Table 6.1

Characteristic Tendencies of Individuals Scoring on the High or Low End of Each Bipolar Dimension of the Big Five personality Factors

|

Trait dimension |

High (+) / Low (-) Anchor Labels |

Characteristic Tendencies |

|

Extraversion |

(+) Extravert |

Sociable; assertive; energetic; excitement seeking; affectionate; talkative; friendly; warm; spontaneous; active; propensity towards positive affect. |

|

(-) Introvert |

Reclusive; reserved; aloof; quiet; inhibited; passive; cold; propensity toward negative affect under conditions of high stimulation. |

|

|

Neuroticism |

(+) Neurotic |

Emotionally reactive/unstable; anxious; self-conscious; vulnerable; high-strung; worrying; insecure. |

|

(-) Emotionally stable |

Calm; emotionally stable; secure; relaxed; self-satisfied; comfortable; unperturbed. |

|

|

Conscientiousness |

(+) Conscientious |

Orderly; dutiful; self-disciplined; achievement oriented; reliable; persevering; hardworking; punctual; neat; careful; well-organized. |

|

(-) Undirected |

Disorganized; negligent; undependable; poor time management/planning skills; lacking self-discipline. |

|

|

Openness |

(+) Open-minded |

Reflective; perceptive; creative; welcoming; unconventional; non-traditional; intellectual; original; imaginative; daring; complex; independent; broad interests. |

|

(-) Closed-minded |

Simple; pragmatic; conforming; traditional; unadventurous; “down to Earth”; conventional; uncreative; narrow interests. |

|

|

Agreeableness |

(+) Agreeable |

Lighthearted; easy going; cooperative; kind; optimistic; altruistic; trustworthy; generous; soft-hearted; forgiving; sympathetic; acquiescent; selfless; good-natured; lenient; trusting. |

|

(-) Antagonistic |

Ruthless; vengeful; callous; selfish; irritable; critical; suspicious; argumentative; cynical; competitive. |

|

Personality Measurement

- Personality assessment can be approached via self-or proxy-report survey, behavioral observation, or the measurement of psychophysiological correlates

- Most frequently, personality is assessed using a validated self-report measure. Survey assessments ask people to rate how well an adjective or sentence describes themselves or someone they know.

- Unlike survey assessments, behavioral observations and psychophysiological measures are uninfluenced by participant response bias. To date, observational assessments of personality are rarely used in the exercise and physical activity literature.

- Psychophysiological correlates of personality can be used as a proxy measure for biologically based traits. Like behavioral observation, the assessment of psychophysiological correlates of personality in the exercise and physical activity literature has been underutilized.

Personality and Physical Activity

- Currently the cumulative evidence supports a modest relationship between personality and physical activity, as well as physical inactivity, and sedentary behavior.

- These relationships appear robust across the lifespan and some evidence suggests that associations are bidirectional.

- Most of the evidence on personality and physical activity is derived from cross-sectional and longitudinal observations.

Cross-sectional Associations

- The relationship between personality and physical activity has received intermittent attention over the past 50 years.

- Based on the cumulated evidence, it can be concluded that self-reported physical activity has a reliable, yet small positive association with Extraversion and Conscientiousness. Also, Neuroticism appears to have a negative relationship with self-reported physical activity.

- Though relationships between personality and self-reported physical activity are highly consistent, there is relative paucity of evidence reporting on these relationships using objective measures (e.g., pedometers, accelerometers) of physical activity.

Correlational Associations: Personality and Physical Inactivity

- In examining relationships between traits and a dichotomous inactivity variable (i.e. inactive or not inactive), data suggest that for every standard deviation (SD) unit increase in Extraversion, Conscientiousness, or Openness, there is about a 10-15% decrease in risk for inactivity.

- In contrast, for every SD increase in Neuroticism, there is a 10% increase in risk for inactivity. Further, Neuroticism appears consistently positively related, and Conscientiousness consistently negatively related, with total time spent sedentary.

- Evidence for associations between sedentary behaviors and Extraversion and Openness is mixed, and Agreeableness appears unrelated to sedentary behavior.

- Overall, the associated evidence on personality and sedentary behavior is still in its infancy.

Longitudinal Associations

- Most of the evidence linking physical activity and personality describes bivariate associations observed in cross-sectional or very brief longitudinal investigations (e.g., 8 weeks).

- A few studies have examined the interconnected relationship between personality and physical activity across extended periods of time. Repeated measures over time allow for an assessment of the direction of effects between variables, and the stability of these effects over time.

- Some evidence supports a beneficial effect of physical activity on personality change over time. A recent report showed that lower physical activity was associated with declines in Conscientiousness, Openness, Extraversion, and Agreeableness over the course of 20 years, although the effect sizes were very small.

- Though the existing longitudinal research is encouraging, the hypothesis of bidirectionality has mixed support, highlighting the need for further investigation.

Genetic Links between Personality and Physical Activity

- The cumulative associative evidence begs the question of genetic overlap between personality and physical activity level.

- Heritability estimates for the Big Five traits range from 41% to 61%, and physical activity is heritable in the range of 48% to 71%.

- In a 2018 study (de Moor & de Geus), the association between Neuroticism and physical activity was observed to be the result of a shared genetic source, whereas the association between Extraversion and physical activity was partly due to shared genes, but also partly due to a causal impact of Extraversion on physical activity behavior.

- The genetic association between Extraversion and physical activity was again corroborated in a sample (n =373) of adolescent and young adult twins (Schutte et al., 2019).

- Additional research is needed to test the reproducibility and generalizability of these compelling observations in more diverse samples, but early results suggest a common genetic etiology between physical activity behavior and primary traits Neuroticism and Extraversion.

Personality, Physical Activity, and Social Cognitions

- Though describing direct relationships between personality and physical activity is an important first step, it is important to specify how personality may affect physical activity behavior.

- Specifically, the influence of personality is hypothesized to be indirect, working through social cognitions (e.g., perceptions, attitudes, norms, self-efficacy), habits, or social and environmental access to behavioral resources (Ajzen, 1991; Bogg et al., 2008; McCrae & Costa,1995; Rhodes, 2006).

- Several studies have examined social cognitive theories as mediators of the personality–physical activity relationship (Rhodes & Pfaeffli, 2012; Rhodes & Wilson, 2020; Wilson, 2019).

Theory of Planned Behavior as a Mediator

- Rhodes and Pfaeffli (2012) conducted a systematic review and reported that personality was related to theory of planned behavior constructs, and that personality and social cognitive constructs were related to physical activity. However, the test of full mediation was only supported in two samples.

- A more complex analysis subsequently revealed that a sub-trait of Extraversion, the activity trait, accounted for the observed relationship between Extraversion and social cognitive constructs.

- Hagan et al. (2009) reported that the activity trait mediated the relationship between Extraversion and theory of planned behavior constructs, and that attitude and perceived behavioral control mediated the relationship between the activity trait and physical activity behavior (Hagan et al., 2009).

- All other studies only supported partial mediation, as personality had significant direct effects on physical activity. The finding is interesting because it shows that personality may have another route on behavior beyond reflective social cognitions (e.g., intention, attitude, perceived control).

Personality and Intentions

- Given that intention is considered the proximal determinant of behavior in most social cognition models (Conner & Norman, 2015), investigations have examined the possibility of moderation and mediation in the context of multivariate models including personality, social cognitions, and behavioral intention.

- Cumulative associative evidence points to moderation of the intention-behavior gap by personality traits, specifically Conscientiousness. Two systematic reviews have concluded that Conscientiousness interacts with intention to impact physical activity level (Rhodes & Dickau, 2013; Wilson & Dishman, 2015).

- A recent meta-analysis examined moderation according to whether or not participants were asked how active they intended to be prior to an impending physical activity measurement and found that associations between Conscientiousness and physical activity were twice as large in studies that asked about intention compared to those that did not (Wilson & Dishman, 2015).

- Moreover, a review of moderators of the physical activity intention-behavior gap concluded that Conscientiousness significantly moderates the intention-behavior relationship, such that higher levels of Conscientiousness are associated with stronger positive intention-behavior relationships (Rhodes & Dickau, 2013).

Self-Efficacy

- Personality and physical activity have also been examined in the context of their common relationships with self-efficacy.

- In a population cohort (n= 3,471), general self-efficacy was observed to partially mediate the relationships between all of the Big Five personality factors and self-reported moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and leisure time inactivity (Ebstrup et al., 2013).

- Observed relationships between personality and physical activity were consistent with previous meta-analyses (Rhodes & Smith, 2006; Wilson & Dishman, 2015), but when general self-efficacy was added to the prediction model a significant relationship between Agreeableness and physical activity, not previously supported, was revealed. Mediation by self-efficacy was also observed in a sample of older adults (n = 876; >60 years).

- There is also some evidence demonstrating that self-efficacy to overcome barriers interacts with Neuroticism to predict physical activity (Smith, Williams, O’Donnell, & McKechnie, 2016).

- This interaction could indicate that strategies for increasing low barrier self-efficacy may be particularly important for individuals scoring high on Neuroticism. More work is needed to confirm this interpretation.

Motives and Barriers

- Another possible explanation for the relationships between personality and physical activity is through its effect upon exercise barriers and motives.

- Though sparse, existing evidence does indicate that Neuroticism is positively related, and Conscientiousness and Extraversion are negatively related to exercise barriers like fear of embarrassment, lack of motivation, and/or lack of energy.

- Higher levels of Agreeableness and Conscientiousness were related to greater physical, rather than psychological, motivation for exercise, whereas higher levels of Emotional Stability, Extraversion, and Openness were related to greater psychological motivation for exercise

- Work by Lochbaum and colleagues (2013) suggests that the relationship between Extraversion and exercise participation is fully mediated by approach oriented goals to achieve skill mastery, whereas the relationship between Neuroticism and exercise participation was only partially mediated by approach/avoidance goals related to performance compared to others (Lochbaum et al., 2013).

Personality, Physical Activity, and Affect

- Personality has close direct relationships with the propensity to experience positive and negative affect, and to enhance affective responses to a wide range of stimuli. Affective responses to physical activity and expectations of enjoyment are both reliable correlates of future physical activity behavior.

- The fundamental basis for personality development, as discussed previously, lies in temperament. From this perspective, it is intuitive that personality differences might impact how one responds affectively to the uniquely arousing stimulus of exercise.

Personality, Physical Activity, and Mental Health

- Across the recent investigations in this area, scholars have tested whether personality moderates the mental health impact of physical activity, and whether physical activity mediates the relationships between personality and mental health.

- Observations from research in this area indicate that the relationships between general symptoms of mental distress and physical activity are dependent on personality characteristics, and individuals with personality profiles that put them at higher risk for mental distress may benefit from greater levels of fitness and physical activity participation.

- Advancing our understanding of the role of personality in the effectiveness of physical activity and exercise for easing mental distress among clinical populations is an important corollary to this effort, and an area ripe for further investigation.

Personality and Physical Activity Preference

- Relationships between personality and physical activity are likely confounded by the way physical activity is conceptualized within studies.

- In their systematic review of personality and physical activity, Rhodes and Smith (2006) outlined five studies that explored personality with a particular mode or modes of physical activity.

- Differences in preferences for exercise intensity are theoretically expected for Extraversion specifically, as extraverts are expected to experience positive hedonic tone at greater stimulus intensities than those who are more introverted (Eysenck et al., 1982).

- Understanding physical activity preferences in the context of personality may help exercise practitioners identify types of activities that new clients may be likely to enjoy, assisting in the effort to promote exercise adherence (e.g., Newsome et al., 2021).

Considerations for Personality in the Promotion of Physical Activity

- Evidence suggests that personality may be a useful tool for professionals who are attempting to reduce the risk of disease by increasing physical activity level.

- Evidence linking personality to preference for, or responsiveness to, specific behavior change techniques could inform the continued efforts towards intervention adaptions according to personality.

- Though emerging evidence is encouraging, direct tests of strategies targeting individual differences in personality have yet to be reported for interventions aiming to increase physical activity

Table 6.2

|

Trait expression |

Promotion and Programming Considerations |

|

(+) Extravert |

Preferences include moderate-to-vigorous intensity, and activity with others. Motivated to exercise for enjoyment. May tend to go “too hard, too fast”; emphasize safe progression and recovery. |

|

(-) Introvert |

Likely to have an initial preference for lower intensities. Tend to avoid exposure to excessive sensory stimuli; recommend restorative and mindful activities. Likely to enjoy exercise alone or with a close friend. Outdoor or home exercise settings may enhance activity enjoyment. |

|

(+) Neurotic |

More likely to remain inactive due to embarrassment. Primary exercise motives related to appearance. Derive less enjoyment from exercise than others. Likely to benefit from strategies to enhance self-efficacy to overcome barriers related to physical activity/exercise, and programming to focus on short term, realistic goals. Focusing on the mental health benefit of exercise as a motivator may enhance adherence. |

|

(-) Emotionally Stable |

Pay attention to self-reported goals and logical program progression. Provide a means for feedback and self-monitoring. |

|

(+) Conscientious |

Very good at setting short- and long-term goals and creating action plans for success. Recommend long-term adherence as a focused goal. Self-monitoring techniques are typically well implemented, and feedback appreciated. May prefer higher intensity activities. |

|

(-) Undirected |

High risk for drop out, especially during times of high stress. Poor planning and goal setting skills. Be mindful of upcoming life events that may disrupt normal participation. Not motivated by tracking or feedback techniques. Social accountability with an important other is advisable. Try to identify activities that are challenging yet enjoyable to promote adherence. |

|

(+) Open-minded |

Variety may help facilitate adherence. May prefer outdoor and adventure activities. Make programming suggestions but promote autonomy in program development. |

|

(-) Closed-minded |

May challenge new ideas or unusual approaches (not likely to adopt the latest trend). Stick to traditional exercise programming. Highlight the evidence supporting programming development. |

|

(+) Agreeable |

Generally cooperative and easy going. Likely to take instruction well. May benefit from motivational interviewing to understand exercise preferences. |

|

(-) Antagonistic |

Likely to enjoy competition with oneself or others, and to be achievement oriented. Include progress checks and feedback while working towards short and long-term goals. |

Conclusion

- Currently the cumulative evidence supports a modest relationship between personality and physical activity. In particular, self-reported physical activity has a reliable, yet small positive association with Extraversion and Conscientiousness and a small negative relationship with Neuroticism.

- There is a body of evidence that personality traits may play a role in social cognitive constructs such as attitudes, enjoyment, self-efficacy, barriers/motives, and intention.

- The relationships between general symptoms of mental distress and physical activity are dependent on personality characteristics.

- Much evidence exists on the relationships between personality and physical activity, though more work is required to understand genetic, cognitive, and affective mechanisms, developmental associations across extended periods of time, and the development and implementation of personality adapted physical activity promotion strategies.

Learning Exercises

- What is personality? Define personality in one sentence.

- Describe the relationships between primary personality traits and physical activity in terms of direction and strength.

- What are some social cognitive variables that have been studied in the context of personality and physical activity? How do these variables relate to personality and physical activity?

- Based on what you know about the primary personality dimensions, what are some programming recommendations you would make for someone who is extremely extraverted? Introverted?

- Have a friend complete one of the five factor personality measures available on the ipip website. Create exercise recommendations for them based on their survey responses.

Glossary Terms

- Personality: Individual differences in characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving (American Psychological Association, 2020).

- Five Factor Model (FFM) of personality: A widely supported system that postulates that the core personality of all people can be classified on five bipolar dimensions: (1) Extraversion/ Introversion; (2) Neuroticism/ Emotional Stability; (3) Conscientiousness/ Undirectedness; (4) Openness/ Closedness; (5) Agreeableness/ Antagonism. (McCrae & Costa, 2008; Revelle et al., 2011)

- Distractor: Survey items that do not ask about personality characteristics, attempting to conceal the purpose of the survey from the participant.

- International Personality Item Pool (IPIP): A free resource in the public domain including more than 3,000 items from over 250 personality scales which are available to be copied, edited, translated or otherwise used for any purpose without seeking permission or paying a fee for use (Goldberg, 1999; Goldberg et al., 2006).

- Extraversion: Reserved, thoughtful vs. sociable, fun-loving

- Agreeableness: Suspicious, uncooperative vs. trusting, helpful

- Openness: Prefers routine, practical vs. imaginative, spontaneous

- Conscientiousness: Impulsive, disorganized vs. disciplined, careful

- Neuroticism: Calm, confident vs. anxious, pessimistic