4 Argumentation and Practical Reasoning in Family Policy

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Recognize the significance of critical thinking and reasoning for assessing and evaluating arguments, and utilize these skills to analyze family policies.

- Identify and distinguish the key components of an argument.

- Recognize and evaluate arguments and non-arguments within the context of family policy.

- Identify and steer clear of common logical fallacies and cognitive biases in arguments.

- Implement strategies to construct persuasive arguments, utilizing clear premises and conclusions, reliable evidence, and sound logic.

- Describe and apply the practical reasoning process to underpin policy recommendations.

- Cultivate skills in addressing counterarguments and limitations in family policy through evidence-based responses, ethical considerations, and practical implications.

- Collaborate with peers to construct and analyze persuasive arguments related to real-world family policy issues, demonstrating proficiency in applying the principles of argumentation and practical reasoning.

5.1 Building Persuasive Arguments

Critical Thinking and Reasoning

Critical thinking is essential in assessing and evaluating arguments for several reasons.

- Objective Assessment

-

- Critical thinking helps evaluate arguments without bias or preconceived notions.

- It enables fair evaluation based on facts and logic rather than emotions or personal beliefs.

- Objectivity is crucial in reaching sound conclusions (McLaughlin, 2023).

- Identifying Flaws

-

- Critical thinkers can recognize logical fallacies, inconsistencies, and biases in arguments.

- By identifying these flaws, they discern whether an argument is built on a solid foundation or flawed due to poor reasoning or misleading information (McLaughlin, 2023).

- Evaluating Evidence

-

- Critical thinking involves scrutinizing the quality, relevance, and source of the evidence supporting an argument.

- This includes considering the credibility of sources, research methodology, and data context.

- High-quality evidence strengthens an argument, while poor-quality evidence undermines it (McLaughlin, 2023).

- Understanding Complexity

-

- Many issues, especially in policy evaluation, are complex and multidimensional.

- Critical thinking helps appreciate this complexity, recognize various perspectives, and understand argument nuances.

- A comprehensive understanding is vital for thorough evaluation (McLaughlin, 2023).

- Effective Problem-Solving and Decision-Making

-

- Critical thinking enables individuals to weigh different arguments, consider potential consequences, and make informed decisions.

- This is particularly important in policymaking, where decisions can have widespread and long-term impacts (McLaughlin, 2023).

- Flexibility and Openness

-

- Critical thinkers are open to changing their views if evidence and reason support doing so.

- This flexibility and willingness to consider alternative viewpoints are essential for the continuous evolution and improvement of ideas and policies (McLaughlin, 2023).

- Clear Communication

-

- Critical thinking aids in articulating thoughts clearly and logically.

- This enhances the quality of both the arguments one makes and the evaluation of others’ arguments.

- Clear communication is crucial for the effective exchange of ideas and reaching consensus (McLaughlin, 2023).

- Constructing Persuasive Arguments

-

- In debates and discussions, critical thinking helps construct strong, persuasive arguments and effectively counter opposing views.

- This ability is important in advocacy, negotiation, and any scenario where convincing others is key (McLaughlin, 2023).

- In-Depth Understanding

-

- Instead of accepting information at face value, critical thinkers delve deeper into the underlying principles and assumptions of arguments.

- This deep understanding is crucial for thorough assessment and evaluation (McLaughlin, 2023).

- Empowering Citizenship

-

- In a democratic society, critical thinking empowers individuals to evaluate political arguments, media messages, and public policies effectively.

- This informed evaluation is essential for responsible and engaged citizenship (McLaughlin, 2023).

In summary, critical thinking is indispensable for the rigorous and balanced evaluation of arguments. It ensures that conclusions and decisions are well-founded, rational, and justifiable.

Identifying Arguments and Non-Arguments

To critically think about arguments, we will define the following concepts: argument, premises, and conclusion (McLaughlin, 2023).

- Argument:

- In critical thinking, an argument isn’t a heated exchange or disagreement. Instead, it’s a set of statements or propositions aimed at persuading someone that a particular conclusion is true or valid.

- An argument is composed of two main parts: premises and a conclusion. The role of an argument is to provide evidence or reasons (through its premises) to support the truth of the conclusion.

- Premises:

- Premises are the statements or propositions in an argument that provide the support or evidence.

- They are the foundational assertions that are assumed or presented as true for the sake of the argument.

- The role of premises is to be the building blocks or reasons that lead logically to the argument’s conclusion. They are what the conclusion is based upon.

- Conclusion:

- The conclusion is the statement or proposition that the premises are intended to support or prove.

- It is the end point of the argument, what everything else is leading towards. The conclusion is what the argument is trying to convince someone to accept.

- In a well-structured argument, the conclusion should logically follow from the premises. If the premises are true and the argument is logically sound, then the conclusion ought to be true as well.

Here’s an example of a family argument related to spending too much money:

Argument: “We need to cut back on our spending because we are going over our budget every month.”

Premises:

-

- Our credit card bills have been increasing steadily over the past few months.

- We have been eating out at restaurants more frequently than we used to.

- We recently made several large purchases, including a new TV and a gaming console, which were not planned for in our budget.

- Our savings account balance has been decreasing, and we haven’t been able to contribute to it as much as we should.

Conclusion: Therefore, we must reduce our spending to stay within our budget and avoid financial difficulties.

In this example, the argument is that the family needs to cut back on their spending. The premises provide the evidence to support this conclusion:

- The first premise points out that the family’s credit card bills have been increasing, suggesting that they are spending more than they can afford.

- The second premise identifies a specific area where the family has been spending more money than usual: eating out at restaurants.

- The third premise highlights recent large purchases that were not accounted for in the family budget, further contributing to the overspending problem.

- The fourth premise indicates that the family’s savings are being depleted and that they are not able to save as much as they should, which is a concern for their financial well-being.

These premises together lead to the conclusion that the family must take action to reduce their spending and live within their means. The argument aims to persuade family members that, based on the evidence provided, curbing their spending is necessary to avoid financial problems and maintain a balanced budget. When critically analyzing an argument, one of the key tasks is to identify the premises and see if they logically and effectively lead to the conclusion. This involves assessing the truth of the premises and the validity of the logical connection between the premises and the conclusion. Understanding these terms is crucial for effective critical thinking and for evaluating the strength and validity of arguments.

Avoiding Common Logical Fallacies and Biases in Arguments

Recognizing and avoiding logical fallacies and cognitive biases is crucial for constructing sound arguments and engaging in rational discussions. A logical fallacy is a statement that seems to be true until you apply the rules of logic (Chapman, 2024). Then, you realize that it’s not. Logical fallacies can often be used to mislead people—to trick them into believing something they otherwise would not believe (Chapman, 2024). Logical fallacies are sometimes confused with cognitive biases, but they are not the same. A cognitive bias is a tendency to make decisions or take action in an illogical way, caused by our values, memory, socialization, and other personal attributes (Chapman, 2024). Now, let’s examine some of the most common fallacies and cognitive biases that people use:

Logical Fallacies (Chapman, 2024):

- Ad Hominem: This fallacy occurs when you attack someone personally rather than using logic to refute their argument. Instead, they’ll attack physical appearance, personal traits, or other irrelevant characteristics to criticize the other’s point of view. These attacks can also be leveled at institutions or groups. For example, “Barbara: We should review these data sets again just to be sure they’re accurate. Tim: I figured you would suggest that since you’re a bit slow when it comes to math.”

- Bandwagon: You are led to believe in an idea or proposition simply because it’s popular or has lots of support. But the fact that lots of people agree with something doesn’t make it true or right. Example: “We surveyed all the customers in the store and they all agreed that staying open 24 hours would be a great idea. We need to put together a 24-hour schedule as soon as possible.”

- Straw Man: This fallacy involves creating a false argument and then refuting it. The counterargument is then believed to be true. By misrepresenting an opposing position (and then knocking it down) your own preferred position appears stronger. Example: A local politician plans to expand the municipality’s cycle network and add several new speed cameras in densely populated areas. Their opponent says, “They want us all to give up driving forever. They’re punishing the honest car owners and commuters that help pay these politicians’ salaries.”

- False Dilemma/False Dichotomy: This fallacy misleads by presenting complex issues in terms of two inherently opposed sides. Instead of acknowledging that most (if not all) issues can be thought of on a spectrum of possibilities and stances, this fallacy asserts that there are only two mutually exclusive outcomes. Example: “We can either agree with Barbar’s plan or just let the project fail. There is no other option.”

- Slippery Slope: This argument relies on making you think that the worst that can happen will actually happen if you take a particular course of action. Example: “If we allow Susan to leave early, soon we’ll be giving everyone Friday afternoon off.” This kind of argument crops up often. However, you can see that it’s illogical to conclude that you will have to give absolutely everyone an afternoon off, every single week, just by allowing one employee to leave early one time.

- Circular Reasoning/Begging the Question: This fallacy occurs when an argument’s premises assume the truth of the conclusion, instead of supporting it. In other words, you assume without proof the stand/position, or a significant part of the stand, that is in question. For example, “Wool sweaters are superior to nylon jackets as fall attire because wool sweaters have the higher wool content.” This begs the question because the argument fails to explain why having a higher wool content makes a garment superior.

- Appeal to Ignorance/Burden of Proof (Argumentum ad Ignorantiam): This is a fallacy that occurs when someone argues that a conclusion is true because there is no evidence against it. This fallacy wrongly shifts the burden of proof away from the one making the claim. Example: “Since you haven’t been able to prove your innocence, I must assume you’re guilty.”

- Hasty Generalization: This fallacy occurs when someone draws expansive conclusions based on inadequate or insufficient evidence. In other words, they jump to conclusions about the validity of a proposition with some, but not enough, evidence to back it up, and overlook potential counterarguments. Example: Two members of my team have become more engaged employees after taking public speaking classes. That proves we should have mandatory public speaking classes for the whole company to improve employee engagement.

- Red Herring: This is a diversionary tactic that avoids the key issues, often by avoiding opposing arguments rather than addressing them. Example: “The level of mercury in seafood may be unsafe, but what will fishers do to support their families?” In this example, the author switches the discussion away from the safety of the food and talks instead about an economic issue, the livelihood of those catching fish. While one issue may affect the other, it does not mean we should ignore possible safety issues because of possible economic consequences to a few individuals.

- Appeal to Authority (Argumentum ad Verecundiam): This is where you rely on an “expert” source to form the basis of your argument. Example: “In a study designed by a famous academic to test the effects of pleasant imagery on motivation, employees were shown images of baby animals and beautiful nature scenes for their first five minutes at work.” Mentioning an academic tends to imply authority and expertise, and that your argument is backed up by rigorous research. But name-dropping alone is not enough to “prove” your case.

- Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc (After This, Therefore Because of This): This fallacy is a conclusion that assumes that if ‘A’ occurred after ‘B’ then ‘B’ must have caused ‘A’. Example: “I drank bottled water and now I am sick, so the water must have made me sick.”

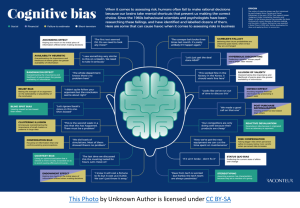

Cognitive Biases (Chapman, 2024):

- Actor-Observer Bias: This is the tendency to attribute your own actions to external causes while attributing other people’s behaviors to internal causes. For example, you attribute your high cholesterol level to genetics while you consider others to have a high level due to poor diet and lack of exercise.

- Anchoring Bias: This is the tendency to rely too heavily on the very first piece of information you learn. For example, if you learn the average price for a car is a certain value, you will think any amount below that is a good deal, perhaps not searching for better deals. You can use this bias to set the expectations of others by putting the first information on the table for consideration.

- Attentional Bias: This is the tendency to pay attention to some things while simultaneously ignoring others. For example, when deciding on which car to buy, you may pay attention to the look and feel of the exterior and interior, but ignore the safety record and gas mileage.

- Availability Heuristic: Overestimating the importance of information that is readily available or memorable, rather than all relevant information.

- Bandwagon Effect: Believing something because many other people believe the same.

- Confirmation Bias: This is favoring information that conforms to your existing beliefs and discounting evidence that does not conform.

- False Consensus Effect: This is the tendency to overestimate how much other people agree with you.

- Halo Effect: Your overall impression of a person influences how you feel and think about their character. This especially applies to physical attractiveness influencing how you rate their other qualities.

- In-group Bias: Favoring people who belong to the same group as oneself.

- Misinformation Effect: This is the tendency for post-event information to interfere with the memory of the original event. It is easy to have your memory influenced by what you hear about the event from others. Knowledge of this effect has led to a mistrust of eyewitness information.

- Overconfidence Bias: Holding unrealistically positive views of oneself and one’s abilities.

- Self-Serving Bias: This is the tendency to blame external forces when bad things happen and give yourself credit when good things happen. For example, when you win a poker hand it is due to your skill at reading the other players and knowing the odds, while when you lose it is due to getting dealt a poor hand.

- Status Quo Bias: Preferring things to stay the same by doing nothing or by sticking with a decision made previously.

- Sunk Cost Fallacy: Continuing a behavior or endeavor as a result of previously invested resources (time, money, effort).

Awareness of these fallacies and biases is the first step in avoiding them in arguments and discussions, leading to more rational and constructive communication. Here are strategies to help you avoid logical fallacies in your thinking and writing (Chapman, 2024):

- Understand Common Fallacies: Familiarize yourself with the most common logical fallacies, such as straw man, ad hominem, false dichotomy, slippery slope, and appeal to authority. Knowing these can help you identify and avoid them in your reasoning.

- Strengthen Your Argument Structure: Ensure your arguments are well-structured, with clear premises leading logically to your conclusion. Avoid making leaps in logic that can’t be supported by your premises.

- Seek Reliable Evidence: Support your arguments with evidence from credible, unbiased sources. This helps ground your reasoning in facts rather than fallacious logic.

- Consider Counterarguments: Actively thinking about and addressing potential counterarguments to your position can help you refine your argument and avoid oversimplification or misrepresentation.

- Ask for Feedback: Other people can offer valuable perspectives on your arguments, potentially spotting fallacies you’ve overlooked.

Here are strategies to help you minimize cognitive biases (Chapman, 2024):

- Awareness of Biases: Just as with fallacies, the first step in avoiding cognitive biases is to know they exist. Familiarize yourself with common biases such as confirmation bias, availability heuristic, anchoring, and hindsight bias.

- Slow Down Your Thinking: Many cognitive biases arise from our brain’s ‘fast’ thinking processes, which are automatic and based on heuristics. By slowing down and engaging in ‘slow’ thinking, you can more critically evaluate information and your reactions to it.

- Seek Diverse Perspectives: Exposure to a range of viewpoints can challenge and mitigate your biases. It helps prevent the echo chamber effect that reinforces existing biases.

- Practice Reflective Thinking: Regular reflection on your decision-making processes and judgments can help you identify biases in your thinking. Keeping a journal or discussing your thoughts with others can facilitate this reflection.

- Implement Structured Decision-Making: Using structured methodologies for making decisions can help reduce the influence of biases. For example, using a pros and cons list, SWOT analysis, or decision matrices can impose a more objective framework on your decision-making.

- Check Your Emotions: Emotions can significantly impact our susceptibility to both logical fallacies and cognitive biases. Being aware of how your current emotional state might influence your thinking is crucial.

- Continuous Learning and Adaptation: Regularly engaging with new information, challenging your assumptions, and adapting your perspectives based on new evidence or arguments can help mitigate the effects of biases and fallacies.

- Use Critical Questions: Regularly question your assumptions, sources, and the completeness of your information. Ask yourself if you might be making a decision or forming an opinion based on incomplete information or biased reasoning.

By actively applying these strategies, you can significantly improve your critical thinking and reasoning abilities, making your arguments stronger and your decisions more objective and well-informed.

5.2 Using Practical Reasoning to Support Policy Recommendations

Why use the practical reasoning process to support policy recommendations? Using the practical reasoning process in supporting family policy recommendations brings several key benefits in a cohesive and integrated manner. First, it ensures policies are grounded in solid data and focused on solving specific problems, emphasizing evidence-based decision-making. This approach is inclusive, valuing diverse perspectives and upholding ethical principles, which is crucial for ensuring fairness and addressing various family needs. Additionally, practical reasoning offers flexibility, allowing policies to adapt to changing family dynamics while maintaining a holistic view of the multiple factors impacting families. Moreover, it considers the feasibility of policy implementation, including aspects like resource allocation and administrative capabilities. This integrated approach results in more effective, equitable, and comprehensive family policies.

.

Step 1: Identify the Problem

Problem: Many families are struggling to access affordable and quality childcare, which impacts their ability to work and provide for their children.

Step 2: Gather Information—Collect data and insights from various sources:

- Surveys and Interviews: Conduct surveys and interviews with parents to understand their challenges and needs regarding childcare.

- Statistical Data: Analyze demographic data, employment rates, and current childcare costs.

- Existing Policies: Review current local, state, and federal policies related to childcare to identify gaps and areas for improvement.

Step 3: Analyze Options—Consider various policy options using practical reasoning:

- Subsidies for Childcare: Providing financial assistance to low- and middle-income families to help cover the cost of childcare.

- Tax Credits: Offering tax credits to families to offset childcare expenses.

- Employer-Sponsored Childcare: Encouraging or mandating employers to provide on-site childcare or childcare assistance.

- Community-Based Programs: Supporting the development of community-based childcare centers with sliding scale fees.

Step 4: Evaluate Feasibility and Impact—Use practical reasoning to evaluate the feasibility and potential impact of each option:

- Subsidies: Practical reasoning suggests that direct financial assistance can immediately reduce the burden of childcare costs for families. However, it requires significant funding and efficient administration.

- Tax Credits: This option can provide financial relief but may not help families who need upfront assistance. It benefits those who can wait until tax season for reimbursement.

- Employer-Sponsored Childcare: Practical reasoning indicates that this could significantly help working parents, but not all employers have the resources to implement such programs.

- Community-Based Programs: This approach could address childcare needs at a local level and provide flexible solutions, but it requires community involvement and sustainable funding.

Step 5: Formulate Recommendations—Combine the most feasible and impactful elements into a comprehensive policy recommendation:

- Mixed Approach: Recommend a combination of subsidies and community-based programs to address immediate financial needs and create sustainable childcare options.

- Pilot Programs: Suggest implementing pilot programs in diverse communities to test the effectiveness and refine the policy before a broader rollout.

- Partnerships: Encourage partnerships between government, private sector, and non-profits to pool resources and expertise.

Step 6: Implementation and Monitoring—Outline a practical plan for implementation:

- Phased Implementation: Start with pilot programs and gradually expand based on success and feedback.

- Continuous Monitoring: Establish metrics and feedback mechanisms to monitor the policy’s effectiveness and make necessary adjustments.

Example Policy Recommendation

Policy Name: Childcare Access and Affordability Enhancement (CAAE) Program

Objective: To improve access to affordable, high-quality childcare for all families.

Key Components:

- Childcare Subsidies: Provide direct financial assistance to low- and middle-income families to cover childcare costs.

- Community-Based Childcare Centers: Support the development of community childcare centers with a sliding fee scale to accommodate families of varying incomes.

- Public-Private Partnerships: Encourage collaboration between government agencies, private businesses, and non-profit organizations to increase childcare options and resources.

- Pilot Programs: Implement pilot programs in selected communities to evaluate effectiveness and scalability.

Implementation Plan:

- Phase 1: Launch pilot programs in urban, suburban, and rural areas.

- Phase 2: Assess outcomes and gather feedback to refine the policy.

- Phase 3: Expand successful programs and provide ongoing support and monitoring.

Monitoring and Evaluation:

- Regularly review program metrics such as enrollment rates, satisfaction surveys, and cost-effectiveness.

- Adjust the policy based on data-driven insights and stakeholder feedback.

By using practical reasoning, policymakers can create a balanced and effective approach to improve childcare access and affordability, ensuring that the policy addresses the real needs and circumstances of families.

5.3a Addressing Counterarguments in a Family Policy

Addressing counterarguments in a family policy involves a thorough and respectful consideration of opposing views, and then methodically responding to them. Here is a general approach to how this can be done using the affordable childcare issue as an example:

- Acknowledgment and Understanding: Begin by clearly acknowledging the counterarguments. This demonstrates that you have considered different perspectives and understand the concerns of those who may disagree with the policy. For instance, if the policy is about increasing government funding for childcare, a counterargument might be the concern about increased government spending and potential tax implications.

- Evidence-Based Response: Respond to counterarguments with evidence-based information. For example, in addressing concerns about increased spending on childcare, you could cite research showing the long-term economic benefits of such investment. A study by the Economic Policy Institute states that investments in early childcare and education would yield significant economic returns through increased labor force participation, greater tax revenues, and reduced government spending in other areas (Gould, 2017).

- Ethical and Moral Considerations: Address any ethical or moral concerns raised in the counterarguments. If a counterargument involves the perceived inequity of providing government-funded childcare to certain groups, you could discuss the ethical principle of equity and the moral imperative to support vulnerable families, as argued by Whitehurst (2017) in his research on the societal benefits of early childhood education.

- Practical Implications and Feasibility: Discuss the practicality and feasibility of the policy in light of the counterarguments. For example, address concerns about the administrative complexity of implementing new childcare programs by referencing successful models in other regions or countries, as documented by the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER).

- Engage in Dialogue: Foster an ongoing dialogue with stakeholders who hold opposing views. This can lead to a more nuanced understanding of the policy’s potential impacts and may result in modifications that address some of the concerns raised.

- Balance and Compromise: Finally, it might be necessary to find a balance or a compromise. For instance, if the policy’s cost is a major concern, consider proposing a phased implementation or looking for alternative funding sources.

By following these steps, policymakers can constructively engage with counterarguments, strengthen the credibility of their policy recommendations, and work towards solutions that are more broadly acceptable and effective.

Case Study Analysis Activity: Identifying Counterarguments

Objective: Enhance students’ ability to identify potential counterarguments in policy proposals related to affordable childcare.

Instructions: You will work individually or in small groups to analyze the given case scenarios. For each scenario, you will identify potential counterarguments and briefly explain why these counterarguments might be raised.

Scenario 1: Increased Government Funding for Childcare

Description: The government proposes to increase funding for childcare programs to make them more affordable for low-income families. This includes subsidies and grants for childcare centers.

What are the possible counterarguments?

Scenario 2: Employer-Sponsored Childcare Programs

Description: A new policy mandates that all large employers must provide on-site childcare facilities or childcare subsidies for their employees.

What are the possible counterarguments?

Scenario 3: Tax Credits for Childcare Expenses

Description: A policy is introduced to provide tax credits to families for their child care expense, aimed at easing the financial burden on working parents.

What are the possible counterarguments?

Scenario 4: Community-Based Childcare Initiatives

Description: The government supports the creation of community-based childcare centers that operate on a sliding fee scale to accommodate families of different income levels.

What are the possible counterarguments?

Scenario 5: Universal Pre-K Program

Description: A policy is introduced to provide free universal pre-kindergarten education to all children aged 3-4 years.

What are the possible counterarguments?

Discussion and Reflection

Task: After identifying counterarguments for each scenario, discuss as a class or in groups the validity of these counterarguments and how policymakers might address them. Reflect on how understanding and addressing counterarguments can lead to more robust and widely accepted policies.

5.3b Addressing Limitations in a Family Policy

Addressing limitations in a family policy involves recognizing and acknowledging these limitations, and then taking steps to mitigate them. Here is a structured approach to how this can be done using the affordable childcare issue as an example:

- Transparent Acknowledgment: Start by transparently acknowledging the limitations of the policy. For instance, if a policy focuses on increasing childcare facilities, acknowledge that it may not directly address issues like the quality of childcare or the unique needs of children with disabilities.

- Use of Evidence and Research: Reference relevant research to understand and contextualize these limitations. For example, a study by Bustamante et al. (2021) highlights that while increasing childcare facilities is beneficial, the quality of these facilities significantly impacts children’s developmental outcomes. Citing such studies can help in understanding the depth of the limitations.

- Stakeholder Consultation: Engage with stakeholders — parents, childcare providers, and child development experts — to gather insights on the policy’s limitations. This direct feedback can be invaluable in addressing specific concerns and improving the policy’s effectiveness.

- Adaptability and Flexibility in Policy Design: Design the policy to be adaptable, allowing for adjustments as limitations become more apparent or as new challenges arise. For instance, a policy might initially focus on increasing the number of childcare centers, but could later incorporate standards for quality and inclusivity.

- Pilot Programs and Phased Implementation: Implement pilot programs or a phased approach to test the policy on a smaller scale before full implementation. This strategy, recommended by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2020), allows for the identification and addressing of unforeseen limitations.

- Continuous Evaluation and Improvement: Establish mechanisms for ongoing evaluation and improvement of the policy. Regular monitoring and assessment can help in identifying limitations early and adjusting the policy accordingly.

- Resource Allocation for Overcoming Limitations: Allocate resources specifically for addressing the limitations. If funding is a limitation, for example, the policy could include strategies for diversified funding sources.

- Collaboration and Partnerships: Collaborate with other organizations and sectors to address limitations. Partnerships can bring in additional expertise, resources, and perspectives that can help overcome specific shortcomings of the policy.

By acknowledging limitations, using evidence to understand them, engaging stakeholders, designing adaptable policies, implementing pilot programs, continuously evaluating, allocating appropriate resources, and collaborating with partners, policymakers can effectively address and mitigate the limitations of family policies.

Activity: The Art of Persuasion: Building and Analyzing Arguments

Objective: You will learn how to construct persuasive arguments, identify the structure of arguments, use practical reasoning in policy recommendations, address counterarguments, and acknowledge policy limitations. This activity not only helps you understand the structure of arguments but also encourages you to engage critically with policy issues, think creatively about problem-solving, and appreciate the complexities of policymaking.

Part I: Understanding Arguments

- Individual Exercise: Using the concepts of arguments, premises, and conclusions provided in this chapter, identify which of the following statements are arguments and which are not, and for those that are, label the premises and conclusions.

Statement 1: Reducing pollution will improve public health because pollution is a major cause of health problems.

Is this an argument? (Yes/No): __________

Premises (if any): ______________________

Conclusion (if any): ____________________

Statement 2: Many people believe that a college education is essential for a successful career.”

Is this an argument? (Yes/No): __________

Premises (if any): ______________________

Conclusion (if any): _________________

Statement 3: Since all humans are mortal and Socrates is a human, Socrates must be mortal.

Is this an argument? (Yes/No): __________

Premises (if any): ______________________

Conclusion (if any): ____________________

Statement 4: “Exercise is good for your health.”

Is this an argument? (Yes/No): __________

Premises (if any): ______________________

Conclusion (if any): ____________________

Statement 5: Government should invest more in renewable energy because it is sustainable and reduces dependence on fossil fuels.

Is this an argument? (Yes/No): __________

Premises (if any): ______________________

Conclusion (if any): ____________________

Statement 6: Chocolate is the best flavor of ice cream.

Is this an argument? (Yes/No): __________

Premises (if any): ______________________

Conclusion (if any): ____________________

Statement 7: If we do not address climate change now, future generations will face severe environmental challenges.

Is this an argument? (Yes/No): __________

Premises (if any): ______________________

Conclusion (if any): ____________________

Statement 8: Unemployment rates have dropped in the last quarter, according to recent economic reports.

Is this an argument? (Yes/No): __________

Premises (if any): ______________________

Conclusion (if any): ____________________

2. Reflection: After completing this exercise, write a brief reflection on how you distinguished between arguments and non-arguments and how you identified the premises and conclusions in the statements provided.

Part II: Constructing a Persuasive Argument

- Group Activity: You or the PIT will construct an argument supporting a specific policy recommendation using the practical reasoning process.

- Presentation: You will present your arguments. The class will discuss the strengths and weaknesses of each argument.

Part III: Addressing Counterarguments

- Interactive Session: You will present a common counterargument related to your family issue. You or the PIT will discuss and note how you would address these counterarguments.

- Group Feedback: Each individual or PIT shares its strategies, and the class votes on the most effective responses.

Part IV: Acknowledging and Addressing Limitations

- Discussion: The instructor will lead a discussion on the importance of acknowledging limitations in policy arguments, using the affordable childcare policy as an example.

- Group Task: Each individual or PIT lists potential limitations of the proposed policy and suggests ways to mitigate them.

Part V: Reflection and Debrief

- Individual Reflection: You or the PIT will write a short reflection on what you learned about building and analyzing arguments.

- Group Debrief: We will discuss as a class what was learned and how these skills apply in real-world scenarios, especially in policymaking.

Criteria:

- Participation in group activities

- Quality of the constructed argument and counterargument responses

- Reflection piece on the learning experience

References

Bustamante, A. S., Dearing, E., Zachrisson, H. D., Vandell, D. L., & Hirsh-Paske, K. (2021). High-quality early childcare and education: The gift that lasts a lifetime. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/high-quality-early-child-care-and-education-the-gift-that-lasts-a-lifetime/

Chapman, A. (2024). Thinking better: Logical fallacies, cognitive biases, and how to avoid them. The Autodidact’s Toolkit.

Gould, E. (2017). What does good child care reform look like? Economic Policy Institute Report on Early Child Care and Education. https://www.epi.org/publication/what-does-good-child-care-reform-look-like/

McLaughlin, J. (2023). How to critically think: A concise guide. Broadview Press.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). How can governments leverage policy evaluation to improve evidence informed policy making? https://www.oecd.org/gov/policy-evaluation-comparative-study-highlights.pdf

Whitehurst, G. J. (2017). Why the federal government should subsidize childcare and how to pay for it. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-the-federal-government-should-subsidize-childcare-and-how-to-pay-for-it/