5 Teaching and Learning Processes: Designing Learning Experiences

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to:

- Analyze how social, political, economic, and institutional contexts shape curriculum design and instructional planning in Family and Consumer Sciences (FCS) environments.

- Compare and contrast technical (empirical rational) and practical reasoning (critical science) perspectives, focusing on their implications for teaching strategies, educator roles, and learner engagement.

- Apply the phases of the Practical Reasoning Framework to identify, analyze, and address real-world problems impacting individuals, families, and society.

- Design instructional experiences that position learners as active participants, co-creators of knowledge, and critical thinkers who engage collaboratively to solve problems.

- Utilize cooperative learning models, such as the Jigsaw Method and Socratic Seminar, to promote critical dialogue, cross-cultural understanding, and process skill development in diverse learning environments.

- Create learning plans that bridge classroom content with real-world applications, fostering learners’ ability to transfer knowledge and skills to personal, community, and societal contexts.

- Develop assessment tools that evaluate both content knowledge and process skills, such as communication, leadership, and critical thinking, emphasizing learners’ ability to apply their learning in authentic contexts.

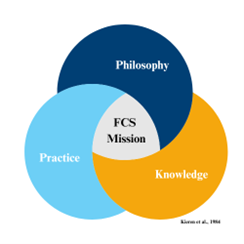

The practice of FCS environments focuses on cultivating a community of learners who collaboratively examine recurring issues, aiming to find ethical solutions and promote socially responsible actions that benefit both individuals and society (Laster & Johnson, 1998). To achieve this, teaching and learning experiences are learner-centered and process-driven, emphasizing strategies that foster cooperative learning and the development of practical reasoning skills.

Educator Philosophy: Practice

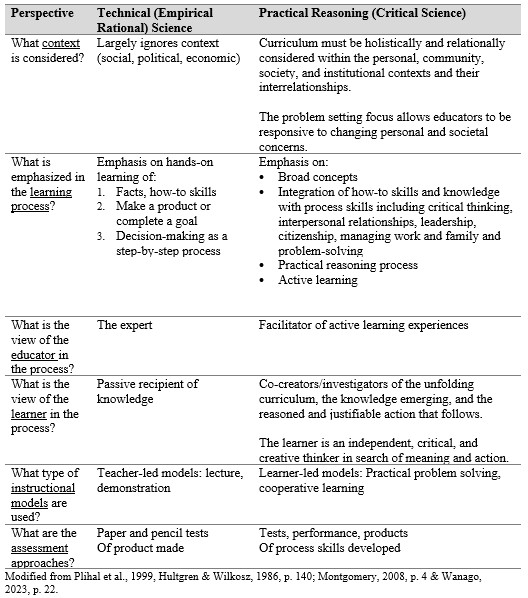

When educators design teaching and learning experiences through a practical reasoning (critical science) perspective, they utilize a set of beliefs about the roles of educators, learners, and context. These beliefs guide the processes used in creating instructional plans.

Learner-Centered: Role of Learner & Educator

FCS instruction aims to empower learners to develop the thinking and process skills necessary to determine what is ‘best’ when addressing practical problems. Learners are viewed as independent, critical, and creative thinkers who can actively engage in their own learning (Brown, 1980). They are seen as co-investigators in the learning process, sharing their expertise while taking responsibility for what they know, what they do, and how they interact with diverse individuals (Williams, 1999).

The curriculum content is learner-centered, evolving from active learner engagement to identify relevant problems and contextualizing the knowledge and processes needed to address these issues. In such learner-centered instructional environments, educators serve as facilitators, creating spaces where learners are encouraged to critically reflect on their knowledge, actions, and interactions with diverse individuals (Williams, 1999). A defining feature of this environment is that it is both challenging and democratic, encouraging learners to become active citizens who engage in critical dialogue about social forces, such as family policies, to improve the human condition (Laster & Johnson, 1998).

Contextual Teaching and Learning Models

Contextual teaching and learning help bridge the gap between educational experiences and real-world applications, connecting what is learned in school to the lived experiences of learners within their families, workplaces, communities, and the broader world (Smith, 2010). Within FCS environments, two main types of learner-centered contextual teaching and learning processes are employed: practical reasoning and cooperative learning.

Practical Reasoning

A central focus of FCS instruction is the development of practical reasoning skills, empowering learners to address challenges autonomously and proactively while positively contributing to their families and society (Hultgren & Wilkosz, 1986). The Practical Reasoning Framework, as described in Chapter 3, emphasizes instructional strategies that help learners develop and apply critical literacy skills, enabling them to determine “what ought to be” when exploring value-related problems (Montgomery, 1999).

Although the practical reasoning process is iterative, it offers an effective sequence for organizing courses, units, or lesson plans (Rehm, 2021). FCS environments value multiple forms of knowledge, and the Systems of Action framework provides guidance on which instructional strategies are most effective for developing the knowledge and skills required at each stage of practical reasoning (Fox & Laster, 2000; Montgomery, 2008). Each type of inquiry within the framework is associated with a different action (learner outcome) embedded throughout the practical reasoning process:

- Interpretive/Communicative: Learners develop the ability to share ideas, understand diverse perspectives on a problem, and anticipate the impact of actions on themselves and others.

- Reflective/Emancipatory: Learners critically examine the root causes of a problem and determine the best course of action for themselves, others, and society.

- Technical: Learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to understand information and perform tasks.

Analyzing each phase of practical reasoning alongside the Systems of Action Framework reveals key instructional strategies in Family and Consumer Sciences (FCS) that support the development of critical literacy skills.

Phase 1: Problem Identification and Awareness

- Instructional focus: Learners are introduced to or identify a problem by exploring its critical realities and how it impacts personal and social conditions (Rehm, 1999).

- Sample instructional strategies:

- Case studies: Present real-world examples that illustrate specific problems.

- Media: Encourage learners to research and synthesize news articles, videos, or reports related to the problem.

- Brainstorming: Engage learners in group sessions to brainstorm potential problems observed in their environment.

- Guest speakers: Invite community professionals to discuss the practical problems affecting individuals they serve.

- KWL charts: Have learners outline what they know about the problem, what they want to know, and what they learn after exploring the issue.

- Digital storytelling: Ask learners to create stories that showcase the problem’s impact on individuals and communities.

Phase 2: Develop Critical Consciousness

- Instructional focus: In this phase, learners develop an understanding and critique of the current state of affairs (“what is”) and explore “what ought to be.” Critical consciousness emerges as learners recognize the complex social environments and diverse personal and societal values that may perpetuate inequities (Plihal et al., 1999; Rehm, 1999). Dialogue and perspective-taking are essential in deepening this awareness (McGregor, 2003).

- Sample instructional strategies:

- Role play: Engage learners in scenarios where they adopt different roles to understand various perspectives.

- Interviews: Have learners conduct interviews to gain insights from multiple perspectives on the problem.

- Service-learning: Create opportunities for learners to engage in volunteer work or service-learning to enhance their understanding of the problem’s impact.

- Critical incident analysis: Analyze incidents that highlight ethical dilemmas or inequities related to the problem.

Phase 3: Analyze the Personal Context

- Instructional focus: This phase emphasizes the development of critical consciousness through cultural humility, where learners critically assess how their strengths, biases, beliefs, assumptions, and values shape their understanding and actions. In addition, this phase also fosters the development of knowledge and skills necessary for addressing the problem.

- Sample instructional strategies:

- Self-assessment tools: Use credible self-assessment tools to help learners uncover their strengths, personalities, and biases.

- Reflective journaling: Encourage learners to reflect on how their experiences relate to broader societal structures.

- Personal narratives: Have learners create stories that highlight their cultural background and experiences.

- Conceptual thinking: Use strategies that support conceptual thinking (i.e. concept-attainment, inductive reasoning, concept mapping) to support the development of shared understandings.

- New American Lecture: Deliver content that helps learners develop technical (how-to or factual) knowledge about the problem.

- Skill-building activities: Conduct labs or hands-on activities that develop the skills necessary for problem-solving.

- Scientific reasoning: Engage learners in scientific reasoning to teach factual content relevant to the problem.

Phase 4: Critique the External Context

- Instructional focus: Learners explore the broader setting of the problem, including historical, social, and political factors that contribute to its persistence. This phase enables learners to examine the problem’s complexity and consider how they can contribute to change (McGregor, 2003).

- Sample instructional strategies:

- Historical analysis: Research the issue’s historical background from various perspectives to understand its roots.

- Policy analysis: Guide learners in examining policies at local, state, and federal levels and proposing potential changes.

- Digital literacy: Support the development of digital literacy skills by critically assessing the reliability of information from various sources, including social media.

- Community mapping: Engage learners in mapping their communities to identify areas where social inequities exist and how these relate to broader societal issues.

Phase 5: Identify and Evaluate Alternatives and Consequences

- Instructional focus: Learners utilize their understanding from phases 2-4 to determine the desired outcome (“what should be”). They engage in divergent thinking to generate multiple potential solutions to the problem, and then critically evaluate both the short-term and long-term consequences, considering the impact on themselves and others. This process helps them make ethically and morally sound decisions for the benefit of all (Laster & Johnson, 1998).

- Sample instructional strategies:

- Brainstorming: Organize activities where learners generate as many options as possible before narrowing them down to a few alternatives for closer examination.

- Debates: Facilitate debates where learners argue for or against specific alternatives.

- Graphic organizers: Use tools such as cause/effect or problem/solution charts to help learners compare the consequences of various options.

- Decision-Making Models: Teach learners different decision-making models to help them determine which alternative is the best.

- Case comparisons: Provide case studies illustrating individuals affected by the problem. Learners work in small groups to assess the consequences of each alternative from the perspectives of those involved.

Phase 6: Take Action

- Instructional focus: A fundamental principle of the practical reasoning approach is collaboration for a common purpose (Brown, 1980). In this phase, learners formulate a plan to implement the chosen solution, using their process skills – communication, leadership, and management – to set goals and devise a course of action.

- Sample instructional strategies:

- Goal setting and action planning: Provide experiences that help learners develop their goal setting and action-planning skills.

- Pitch presentations: Have learners present their action plans to decision-makers to advocate for a potential change in a process.

- Advocacy letters: Develop learners writing skills to advocate for a social change using a strong rationale with evidence.

- Action research: Guide learners in conducting action research, allowing them to implement their plan and later reflect on its impact.

- Service learning: Encourage learners to collaborate with organizations to put their plans into action.

Cooperative Learning

To develop practical reasoning abilities, learning environments must offer safe, collaborative spaces where learners can engage in critical dialogue and learn from diverse perspectives. Cooperative learning is a key teaching strategy that shifts the focus from individual to group learning, making learners responsible not only for their own progress but also for supporting the learning of their peers (Slavin, 1995). Cooperative learning offers several key benefits:

- Process Skills: These strategies help develop social and intellectual skills vital to practical reasoning, such as communication, creative thinking, leadership, and management (Laster, 2001).

- Cross-Cultural Understanding: By working in teams, learners gain opportunities to foster cross-cultural awareness, respect differing viewpoints, and build interpersonal relationships (Johnson & Johnson, 1990).

- Group Functioning: Learners can reflect on their individual contributions to the group and explore ways to improve group dynamics by discussing what is working well and what isn’t (Johnson et al., 2014). These skills are directly transferable to family functioning.

In cooperative learning, learners are typically placed in small, heterogeneous groups of 4-5 members, working together to achieve a common goal (Allison & Rehm, 2007). The educator plays a crucial role in guiding the process, often by defining clear objectives, assigning roles, and facilitating dialogue to establish interaction guidelines. Common cooperative learning strategies include:

- Jigsaw Method: A topic is divided into sections, with each learner assigned to become an expert on one part. They then teach their section to the rest of the group. For instructions, go to Jigsaw: Developing Community and Disseminating Knowledge.

- Think-Pair-Share: The educator prompts an inquiry question. Learners first think or write about their response individually, then discuss with a partner or small group before sharing with the larger group. For instructions, go to Write, Pair, Share.

- Socratic Seminar: A democratic, learner centered approach to a class discussion where students meet in a circle to examine issues and values trough open-ended questions. For instructions, go to Designing Socratic Seminars to Ensure that All Students Can Participate.

The Questions Guide the Content

A key feature of the practical reasoning approach is that “content develops in response to the questions asked” (Smith, 2004, p. 50). The use of open-ended, critical questioning shapes classroom content by fostering learners’ abilities to think, reason, and reflect as they engage with authentic situations (Selbin, 1999). A learning environment driven by continuous question-asking creates a dynamic space that challenges learners to think critically and enhances their reasoning skills.

Regardless of the instructional strategy employed, both educators and learners must develop questions using each System of Action, as exploring the topic holistically using technical, interpretive and reflective knowledge is essential to examining the complexity of a problem. In learner-centered environments, the organization of questions—and subsequently the content—often begins with the communicative system of action. This system reveals how learners interpret problems, their values, and where shared meanings exist or diverge (Vincenti, 2002). Questions within the reflective system of action uncover repressive conditions and the consequences of decisions for both self and others when making judgments about what ought to be done. Meanwhile, technical questions define the skills and knowledge required to identify potential solutions. Organizing instruction to prioritize communicative and reflective systems first ensures that problems are examined with reasoned judgment, avoiding the temptation to seek habitual or quick fixes (Vincenti, 2002). Laster (2001) developed a list of question stems, also available to print, to inform questioning using each systems level.

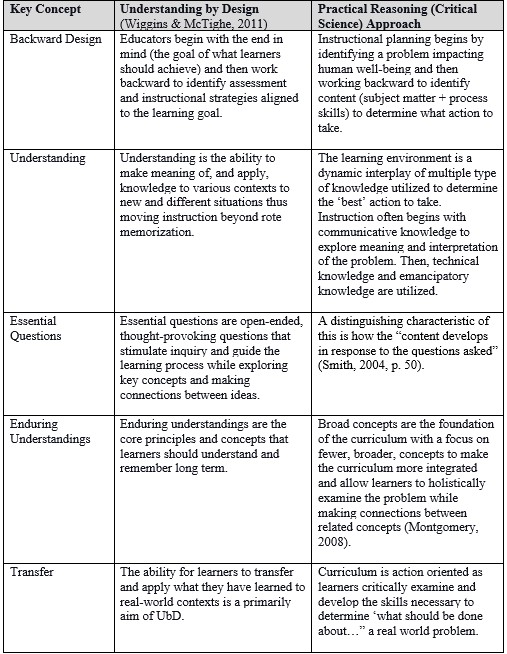

Creating Unit Plans: Understanding by Design

As educators create instructional plans to facilitate a problem-centered, process-oriented educational experience, the Understanding by Design (UbD) framework serves as an effective tool. Developed by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe, UbD—sometimes referred to as “backward design”—provides a three-stage planning process. This process guides educators in defining desired outcomes first and then working backward to develop the instructional plan (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011). The key concepts of the UbD framework closely align with the essential features of instruction rooted in a practical reasoning (critical science) approach, making it an effective planning tool for FCS educators (Laster & Johnson, 2001).

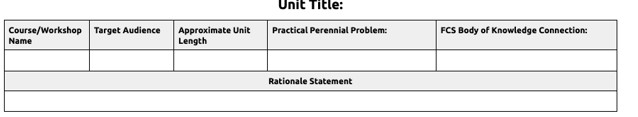

The Why: Connecting to the Profession & Practical Problems

When constructing a unit plan, it is crucial to start by articulating why the content is essential for your learners and how it connects to the FCS profession. In addition to logistical details such as the unit title, course or workshop name, target audience, and approximate length, the following elements should be clearly defined:

- Practical Problem: State the practical problem in terms of “what ought to be” or “what should be done” to address it.

- Body of Knowledge Connection: Explain how the practical problem relates to one or more components of the FCS Body of Knowledge, including core concepts, integrative elements, or cross-cutting themes (as described in Chapter 1).

- Rationale Statement: Educators utilizing the practical reasoning (critical science) approach must engage in reflective practice and personal critique, consciously examining their beliefs and how these influence educational decisions (Kister, 1999). A well-developed rationale statement allows educators to articulate “what” family problem to address and clarify “why” the problem is important to examine from a social perspective (Kister, 1999). Crafting a rationale not only strengthens program design but also emphasizes the distinctiveness of FCS instruction by defining the specific mode of inquiry (Kister, 1999). Data from the gap analysis often provides research-based content for the rationale.

Modified Understanding by Design (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011) template. Download the Family and Consumer Sciences UbD template.

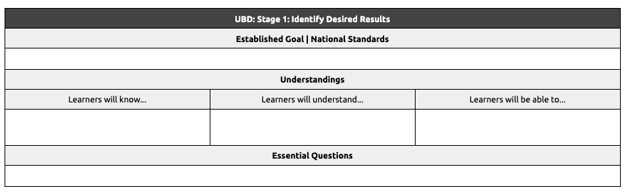

Stage 1: Identify Desired Results

One of the key benefits of the Understanding by Design (UbD) framework is its focus on alignment (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). This framework helps educators systematically connect learning goals with appropriate assessment tools and learner experiences that support those goals. The process begins by identifying the desired results:

- Establish Goal: Educators start by determining the goal they want learners to achieve (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011). In Family and Consumer Sciences, the goal is informed by the practical problem, with a focus on “what to do” or “what ought to be done” (Plihal et al., 1999). By conducting a gap analysis educators refine their goal by identifying the key gaps in knowledge or skills that contribute to the problem. The goal should relate to an FCS National Content or Comprehensive standard. Therefore, the goal may be a national standard (i.e. 14.1: Analyze factors that influence nutrition and wellness practices across the lifespan). Often a unit plan has a limited number, one to two, goals maximum to provide a clear and strong alignment between the goal, content, instructional strategies, and assessment methods.

- Identify Understandings: The next step is to break down the goal to pinpoint the types of knowledge and skills that should be prioritized when designing learning experiences and assessment tools. This ensures alignment between the desired goal and the learning process, while also emphasizing the transferability of learning across multiple contexts. Insights from the gap analysis highlight what learners need to develop or understand. The UbD framework includes three core elements:

- Know (the what): What content should learners know to address the problem? This may include technical knowledge (facts, critical details, processes, terminology) or communicative knowledge (meanings and interpretations). The knowledge is often the more discrete (specific) objectives that learners need to know (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011).

- Understand (the why): What are the long-term understandings learners need when addressing the problem? These understandings are often framed as the moral of the story to provide deeper meaning to the facts and help learners retain essential lessons for future application (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011). Understandings are stated as complete sentences and often integrate the broad concepts to make the curriculum more integrated and allow learners to holistically examine the problem while making connections between related concepts (Montgomery, 2008).

- Be able to do (the how): What skills or abilities should learners demonstrate to address the problem? These may be task-oriented (how to complete something) or process-oriented (intellectual and social skills).

- Create Essential Questions: Essential questions are open-ended and provocative, designed to foster inquiry and help learners uncover important ideas or concepts (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011). In the context of Family and Consumer Sciences, FCS Process Questions can serve as a starting point for creating essential questions that focus on thinking, communication, leadership, and management, while integrating technical, communicative, and reflective knowledge.

Modified Understanding by Design (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011) template. Download the Family and Consumer Sciences UbD template.

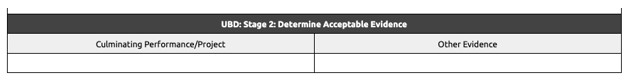

Stage 2: Assessment Evidence

Assessment evidence in the UbD framework includes the identification of a collection of evidence to determine if the different knowledge, understandings and skills have been developed in relationship to the overall goal. Because the focus of UbD is the ability to apply, and transfer, knowledge to real-world situations, assessment evidence typically includes a culminating product or performance (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011).

The same principles guide assessment priorities when designing curriculum informed by the practical reasoning (critical science) approach. Assessments focus on the subject matter content and the process skills developed using a collection of tools to explore both knowledge (e.g., tests, worksheets) and a learner’s ability to apply and demonstrate their skills in authentic contexts (e.g., performances and products). Because the practical reasoning approach emphasizes critical literacy skill development to engage in reasoning processes, assessment may also include the learner’s ability to identify problems impacting the family and ask critically reflective questions to understand and critique the issue (Olsen et al., 1999). In addition, because the FCS content includes process skills and is often facilitated in cooperative learning environments, group processes should be considered as a component of the collection of assessment evidence (Olsen et al., 1999).

When identifying the collection of evidence, educators should begin by identifying their real-world culminating product or performance that holistically addresses the overall unit goal. Then, the collection of other evidence is a list of multiple strategies to assess each of the knowledge and skills identified in stage one has been learned.

Modified Understanding by Design (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011) template. Download the Family and Consumer Sciences UbD template.

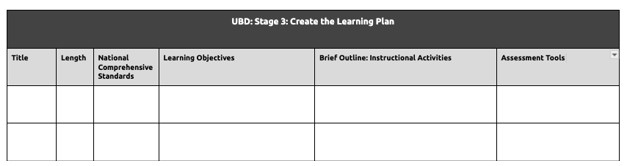

Stage 3: Learning Plan

In Stage 3, educators continue the backward design process by creating a logical sequence of instruction that facilitates learning of the core topics identified in Stage 1. This sequence is intended to equip learners for the culminating product or performance outlined in Stage 2 (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011).

To organize the learning plan, educators break the knowledge and skills into manageable chunks. These chunks become individual lesson plans within the overall unit. When arranging these into a logical instructional sequence, consider the following approaches:

- Increasing Complexity: Start with foundational concepts and gradually move to more complex ideas. For example, in a unit on nutrients, begin with an overview of basic nutrient principles, then progress to in-depth lessons on specific nutrients, and finally, apply the content in a real-world context, such as a case study.

- Communicative Understanding: Start by developing a shared, communicative understanding of a key term (e.g., “family”) or a broad concept (e.g., “responsibility”). Then, move on to lesson plans that integrate communicative, technical, and reflective knowledge, culminating in a final product or performance tied to the unit goal.

- Theory or Framework: Theories and frameworks help organize and explain concepts, showing connections and fostering understanding of a phenomenon. For example, the Practical Reasoning Framework is an effective tool for structuring instruction. Each lesson plan can emphasize a phase of practical reasoning, progressing through the six phases—from problem identification to taking action, which serves as the culminating performance. Alternatively, using a foundational theory like Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977), lessons could start with understanding the impact of a problem on the individual, then move through the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem, before completing the culminating performance.

Once the content’s organizational structure is established, educators outline the specific teaching and learning experiences within individual lesson plans or workshops. This stage begins to detail the instructional strategies and assessment tools that will support the unit’s goals. Learning plan elements include:

- Title: The lesson plan or workshop title.

- Length: The anticipated length of the lesson plan or workshop.

- National Comprehensive Standards: These standards serve as measurable indicators of knowledge and skills. Typically, the standards chosen align with the learning goal (e.g., content standard 4.1 for the goal and comprehensive standard 4.1.3 for the lesson plan) to ensure alignment.

- Learning Objectives: Each lesson plan typically has 1-5 learning objectives. These are specific, measurable statements that define what learners should know and be able to do by the end of the lesson. The objectives should be organized to reflect the knowledge, understanding, and skills identified in Stage 1.

- Instructional Activities: This section provides an outline of the learning activities, with an emphasis on instructional strategies designed to meet the learning objectives. Strategies should vary to address different learning styles and needs while aligning with the core principles of FCS instruction—fostering both subject matter knowledge and process skill development.

- Assessment Tools: Lesson plans usually include a collection of assessment evidence. The assessments should align with those identified as “other evidence” in Stage 2 and ensure that each lesson objective is evaluated during instruction. The final lesson often serves as the culminating performance, which holistically assesses the learning across all lesson plans in relation to the unit goal.

This systematic approach ensures that learners are fully prepared to demonstrate their understanding and skills in meaningful, authentic ways.

References

Allison, B.N., & Rehm, M.L. (2007). Teaching strategies for diverse learners in FCS classrooms. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 99(2), 8-10.

Brown, M. M. (1980). What is home economics education? University of Minnesota, Minnesota Research and Development Center for Vocational Education.

Fox, W.S., & Laster, J.F. (2000). Reasoning for action. In A. Vail, W. Fox, & P. Wild (Eds.), Leadership for Change: National Standards for Family & Consumer Sciences- Yearbook 20 (pp. 20-33). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Hultgren, F., & Wilkosz, J. (1986). Human goals and critical realities: A practical problem framework for developing home economics curriculum. Journal of Vocational Home Economics Education, 4(2), 135-154.

Johnson, D. W. & Johnson, R.T. (1990). Social skills for successful group work. Educational Leadership, 47(4), 29-33.

Johnson, D. W., Jonson R.T., & Smith, K.A. (2014). Cooperative learning: Improving university instruction by basing practice on validated theory. Journal of Excellence in College Teaching, 25(3-4), 85-118.

Kister, J. (1999). Forming a rationale: Considering beliefs, meanings and context. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 45-57). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Laster, J. F., & Johnson, J. (2001). Major trends in Family and Consumer Sciences. In S SS. Redick, A. Vail, B. P. Smith, R. G. Thomas, P. Copa, C. Mileham, C. Fedje, & K. Alexander (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences: A chapter of the curriculum handbook. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

Laster, J. (2001). Chapter 7: Principles of teaching practice in family and consumer sciences education (pp. 63-87). Curriculum Handbook published by the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2003). Critical science approach – A primer. Kappa Omicron Nu FORUM, 15(1). https://publications.kon.org/archives/forum/forum15-1.html

Montgomery, B. (1999). Continuing concerns of individuals and families. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 80-90). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Montgomery, B. (2008). Curriculum development: A critical science perspective. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 26(National Teacher Standards 3), 1-16.

Olson, K., Bartruff, J., Mberengwa, L., & Johnson, J. (1999). Assessment: Using a critical science approach. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 208-223). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Plihal, J., Laird, M., & Rehm, M. (1999). Chapter 1: The meaning of curriculum: Alternative perspectives. In J. Johnson & C. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: Toward a critical science approach. Teacher Education Yearbook 19, 2-22. American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences.

Rehm, M. (1999). Learning a new language. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 58-69). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Rehm, M. (2021). The critical science approach: Perennial problems, practical reasoning, and developing critical thinking skills. In K. Alexander & A. Holland (Eds.), Teaching Family and Consumer Sciences in the 21st Century (3rd ed.). The Curriculum Center for Family and Consumer Sciences.

Selbin, S. (1999). Developing questions in critical science. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 167-173). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Slavin, R. E. (1995). Cooperative learning: Theory, research, and practice. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Smith, B. P. (2004). FCS curriculum development and the critical science perspective. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 96(1), 49-51.

Smith, B.P. (2010). Instructional strategies in Family and Consumer Sciences: Implementing the contextual teaching and learning pedagogical model. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences Education, 28(1), 23-38.

Vincenti, V. B. (2002). Addressing problems effectively using critical science. American Home Economics Association.

Wanago, N. C., (2023). A Qualitative Exploration of the Home Economics/Family and Consumer Sciences Professions Critical Science Paradigm Shift [Doctoral dissertation, Texas Tech University]. Texas Tech Repository. https://ttu-ir.tdl.org/items/65ad1ae5-13a2-472c-9db8-cced204a8859

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2011). The understanding by design guide to creating high quality units. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Williams, S. K. (1999). Critical science curriculum: Reaching the learner. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 70-79). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.