Chapter 7: Body Image and Physical Activity

Chapter Overview

What is Body Image?

Appearance and Function Facets

Multidimensional Construct

Figure 7.1

Perceptual Dimension

Cognitive Dimension

Affective Dimension

Behavioral Dimension

Positive and Negative Facets

Body Image Investment

Body Image Internalization

Similarities and Differences between Body Image and Physical Self

Body Image Pathologies

How Does Body Image Develop?

Measuring Body Image

Body Image and Physical Activity

Bidirectional Relationship

Mechanisms Linking Physical Activity and Body Image

Actual and Perceived Body Change

Self-Efficacy and Control

Motivation

The Exercise and Self-Esteem Model

Key Considerations for Body Image Research

Need for Varying Study Designs

Longitudinal Studies

Intervention Studies

Mixed-Method Studies

Theory Development and Testing

Individual Differences

Age

Gender

Race, Ethnicity, and Culture

Sexual Orientation

Intersectionality

Conclusion

Learning Exercises

Body Image and Physical Activity

Chapter Overview

- Body image is an important construct worthy of examination in physical activity contexts, as it is a notable correlate, antecedent, and outcome of physical activity behavior (Sabiston et al., 2019).

- Within this chapter, the definition and components of body image will be described including the appearance and function facets, four dimensions, positive and negative valence, and body image investment and internalization.

- Throughout this chapter, the bidirectional relationship between body image and physical activity is outlined and potential mechanisms that help to explain this relationship are presented.

What is Body Image?

- Within the fields sport and exercise psychology, body image is a central factor given its relevancy in the initiation, maintenance, and withdrawal of physical activity (Sabiston et al., 2019).

- The relationship between body image and physical activity is complex, and understanding this interrelationship is key to improving the physical activity experience and increasing and sustaining sport and exercise behaviors across populations.

- Body image is most commonly defined as a multidimensional construct that includes how one sees, thinks, feels, and behaves related to their body’s appearance and function (Cash & Smolak, 2011)

Appearance and Function Facets

- Body image includes the appearance (i.e., what the body looks like) and function (i.e., what the body can do) of the body.

- Body image research has predominantly focused on the appearance facet. How an individual describes and thinks about their appearance is bi-directionally associated with sport and exercise behaviors and experiences (Sabiston et al., 2019). The way an individual perceives and thinks about their appearance can enhance or limit their participation in physical activity or alter their physical activity experiences.

- Conversely, focusing on the body’s function results in greater positive thoughts and feelings towards the body and more adaptive body image behaviors (Abbott & Barber, 2011; Alleva, Martijn,et al., 2015).The physical activity environment often encourages identity building that involves physical competence and mastery, supporting a focus on body functionality.

Multidimensional Construct

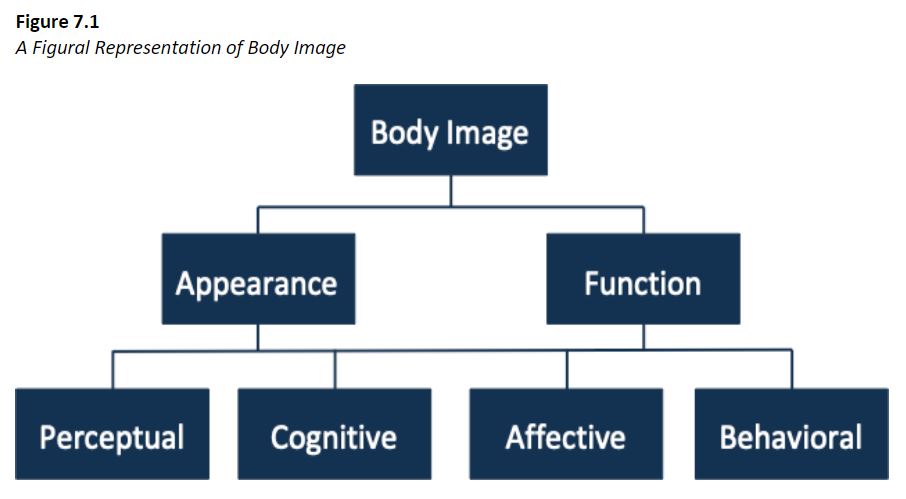

- In addition to the appearance and function facets, the dimensions of body image include the perceptual, cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions (Cash & Smolak, 2011). A general schematic of body image is presented in Figure 7.1. Body-related perceptions, cognitions, and feelings influence behaviors related to the body.

Figure 7.1

A Figural Representation of Body Image

Perceptual Dimension

- The perceptual dimension of body image refers to the mental representations that an individual holds related to their own body’s appearance and function.

- The mental representation is usually defined as the accuracy level between perceived and actual characteristics, as it relates to the body as a whole or specific body parts (e.g., legs, arms, torso; Cash & Smolak, 2011).

- Importantly, an individual’s mental representation is not always accurate and may widely vary from their actual self. Furthermore, these body perceptions do not indicate the thoughts, satisfaction, dissatisfaction, or feelings that are attributed to this perceived self

Cognitive Dimension

- The cognitive dimension of body image refers to individuals’ thoughts, beliefs, and evaluations of their body’s appearance and function. Body image is most commonly assessed as the cognitive dimension.

- For example, cognitive body image includes body dissatisfaction (or satisfaction) assessments, where an individual indicates their level of satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) with their body’s appearance and/or function.

- In terms of appearance, (dis)satisfaction measures ask participants to indicate their (dis)satisfaction with particular body parts (e.g., torso, face, legs) or attributes (e.g., thinness, weight, muscularity).

Affective Dimension

- The affective dimension of body image describes the feelings and emotions that individuals experience in relation to their body’s appearance and function.

- These feelings and emotions are commonly assessed as social-physique anxiety and body-related self-conscious emotions

- Social-physique anxiety is defined as the anxiety an individual feels as a consequence of perceived or actual judgments from others (Hart et al., 1989).

- Body-related shame and guilt are both negatively-valenced self-conscious emotions, yet shame has a global focus on the self (e.g., “I am a person who is unattractive”), while guilt focuses on a specific behavior (e.g., “I do not do enough to improve the way I look”).

Behavioral Dimension

- The behavioral dimension of body image depicts an individual’s decisions and actions that are informed by their perceptions, cognitions, and emotions related to their appearance and function.

- These actions often fall under two negatively-valenced components (i.e., appearance fixing and avoidance) and one positively-valenced component (i.e., positive rational acceptance).

- Negative body image can motivate engagement or avoidance of behaviors, such as physical activity. Positive rational acceptance comprises engagement in adaptive cognitive and behavioral actions such as positive self-care and rational self-talk.

Positive and Negative Facets

- The four dimensions of body image can be positive and/or negative. Positive body image refers to an overall love and respect towards the body’s appearance and function and includes an appreciation and acceptance of the body.

- In relation to the dimensions, positive body image may be expressed as accurate perceptions of the body, positive thoughts, beliefs (e.g., satisfaction), and feelings (e.g., pride) toward the body, and health-promoting and adaptive behaviors (e.g., positive self-care).

- Conversely, negative body image involves the pathological aspects of body image and can be expressed as inaccurate perceptions, negative thoughts, beliefs (e.g., dissatisfaction), and feelings (e.g., shame, guilt), and risky or maladaptive behaviors (e.g., excessive exercise).

- It is crucial to note that positive body image is distinct from negative body image. These constructs do not exist on the same continuum; low levels of negative body image do not suggest high levels of positive body image.

Body Image Investment

- In addition to the four body image dimensions, body image also integrates an investment component that involves the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional importance an individual places on their body’s appearance (Cash, 2012).

- The amount that one is invested in their body defines how an individual sees, thinks, feels, and behaves toward their body. Body image investment is often assessed by measuring the beliefs and assumptions about the importance, meaning, and influence of body appearance in an individual’s life

- Those who tend to be more invested in their body’s appearance may experience greater worry and be more preoccupied with what their body looks like. More invested individuals also tend to use greater maladaptive body image coping strategies.

Body Image Internalization

- Body ideals are highly encouraged in societies and are transmitted through various sources. The commonly maintained westernized body ideals include thinness for women and muscularity for men.

- Although these body ideals are widely unrealistic for the majority of the population, many individuals adopt these appearance ideals and compare their appearance, shape, and size to the widespread ideals. This leads the majority of those who internalize idealizations of the body to experience negative body image

- Those who reject the mainstream body ideals are less likely to experience negative body image and potentially harmful exercise behaviors.

Similarities and Differences between Body Image and Physical Self

- In sport and exercise psychology, terms of body image and physical self-concept have been used to generally refer to self-esteem focused on the body or physical features of the body. The terms of body image and physical self-concept have been used interchangeably by some researchers, and with intentional and purposeful distinctness by other researchers.

- Body image is a broader construct providing more depth and understanding to acceptance, importance, and evaluation of body appearance, weight, and body shape; whereas the physical self is a focused descriptive account on appearance and body fat as the only body-specific descriptions coupled with specific perceptions of body-related function/competence.

- Both body image and physical self-concept generally lack integration into physical activity, exercise, or sport theories. Nonetheless, both constructs have been identified as having bidirectional relationships with physical activity, exercise, and/or sport behaviors.

Body Image Pathologies

- Individuals who have excessive frequent and intense negative thoughts about their appearance may experience body image concerns that are clinically meaningful. Body image pathology is recognized as disorders by psychiatric standards (e.g., American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

- Body dysmorphia is described as over exaggerated and inaccurate perceptions of flaws related to body parts and characteristics and a preoccupation with flaws that severely limits an individual’s daily functioning and quality of life (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Symptoms of body dysmorphia may include a heightened focus, comments, and discussions about one’s perceived flaws, body monitoring and checking behaviors, and also individuals in sport and exercise settings may demonstrate withdrawal from others or constant need for reassurance from coaches, teammates, personal trainers, and others in leadership positions.

- Some people who experience body dysmorphic disorder are also diagnosed with an eating disorder. Eating disorders are recognized mental disorders that are defined as abnormal eating habits resulting in insufficient or excessive consumption of food (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, and binge eating disorder are three commonly recognized eating disorders.

How Does Body Image Develop?

- There are a number of perspectives used to generally describe the development of body image, and specific possible outcomes related to eating disorders. The models and theories that will be presented in this chapter include the tripartite influence model, social comparison theory, and self-discrepancy theory.

- The tripartite influence model (Thompson et al., 1999) suggests that there are formative social factors that influence the development and maintenance of negative body image and disordered eating. As the name indicates, parents, peers, and media are the three primary social influences proposed to form the basis for later development of body image concerns and eating dysfunction

- Festinger’s social comparison theory (1954) states that individuals have an inherent need to evaluate their appearance and abilities against others. According to social comparison theory, individuals either compare themselves to those who are worse off (called downward social comparison) or better off (called upward social comparison) than they are on attributes of value (e.g., appearance, body shape, physical skill).

- According to the self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987), individuals who value and invest in body attributes such as attractiveness and/or competence in physical activity are more likely to desire these attributes. When these attributes are not feasibly or naturally attainable, a discrepancy is created between an individual’s actual body and “desired” or ideal body.

Measuring Body Image

- While earlier measures of body image focused predominantly on the pathology of body image and more negative perceptual, cognitive, affective, and behavioral implications, there have also been a number of scales recently assessing positive perceptions, cognitions, emotions, and behaviors.

- Perceptual measures compare an individual’s body perception and their actual body shape and size. When there is a weighting or value component to these perceptions, it becomes a cognitive measure.

- The cognitive dimension of body image is often assessed using measures of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with an individual’s body shape, size, weight, and functionality/competence.

- The affective dimension of body image is measured by capturing individuals’ body-related feelings and emotions that often include anxiety, shame, embarrassment, guilt, pride, and envy. Most affective measures are self-report, and often include frequency and/or intensity of emotional experiences.

- The behavioral body image dimension is often measured based on avoidance or engagement in behaviors such as physical activity, diet/eating, or substance use. Individuals are asked to report on the frequency of participation in these types of behaviors, as well as general avoidance of situations or events because of their body image.

Body Image and Physical Activity

- Positive and negative body image is associated with numerous behavioral outcomes, including physical activity.

- Physical activity is a context where individuals often engage in social comparisons, are evaluated based on physical and functional features, and experience judgment from others based on their appearance and function.

- These aspects may contribute to experiences of negative body image. Yet, physical activity can also be an outlet where individuals experience mastery, enjoyment, and positive affect experiences, which can foster positive body image.

- In this section, we outline the relationship between body image and physical activity in greater detail and identify mechanisms that may influence this relationship.

Bidirectional Relationship

- Body image and physical activity have a bidirectional relationship, meaning that one’s positive or negative body image can influence their participation in physical activity, and one’s participation in physical activity can influence their body image (negatively or positively; Sabiston et al., 2019).

- Among the limited literature available, negative body image is associated with lower activity and is described qualitatively as a barrier to physical activity, while positive body image is associated with greater physical activity behavior (Sabiston et al., 2019)

- To establish a deeper understanding of the bidirectional relationship between body image and physical activity, it is critical that the mechanisms that explain this relationship are explored.

Mechanisms Linking Physical Activity and Body Image

- The majority of quantitative studies examining body image in sport and exercise psychology have been cross-sectional (Sabiston et al., 2019).

- Much of this research, however, has been atheoretical, and as such, a deeper understanding of the mechanisms explaining these relationships is needed.

- While there are numerous theories linking components of physical activity with body image, there are three likely mechanisms that can advance our understanding of physical activity and body image.

- Specifically, individuals’ perceptions of their body, efficacy beliefs, and motivation are discussed as potential mechanisms that can explain associations between exercise and body image.

Actual and Perceived Body Change

- Due to the strong emphasis placed on a lean physique in western societies, researchers have focused on whether improvements in physiological changes in the body explain the relationship between higher levels of physical activity and improved body image. However, there is only weak evidence suggesting this is the case, with the majority of evidence demonstrating inconclusive results (Martin-Ginis, Bassett-Gunter, et al., 2012).

- Although there is a positive relationship between body composition and body image (Rinaldo et al., 2016), it appears physical activity-induced changes in body composition do not improve body image. Instead of objective body change improvements, it may be that ones’ perceptions of body improvements as a result of physical activity are related to body image.

- Collectively, interventions studying this change (Martin Ginis, McEwan, et al., 2012) indicate that the perception of fitness improvements after increased physical activity, as opposed to actual improvements, is the primary factor responsible for inducing changes in body image.

Self-Efficacy and Control

- In addition to the perceptions of fitness improvement, individuals’ belief in their capabilities pertinent to physical activity is likely an important mechanism explaining the relationship between physical activity and body image (McAuley et al, 2000; McAuley et al., 2002).

- Researchers suggest that self-efficacy might mediate this relationship due to feelings of empowerment and control, whereby individuals feel like they have control over their environment (Martin-Ginis, Bassett-Gunter, et al., 2012).

- While the mediating effect of control has yet to be examined, attributing successful exercise outcomes to controllable reasons (e.g., good time management) strengthens the effect of physical activity on body image (Murray et al., 2021).

- However, further research is needed to understand whether body image improves because individuals feel higher levels of self-efficacy and perceptions of control after increased physical activity

Motivation

- Self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2002) might be applicable in understanding motivation as a mechanism to explain the relationship between body image and physical activity.

- According to self-determination theory, motivation lays on a continuum from external motivation to internal motivation, with individuals who are externally motivated being less likely to engage in sustained exercise behavior (Ingledew & Markland, 2008).

- Therefore, engaging in physical activity to improve appearance is likely associated with more external levels of motivation, meaning individuals are less likely to continue to exercise.

- Levels of motivation have not been explicitly tested as a mechanism of the relationship between exercise and body image and therefore is a potential avenue for further research.

The Exercise and Self-Esteem Model

- The exercise and self-esteem model (EXSEM) explains associations between physical activity and general self-esteem, to which body image is an important contributor.

- The EXSEM suggests that participation in physical activity increases self-efficacy then perceptions of physical competence, which in turn boosts general self-esteem.

- Researchers testing the EXSEM have observed body image to be an important component of general self-esteem (Fernández Bustos et al., 2019; Martin-Ginis et al., 2014), especially during adolescence-a time when perceptions of the physical self are of heightened importance (Harter et al., 2012).

- To date, the EXSEM has shown to be a valuable model guiding research on the mechanisms that explain relationships between physical activity and body image.

Key Considerations for Body Image Research

- In this section, a description of the limitations of the existing work on body image and physical activity is presented.

- In addition, different research approaches that will provide a richer understanding of these relationships are described. Specifically, future considerations within the topics of longitudinal, interventional, and mixed-methods study designs, theory development and testing, and individual differences are outlined.

- A focus on the key issues to be addressed in future research and practice is provided.

Need for Varying Study Designs

Longitudinal Studies

- The likely bidirectional nature of the relationship between body image and physical activity necessitates longitudinal research. Longitudinal studies examining physical activity, sport, exercise, and body image might disentangle the nature of these relationships, elucidating predictive associations.

- Recent longitudinal research (Pila et al., 2020; Sabiston, Pila,et al., 2020) highlights that in the context of sport, adolescent body image is an ever-changing process, which requires measurement at multiple occasions.

- While researchers have yet to explore how sport and exercise relate to body image across the life span, body image and self-perceptions are known to change over time (Orth et al., 2010), understanding how physical activity, sport, and exercise contributes to these changes is a worthwhile endeavor.

Intervention Studies

- Intervention studies are needed to bridge the gap between research and applied practice.

- Regardless of the positive relationship between physical activity and body image, interventions aiming to improve body image through increasing physical activity opportunities are not efficacious (Alleva, Sheeran,et al., 2015).

- Indeed, researchers have observed that exercising to avoid feelings of guilt and shame are not conducive to sustained participation (Assor et al., 2009), with appearance based motives weakening the association between body image and exercise frequency (Homan & Tylka, 2014).

- Alternatively, researchers should test the efficacy of focusing on body functionality instead of appearance to facilitate exercise frequency through body image (Alleva, Sheeran,et al., 2015).

- Taking steps to reduce the emphasis on the body’s appearance in sport and exercise settings may be an effective strategy to reduce negative body image outcomes.

Mixed-Method Studies

- There is a dearth of mixed-methods studies examining associations between exercise and body image. Taking both quantitative and qualitative approaches to the study of exercise and body image is a necessary step to understand why sport and exercise are positively and negatively associated with body image (Sabiston et al., 2019).

- For example, many quantitative studies examining physical activity and body image indicate a positive association (Hausenblas &Downs, 2001), however, qualitative samples describe situations in which sport and exercise settings contribute to negative body image (Vani et al., 2020).

- Mixed-methods studies can be used to understand trends in physical activity and body image while identifying the aspects of sport and exercise settings that contribute to negative and positive body image.

Theory Development and Testing

- Although several theories have been described within this chapter, a theory of body image and physical activity has not yet been developed.

- The lack of a theory hinders the advancement of understanding mediators and moderators of the body image and exercise relationship.

- A basic model of exercise and body image was developed by Martin Ginis, Bassett-Gunter, and Conlin (2012) that outlines potential mediators (e.g., changes in self-efficacy) and moderators (e.g., intensity level, sex) of the relationship from exercise to body image. However, this was designed to guide researchers to choose measures to include in exercise interventions and it doesn’t include the potential effects of mediators and moderators in the relationship from body image to exercise.

- Developing a theory that addresses the bidirectional relationship between body image and exercise is needed.

Individual Differences

- There are many personal characteristics that relate to body image in sport and exercise settings.

- Below, four characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation) are discussed, however, it is important to note that there are many other individual differences beyond those discussed in this chapter which likely impact these relationships.

Age

- Research on body image in sport and exercise typically focus on adolescents and young adults (Sabiston et al., 2019) and as such, many of the relationships discussed in this chapter pertain to this younger demographic.

- As individuals progress across the lifespan, they typically experience more positive and less negative body image. The importance of body shape, weight, and appearance typically decreases as individuals progress into later adulthood (Tiggemann, 2004).

- While body image plays a strong role in adolescents and young adults’ physical activity experiences, the decreasing importance of body image in adulthood may result in better physical activity experiences for adults.

- In short, those who disengage from sport and exercise as adolescents may have better experiences as adults. Further research is needed to test these claims and develop an understanding of how body image relates to physical activity across the lifespan.

Gender

- Body image is relevant to all genders; however, societal influences encourage different body image standards for boys/men and girls/women with a higher emphasis for girls and women to be slender and toned, but not muscular, while men are pressured to be muscular.

- In the sport and physical activity context, the ideal body of being muscular aligns with the ideal man’s body but does not align with the ideal women’s body (Lunde & Gattario, 2017). This can lead to the perception that sport and exercise align more with the masculine identity than the feminine identity, thus discouraging participation in girls and women.

- Importantly, discussion on body image in sport and exercise settings among individuals who identify as non-binary, transgender, or two-spirit is lacking. Further research on these populations is needed to understand which sport and exercise settings facilitate or inhibit participation among non-binary individuals, and how this impacts their body image

Race, Ethnicity, and Culture

- The extent to which race and ethnicity impact body image in sport and exercise settings is relatively unknown.

- When examining physical activity levels, there is inconsistent evidence on the differences in physical activity levels between Black and White adolescents (Butt et al., 2011; Trost et al., 2002).

- Most of the research outlined in this chapter pertains to individuals who identify as White; however, early evidence indicates there are marked differences between body image within different racial groups.

- Research purposefully examining the relationship between exercise and body image in racially and ethnically diverse samples is needed to further our understanding of body image and physical activity.

Sexual Orientation

- Research investigating exercise and body image among those who identify with sexual orientations that differ from heterosexual is also limited.

- There is evidence however that gay men and heterosexual women may be more motivated to engage in exercise for appearance related purposes when compared to heterosexual men (Grogan et al., 2006).

- This research indicates there are likely meaningful differences in body image experiences between gay, lesbian, and heterosexual participants in sport and exercise settings.

- Research understanding these differences and how individuals of varying sexual orientations (e.g., bisexual, gay, lesbian, pansexual, queer) experience body image in sport and exercise settings may provide valuable knowledge that can encourage more inclusive sport and exercise environments.

Intersectionality

- There is a lack of research understanding intersectionality in sport, particularly in terms of understanding the impact of individual identities (e.g., Black, lesbian, woman, able-bodied) in the sport and exercise context and how these relate to perceptions of body image.

- For example, in the sport context, the gay body and the athletic body may be perceived as markedly different (Morrison & McCutcheon, 2012).

- Further research is needed to understand how intersectionality impacts physical activity and body image experiences.

Conclusion

- Body image is multidimensional, involves the appearance and function of the body, includes investment and internalization of ideals, and can be negative and/or positive.

- Body image has been studied using a number of theories, models, and measures, and is a key factor in the development of body dysmorphia and eating disorders. Further, body image shares a complex bidirectional relationship with physical activity.

- Despite this established association, the mechanisms that explain this relationship are not fully understood.

- Within the limited research, there is preliminary evidence to suggest that perceived body changes, self-efficacy and control, and motivation might help to explain the link between body image and physical activity.

Learning Exercises

- Define body image and the four dimensions of body image described in this chapter. Provide one example of how you would measure each dimension.

- Consider whether positive and negative body image are on the same or separate continuums. Name one positive and one negative body image construct that fall within the affective and cognitive dimensions.

- Compare and contrast body image and the physical self.

- What are some of the factors that can influence the development of body image?

- Describe the bidirectional relationship between body image and physical activity. Outline two mechanisms that link body image and physical activity.

- Choose two individual differences and explain how they relate to body image in sport and exercise settings.

- You are tasked with designing a fitness facility and creating guidelines for this new facility. Your goal is to avoid body-related evaluations. What important factors would you consider?

- You are creating a social media account to promote body positivity within a movement context (e.g., physical activity, sport, exercise). Based on what you have learned in this chapter, what movement setting would you choose, what population would you target, and what principles you would uphold?

Glossary Terms

- Intersectionality: The interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender as they apply to a given individual or group, regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage.

- The exercise and self-esteem model (EXSEM): A model which explains associations between physical activity and general self-esteem, to which body image is an important contributor (Soenstrom& Morgan, 1989; Soenstromet al.,1994).

- Self-determination theory: Belief that motivation lays on a continuum from external motivation to internal motivation, with individuals who are externally motivated being less likely to engage in sustained exercise behavior (Ingledew & Markland, 2008).

- External motivation: Engaging in a behavior due to external pressure

- Internal motivation: Engaging in a behavior because it is enjoyable

- Self-efficacy: Individuals’ belief in their capabilities pertinent to physical activity

- Behavioral body image dimension: Measured based on avoidance or engagement in behaviors such as physical activity, diet/eating, or substance use.

- Affective dimension of body image: Measured by capturing individuals’ body-related feelings and emotions that often include anxiety, shame, embarrassment, guilt, pride, and envy.

- Cognitive dimension of body image: Assessed using measures of satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) with an individual’s body shape, size, weight, and functionality/competence.

- Open door test: Test whereby individuals are asked to open the door as wide as would be needed for them to fit through

- Tripartite influence model: Suggests that there are formative social factors that influence the development and maintenance of negative body image and disordered eating. (Thompson et al., 1999)

- Downward social comparison: When individuals either compare themselves to those who are worse off

- Upward social comparison: When individuals either compare themselves to those who are better off

- Eating disorders: Recognized mental disorders that are defined as abnormal eating habits resulting in insufficient or excessive consumption of food (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

- Bulimia nervosa: Disorder defined by bingeing (i.e., recurrent excessive eating) and purging through self-induced vomiting, laxative/diuretic use, and/or excessive exercise.

- Anorexia nervosa: A disorder characterized by major restriction in food intake, heightened fear of gaining weight, and unrealistic perception of current body weight.

- Binge eating disorder: A disorder characterized as compulsive and excessive overeating without purging (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

- Normative Discontent: The idea that many individuals identify at least one aspect of their body appearance or functionality that they would like to change.

- Muscle dysmorphia: A specified condition within body dysmorphic disorder; defined as a chronic preoccupation with insufficient muscularity and inadequate muscle mass (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

- Physical self-concept: A hierarchical construct comprising descriptions specific to physical activity and sport competence, and appearance and weight.