3 Practical Reasoning in Family and Consumer Sciences/Human Sciences Curriculum

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to:

- Define curriculum and explain its key components, including philosophy, goals, objectives, learning experiences, instructional resources, and assessments, within the context of FCS/human sciences education.

- Analyze and compare prominent curriculum design models—subject-centered, learner-centered, and problem-centered—with the practical reasoning perspective, emphasizing their strengths, limitations, and applications.

- Apply the Family & Consumer Sciences Body of Knowledge (FCS-BOK) and practical reasoning framework to develop curricula that address immediate and perennial issues impacting individuals, families, and communities.

- Develop strategies to integrate the Reasoning for Action standard and process questions into FCS/human sciences curricula to promote critical thinking, ethical decision-making, and action-oriented learning.

- Design practical reasoning-based curriculum content that incorporates technical, interpretive/communicative, and reflective systems of action to enhance student engagement and learning outcomes.

- Employ community-based advisory committees, gap analyses, and broad concepts with long-term value to identify and address emerging issues and perennial concerns in curriculum development

- Evaluate the effectiveness of a practical reasoning-based curriculum through systematic assessments of learner progress, instructional materials, and alignment with FCS national standards.

There is no universally accepted definition of curriculum (Gordon, Taylor, & Olivia, 2019). However, curriculum should be understood as a structured process that outlines the philosophy, goals, objectives, learning experiences, instructional resources, and assessments comprising a specific educational program (Gordon, Taylor, & Olivia, 2019). Additionally, it provides teachers, learners, administrators, and community stakeholders with a measurable plan and framework for delivering quality education.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide guidance on developing a FCS/Human Sciences curriculum that incorporates a practical reasoning perspective. Effective curricula should be structured around the mission and knowledge base (content) foundational to the human sciences field. Brown and Paolucci (1979) articulated the following mission statement for Home Economics, now known as Family & Consumer Sciences (FCS):

“This mission of home economics is to enable families, both as individual units and generally as a social institution, to build and maintain systems of action which lead (1) to maturing in individual self-formation and (2) to enlightened, cooperative participation in the critique and formulation of social goals and means for accomplishing them” (p. 23).

The knowledge base developed to accomplish this mission is the Family & Consumer Sciences Body of Knowledge (FCS-BOK) (Nickols et al., 2009). One of the purposes of the FCS-BOK is to frame curricula that address both immediate and perennial problems (Nickols et al., 2009). Using the FCS-BOK as a framework enables FCS professionals to develop curricula that “…adequately reflect and confront the rapidly changing and increasingly complex social conditions encountered by individuals and families” (Plihal, Laird, & Rehm, 1999).

This chapter will:

- Compare prominent curriculum designs with the practical reasoning perspective;

- Discuss strategies for integrating the FCS-BOK into the curriculum;

- Explore methods for incorporating the practical reasoning perspective into curriculum development; and

- Describe the importance of conducting effective evaluations for a practical reasoning-based curriculum.

Comparison of Curriculum Designs to the Practical Reasoning Perspective

In today’s educational systems, three prominent models of curriculum design are subject-centered, learner-centered, and problem-centered (Wiles & Bondi, 2019).

Subject-Centered Curriculum Design

The subject-centered curriculum design revolves around a specific subject matter or discipline, with minimal emphasis on cross-curricular connections (Wiles & Bondi, 2019). This design is the most prevalent in schools today, largely due to its alignment with the standards-based movement (Wiles & Bondi, 2019). Its primary purpose is to ensure learners achieve mastery of content knowledge, leaving no gaps in what is taught (Wiles & Bondi, 2019). In this approach, educators present content and skills to learners in a logical, step-by-step sequence, ensuring they gain the information and skills necessary to master the subject matter (Wiles & Bondi, 2019).

Strong emphasis is placed on instruction, teacher-to-student explanations, and direct teaching strategies such as lectures, question-and-answer sessions, and discussions. This design often relies on memorization and repetitive practice of facts and concepts. Criticisms of the subject-centered design include:

- It is not learner-centered,

- It focuses on knowledge rather than skills, and

- It inadequately prepares learners for the complexities of adult working life (Wiles & Bondi, 2019).

Learner-Centered Curriculum Design

The learner-centered curriculum design focuses on the needs, interests, and goals of the learner (Wiles & Bondi, 2019). This approach empowers learners to make decisions about their learning, fostering engagement and motivation. Differentiation is a key feature, enabling learners to select assignments, learning experiences, or activities that are both timely and relevant (Wiles & Bondi, 2019).

However, this approach can be labor-intensive for educators and may be impractical in schools with large class sizes. Balancing learners’ wants and interests with their needs and required outcomes can also pose challenges (Wiles & Bondi, 2019). Despite these drawbacks, the learner-centered design has been shown to create more engaging and personalized learning environments.

Problem-Centered Curriculum Design

The problem-centered curriculum design teaches learners to analyze situations and develop solutions (Wiles & Bondi, 2019). This approach connects learning to real-world issues, fostering authenticity and the transfer of skills to everyday life. Educators encourage learners to draw on their own experiences to find solutions, making the curriculum highly relevant.

Problem-centered design has been shown to promote creativity, innovation, collaboration, and critical thinking. It enhances problem-solving and communication skills while encouraging lifelong learning (Wiles & Bondi, 2019). However, this approach may not always account for individual learner needs and interests, and it often lacks integration with industry or community mentors who could support the development of real-world solutions (Wiles & Bondi, 2019).

Distinction Between Technical Science and Practical Reasoning Perspectives

All three curriculum designs primarily employ the technical science perspective, which focuses on “how” to organize, implement, and evaluate curricula (Plihal et al., 1999). The technical science perspective validates curriculum through scientifically proven methods, including purposeful definitions, observation, and measurement (Plihal et al., 1999). Its goal is to find the most effective and efficient means to achieve pre-determined, unexamined ends (Plihal et al., 1999).

In contrast, the practical reasoning perspective explores philosophical and ethical questions such as “What knowledge is of most worth?”, “Why?”, and “What ought to be?” (Plihal et al., 1999). This approach acknowledges the need for technical knowledge but also incorporates communicative, interpretive, and emancipatory knowledge to address the broader needs of individuals, families, and communities (Brown, 1980).

Curricula designed with the practical reasoning perspective focus on framing problematic situations, clarifying and justifying goals, and exploring multiple means to achieve those goals (Plihal et al., 1999). This approach embraces context, personal values, and ethics as essential components of the curriculum, offering a holistic view of the learning process.

Key distinctions between the two perspectives include:

- Contextual Consideration: While the technical science perspective largely ignores the context of curriculum, the practical reasoning perspective emphasizes the importance of personal and social contexts influencing the learning process.

- Role of Teachers and Learners: The technical science perspective views learners as passive recipients of knowledge provided by teachers as experts. Conversely, the practical reasoning perspective sees both learners and educators as active participants and contributors to the learning process (Plihal et al., 1999).

- Bias and Values: Technical science-based curricula aim to be bias- and value-free, while practical reasoning-based curricula embrace ethical and value-driven questions, such as “What action should be taken?” and “Why?” (Plihal et al., 1999).

The Importance of Practical Reasoning in Curriculum

FCS/Human sciences professionals must consider implementing a practical reasoning perspective to address the complex needs of individuals, families, and communities (Montgomery, 2008). This perspective equips learners to:

- Form conscious goals or valued ends,

- Interpret contextual information,

- Apply technical knowledge and skills,

- Evaluate alternative actions and consequences, and

- Make informed decisions about what action(s) to take (Brown & Paolucci, 1979).

Developing a practical reasoning-based curriculum involves researching recent issues and trends within the discipline at both state and national levels. This research enables FCS/human sciences professionals to identify critical topics and develop rigorous learning standards and competencies. By integrating the practical reasoning perspective, curricula can better prepare learners to navigate the complexities of modern society and take meaningful, ethical actions.

Family & Consumer Sciences (FCS) National Standards

The National Association of State Administrators of Family and Consumer Sciences (NASAFACS), now known as LEADFCS Education (2018), developed the first set of national FCS learning standards and core competencies in 1998, aligned with the Family and Consumer Sciences Body of Knowledge (FCS-BOK). These standards were updated in 2008 to reflect current expectations in the FCS profession and align with the federal Career Clusters™ initiative, which became increasingly prominent across states (LEADFCS Education, 2018). In 2018, the standards were revised again to provide a forward-looking vision and a structured framework for what learners should know and be able to do upon completing a sequence of courses within a defined career pathway or program of study.

The third iteration of the national FCS standards includes the following components (LEADFCS Education, 2018):

- 16 FCS Areas of Study aligned with the FCS-BOK, each containing comprehensive and content standards.

- Comprehensive Standards: Broad descriptions that help individuals understand the scope of each content area.

- Content Standards: Specific expectations outlining what individuals should know and be able to do upon completing a program of study or sequence of courses related to the FCS-BOK, skills, and practices.

- Competencies: Detailed definitions of what individuals need to know and do, framed with action verbs and designed to measure the knowledge, skills, and practices tied to the content standards.

- Process Questions: A practical reasoning component designed to guide critical thinking, reasoning, and reflection on content through the lens of contextual problem-solving.

The Reasoning for Action Standard

A key feature of these standards is the Reasoning for Action standard, which is described as “an overarching, process-oriented standard that delineates knowledge and skills for high-quality reasoning” (LEADFCS Education, 2008, p. 1). The associated process questions are organized around four process areas—Thinking, Communication, Leadership, and Management—and are provided for each content standard across the 16 Areas of Study (LEADFCS Education, 2008).

FCS/Human sciences professionals can use the Reasoning for Action standard and process questions as a foundational framework for curriculum development or integrate them into their teaching more subtly. These tools encourage learners to engage critically with content and develop actionable solutions to practical problems.

Source: What is FCS? https://www.aafcs.org/about/about-us/what-is-fcs/what-is-fcs-video

Applying LEADFCS Education Standards to a Practical Reasoning Problem

To demonstrate how the LEADFCS Education standards can be applied to a practical reasoning problem, consider the example of improving access to affordable childcare.

Context and Setup: Practical Reasoning Problem—Improving Access to Affordable Childcare

Step-by-Step Application:

- Identify Relevant FCS Areas of Study

Choose the FCS areas of study relevant to the issue. For affordable childcare, these might include Child Development/Guidance, Parenting Education, and Consumer and Family Resources. - Comprehensive Standards

Review the general descriptions provided by the comprehensive standards for the selected areas. For example, the Consumer and Family Resources standard may address family financial management, a critical aspect of managing childcare costs. - Content Standards

Identify the specific knowledge and skills learners are expected to acquire by the end of the program. For instance, in Parenting Education, content standards might include understanding the developmental impacts of various childcare options. - Competencies

Define specific, measurable competencies using action verbs. Examples include:- Analyze the financial impact of various childcare options on family budgets.

- Evaluate the quality of care provided by different childcare centers.

- Plan a family budget that incorporates affordable childcare solutions.

- Process Questions for Practical Reasoning

Use the process questions framework to guide critical thinking and reasoning. For example:- Thinking: What are the primary financial challenges families face in securing childcare? How can these challenges be mitigated?

- Communication: How can we effectively communicate the importance of affordable childcare to policymakers and the community?

- Leadership: What leadership roles can community members take to advocate for affordable childcare solutions?

- Management: How can families better manage their resources to accommodate childcare costs?

Example of Applying the Reasoning for Action Standard

Practical Reasoning Problem: Improving Access to Affordable Childcare

- Define the Problem

Affordable childcare is a pressing issue that affects family financial stability and workforce participation. - Gather Information

- Research current childcare costs, availability, and quality.

- Explore existing financial assistance programs and policies.

- Consider Options

- Evaluate childcare models, such as home-based, center-based, and cooperative options.

- Assess community-based and employer-supported childcare solutions.

- Make a Plan

- Develop a plan that includes budget management, applying for financial assistance, and selecting the most suitable childcare option.

- Take Action

- Implement the plan and monitor its effectiveness.

- Advocate for policy changes to support affordable childcare initiatives.

- Evaluate Results

- Assess the outcomes of the plan and identify areas for improvement.

- Reflect on successes and challenges to refine future strategies.

Benefits of Using LEADFCS Education Standards

- Structured Approach: Offers a clear framework for addressing practical problems systematically.

- Critical Thinking: Encourages learners to develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

- Actionable Steps: Translates knowledge into practical, real-world actions.

- Holistic Learning: Integrates diverse aspects of FCS education, fostering a comprehensive understanding and application.

By incorporating the LEADFCS Education standards and process questions, human sciences professionals can create curricula that equip learners with the tools and reasoning skills necessary to address real-world challenges effectively.

Strategies for Integrating the Practical Reasoning Approach in the FCS/Human Sciences Curriculum

Standard 7 of the FCS National Standards for Teacher Education

Standard 7 of the FCS National Standards for Teacher Education emphasizes that human sciences professionals should:

“Develop, justify, and implement course curricula in programs of study supported by research and theory that addresses perennial and evolving family, career, and community issues; reflect the critical, integrative nature of human sciences; integrate core academic areas; and reflect high-quality career and technical education practices” (National Association of Teacher Educators for Family and Consumer Sciences, 2018).

Updated Competencies Related to Standard 7

The competencies related to Standard 7 were recently updated to include the following (NATEFACS, 2020):

- Develop and justify curricular choices that meet the needs of all learners.

- Implement curricula that address recurring concerns and evolving family, consumer, career, and community issues.

- Design curricula that reflect the integrative nature of human sciences content.

- Integrate human sciences content and grade-level core academic standards.

Challenges of Implementation

Due to the interdisciplinary nature of the FCS/human sciences profession and the technical standards mandated by most states’ education agencies, incorporating the practical reasoning approach can be challenging—particularly for those without a teacher education background. Often overlooked is the fact that curriculum should always shape learners’ everyday experiences within a multicultural society (Baldwin, 1999). Implementing practical reasoning in FCS/human sciences curricula enables learners to engage in transformative learning processes. This empowers them to determine justifiable actions related to their own practical or moral problems, the issues within their future families, and societal challenges as a whole.

Aligning Curriculum with the Home Economics Mission

As previously mentioned, the mission and vision of Home Economics should always guide curriculum development using the practical reasoning approach. Consequently, FCS/human sciences curricula should center on broad, perennial practical problems affecting individuals, families, and communities. These include concepts for addressing such concerns and promoting ethical action (Laster, 2008).

For example, food insecurity can be addressed through questions like:

- “Why should people be concerned about food insecurity, its meaning, and ways of identifying it?”

- “What should society do about food deserts that increase food insecurity for families?”

- “What actions should individuals, families, and society take to address food insecurity concerns?”

Strategies for Developing a Practical Reasoning-Based Curriculum

1. Forming a Community-Based Advisory Committee

The first step in developing a practical reasoning-based curriculum is forming a community-based human sciences advisory committee. This committee should include parents, industry and community representatives, school personnel, and past and present learners to ensure a collaborative curriculum development process.

Members of the advisory committee should be open-minded, possess critical analysis and listening skills, and demonstrate creativity and a willingness to consider new ideas. As Laster (2008) explains, “When committee members become engaged in practical reasoning and reflective dialogue, a morally defensible family-focused curriculum is more likely to be developed” (p. 8).

Key questions for the advisory committee include:

- What recurring practical problems do individuals and families in our community face?

- Which concerns should our FCS program address in the next 5, 10, or 50 years?

- What content should be taught to prepare youth for these concerns?

- What resources are needed to address these issues in the learning environment?

Once the advisory committee establishes the framework, FCS/human sciences educators and learners can address evolving practical problems, continuously refining the curriculum through classroom planning.

2. Conducting a Gap Analysis and Developing a Rationale Statement

To ensure the curriculum meets learners’ needs, educators should conduct a gap analysis to determine “what is taught” versus “what should be taught” based on recurring or emerging community problems. After identifying gaps, educators can develop a rationale statement addressing:

- What perennial or emerging problem needs to be addressed?

- What are the consequences of addressing or not addressing this issue?

- What concepts will the program, course, or unit focus on?

- Why is it important for learners to understand these concepts?

A well-crafted rationale statement clarifies the philosophical and practical foundations of the curriculum, guiding educators in selecting relevant content and learning experiences (Kister, 1999).

3. Focusing on Broad Concepts with Long-Term Value

Broad concepts with long-term value provide learners with enduring understanding. As Hauxwell and Schmidt (1999) note, broad concepts help learners grasp the big picture and see connections among related ideas.

For instance, instead of focusing narrowly on dating, a broader concept such as “relationships” encourages learners to address questions like:

- “What is a responsible citizen?”

- “What constitutes a responsible group member?”

This approach allows learners to dive deeper into the subject matter and develop a clear understanding of core concepts that are transferable across life situations.

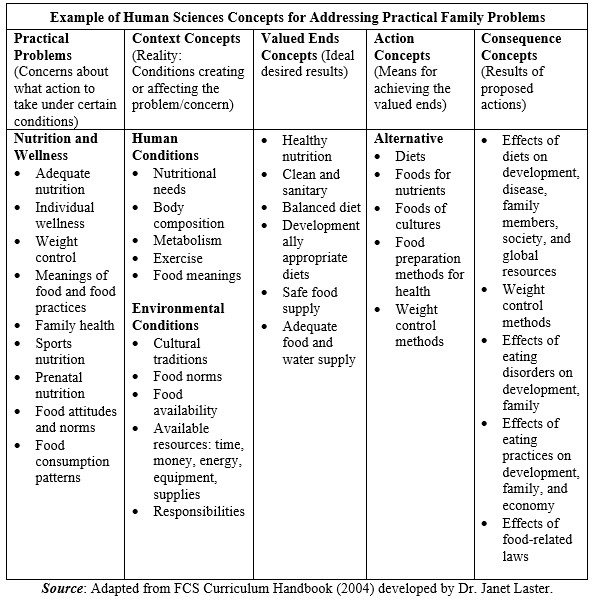

Table 1: Broad Human Sciences Concepts

Integrating Instructional Strategies Consistent with Practical Reasoning

To effectively implement the practical reasoning approach, educators should use instructional strategies that integrate the three systems of action—technical, interpretive/communicative, and reflective (Montgomery, 2008).

- Technical Actions: Hands-on activities, such as labs, focus on procedures and resource management.

- Interpretive/Communicative Actions: Concept-based strategies (e.g., grouping and labeling ideas) or the concept attainment model (e.g., contrasting “yes” and “no” examples) help learners interpret information.

- Reflective Actions: The practical reasoning process guides learners in examining goals, context, consequences, and alternatives to form judgments about “what to do” in a given situation (Olson, 1999).

Practical Reasoning’s Role in Enhancing Learning

When a curriculum is developed with a practical reasoning perspective, educators are better equipped to apply critical literacy skills to improve human conditions. Learners gain the tools to examine their multiple roles in life—such as family members, workers, and citizens—and to address their family, career, and community concerns (Montgomery, 2008).

A practical reasoning-based curriculum combines critical literacy with a learner-centered focus, fostering improved quality of life for individuals, families, and communities while supporting the ongoing assessment and refinement of human sciences curricula.

Evaluating the Practical Reasoning-Based Curriculum

Curriculum evaluation is a critical phase of curriculum development. It involves systematically collecting data to assess the quality, effectiveness, and relevance of a human sciences program or course. Through this process, FCS/human sciences faculty determine whether the curriculum is fulfilling its intended purpose and whether learners are achieving the desired outcomes. For a practical reasoning-based curriculum, the evaluation process should facilitate continuous improvement to better meet the needs of learners, families, and society as a whole.

Two Key Components of Curriculum Evaluation

- Evaluation of Learners

This evaluation takes place before, during, and after instruction. It addresses the fundamental question: Have the course objectives been met? By analyzing learner assessment data, FCS/human sciences professionals identify how many learners have achieved the objectives, the level of their performance, and areas where additional support may be needed. - Evaluation of Instructional Materials and Curriculum Effectiveness

This component examines the relevance and effectiveness of instructional materials, teaching methods, and curriculum design. Insights from evaluation data guide decisions on whether to modify curriculum content, instructional methods, or evaluation strategies. Timely decisions ensure that necessary adjustments are made to keep the curriculum relevant and impactful.

Purposes of Evaluation

Evaluation serves multiple purposes:

- For Individual Learner Progress:

- Identify what learners have gained in terms of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and personal growth.

- Ascertain the learner’s current standing within the class.

- Pinpoint areas where learners need support and the type of assistance required.

- Use data to inform strategies that support each learner’s overall development.

- For Classroom Practices:

- Determine which course objectives have been met.

- Assess the relevance and practicality of methods and activities.

- Identify the need for re-teaching or alternative strategies.

- For Curriculum Materials:

- Evaluate the relevance, usability, appropriateness, and affordability of materials.

- For Community Involvement:

- Assess community attitudes toward and engagement with the curriculum.

By identifying strengths and weaknesses early, evaluation helps save time and resources while increasing the likelihood of a program’s or course’s success.

Types of Curriculum Evaluation

- Pre-Assessment Evaluation

Pre-assessment determines whether learners possess the prerequisite knowledge and skills necessary for new material. This evaluation is particularly helpful at the start of a course, a new school year, or for educators new to a class. - Formative Evaluation

Conducted during the curriculum’s implementation, formative evaluation guides the program’s or course’s development by identifying areas for improvement. It should occur at all stages of curriculum design and delivery. - Summative Evaluation

Summative evaluation occurs at the conclusion of a program or course. It supports major decisions, such as whether to expand, modify, or discontinue the program based on its success or failure. - Impact Evaluation

Impact evaluation assesses how an intervention has influenced outcomes, including both intended and unintended effects. Typically part of summative evaluation, it requires rigorous analysis to compare actual outcomes with what might have occurred without the intervention. These evaluations are often conducted at the district or postsecondary program level and may be reported at state or national levels.

Criteria for Curriculum Evaluation

Key criteria for evaluating a curriculum include:

- Alignment with Standards: The curriculum should align with established academic and professional standards.

- Consistency with Objectives: The curriculum should address its stated objectives effectively.

- Comprehensiveness: The curriculum should encompass a broad range of knowledge and skills relevant to the discipline.

- Relevance and Continuity: The curriculum should address the needs of learners and remain current with societal and professional demands.

Challenges may arise in assessing objectives, especially in certain domains:

- Affective Domain: Measuring traits such as integrity and honesty can be subjective and difficult to assess through traditional methods.

- Psychomotor Domain: Tasks requiring physical coordination (e.g., cooking techniques) often present logistical challenges in assessment.

- Cognitive Domain: While easier to assess, cognitive skills often represent only a fraction of the learning outcomes tested.

Efforts to ensure quality evaluations—such as thorough exam development and rigorous review processes—help address these challenges, particularly at the summative evaluation stage.

Evaluating a Practical Reasoning-Based Curriculum

Evaluating a practical reasoning-based curriculum requires specific considerations to assess its integration of critical reasoning perspectives. Questions to guide this evaluation include:

- To what extent are higher-order thinking skills (e.g., analysis, synthesis, evaluation, creation) promoted?

- What kinds of experiences enable learners to exercise critique?

- How are learners held accountable during classroom dialogue?

- Do learners have opportunities to refine their work?

- How often are learners engaged in collaborative problem-solving?

- Are learners involved in real and relevant problem-solving activities?

- To what extent are learners engaged with their school and broader community?

- Are there opportunities for learners to present their findings?

Comprehensive Curriculum Evaluation

To evaluate the comprehensiveness of a curriculum, consider the following:

- Instructional Methods and Materials: Are these effective and satisfactory, or do they require improvement?

- Individual Learner Needs: Can the evaluation process identify learner needs and guide better planning for their development?

- Feedback for Educators: Does the evaluation provide actionable insights for educators to improve their performance?

Curriculum evaluation is essential for ensuring the quality and effectiveness of FCS/human sciences programs. By systematically analyzing learner progress, instructional materials, and overall curriculum design, educators can refine their approaches and better meet the needs of learners, families, and communities. A well-executed evaluation process not only identifies areas for improvement but also supports the long-term success of educational programs, ensuring their relevance and impact in a rapidly changing world.

Application of Knowledge

Purpose: The purpose of implementing a practical reasoning-based curriculum is that it allows educators to answer these questions, “What knowledge is of most worth?” “Why?” and “What ought to be?” and thereby determine the relevance and value of this course/program in today’s society. Additionally, a practical reasoning-based curriculum involves research that reviews recent issues and trends in the discipline both within the state and across the country. This research allows human sciences professionals to identify key issues and trends that will support the development of rigorous learning standards and competencies.

Task:

- Explain what individuals you would put on your curriculum advisory committee mentioned in this chapter and why.

- Choose a course/program curriculum to implement the practical reasoning perspective. Then develop a gap analysis chart similar to the one described in Chapter 2 to show “what is taught” and “what should be taught” in this curriculum.

- Next, develop a rationale statement that addresses questions such as:

- What is the perennial or emerging problem that needs to be addressed in the curriculum?

- What are the consequences of addressing or not addressing this problem in the curriculum?

- Based on this problem, what is the concept(s) which are the focus of this course or program? and

- Why is it important for learners to understand these concepts?

- Then develop a “broad concepts” table similar to the example provided in this chapter related to the course/program curriculum.

- Lastly, take a look at the instructional strategies provided in this course/program curriculum and enhance one of them with the practical reasoning approach that also integrates one or more of the core academic areas (e.g., English, math, science, history, etc.) and all three systems of action. Provide an example of this instructional strategy.

References

Baldwin, E. (1999). Chapter 3: FCS curriculum: What ought to be? In J. Johnson & C. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: Toward a critical science approach. Teacher Education Yearbook 19, 32-44. American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences.

Brown, M. (1980). What is home economics education? University of Minnesota.

Brown, M., & Paolucci, B. (1979). Home economics: A definition. American Home Economics Association.

Gordon, W. R., Taylor, R. T., & Oliva, P. F. (2019). Developing the curriculum: Improved outcomes through systems approach (9th ed.). Pearson.

Hauxwell, L., & Schmidt, B. L. (1999). Developing curriculum using broad concepts. In J. Johnson & C. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: Toward a critical science approach. Teacher Education Yearbook 19, 91-102. American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences.

Kister, J. (1999). Chapter 4: Forming a rationale: Considering beliefs, meanings, and context. In J. Johnson & C. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: Toward a critical science approach. Teacher Education Yearbook 19, 45-57. American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences.

Laster, J. (2004). Chapter 6: Principles of teaching practice in family and consumer sciences education. Curriculum Handbook published by the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

LEADFCS Education. (2018). National standards for family and consumer sciences. http://www.leadfcsed.org/national-standards.html

LEADFCS Education. (2008). National standards for family and consumer sciences reasoning for actional standards and process questions. http://www.leadfcsed.org/uploads/1/8/3/9/18396981/process_framework_overview.pdf

Montgomery, B. (2008). Curriculum development: A critical science perspective. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 26(National Teacher Standards 3), 1-16. http://www.natefacs.org/Pages/v26Standards3/v26Standards3Montgomery.pdf

National Association of State Directors of Career Technical Education Consortium (NASDCTEc). (2013). The state of career technical education: An analysis of state CTE standards. Retrieved from https://careertech.org/sites/default/files/State-CTE-Standards-ReportFINAL.pdf

National Association of Teacher Educators for Family and Consumer Sciences (NATEFACS). (2020). Teacher education competencies. https://www.natefacs.org/Docs/2020/FCS%20TeacherEducationStandards-Competencies%20NATEFACS-2020.pdf

National Association of Teacher Educators for Family and Consumer Sciences (NATEFACS). (2018). Teacher education standards. https://www.natefacs.org/Docs/2020/FCS%20TeacherEducationStandards-Competencies%20NATEFACS-2020.pdf

Nickols, S. Y., Ralston, P. A., Anderson, C., Browne, L., Schroeder, G., Thomas, S., & Wild, P. (2009). The Family and Consumer Sciences Body of Knowledge and the cultural kaleidoscope: Research opportunities and challenges. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 37(3), 266-283.

Olson, K. (1999). Practical reasoning. In J. Johnson & C. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: Toward a critical science approach. Teacher Education Yearbook 19, 132-142. American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences.

Plihal, J., Laird, M., & Rehm, M. (1999). Chapter 1: The meaning of curriculum: Alternative perspectives. In J. Johnson & C. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: Toward a critical science approach. Teacher Education Yearbook 19, 2-22. American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences.

Wiles, J. W., & Bondi, J. C. (2019). Curriculum development: A guide to practice. (9th ed.). Pearson.