4 Teaching and Learning Processes: Content

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to:

- Explain the mission and philosophical foundations of Family and Consumer Sciences (FCS), emphasizing its focus on addressing practical and enduring challenges impacting individuals, families, and communities.

- Analyze the conceptual meaning of key phrases in the FCS mission statement and their implications for empowering families as transformative agents of societal change.

- Evaluate the principles of mission-driven FCS programming, including learner-centered approaches, problem-based curriculum design, and authentic instruction and assessment.

- Apply the Systems of Action Framework (technical, communicative, and reflective knowledge) to develop interdisciplinary FCS curricula that address complex, real-world problems.

- Integrate critical thinking, practical reasoning, and social processes (communication, leadership, and management) into FCS teaching and learning environments to foster ethical decision-making and problem-solving skills.

- Design FCS teaching and learning experiences that align with the Reasoning for Action Standards and the FCS National Standards to develop knowledge, skills, and competencies addressing personal, family, and community challenges.

- Critically reflect on the educator’s role in fostering democratic, inclusive, and socially responsible learning environments guided by the practical reasoning perspective.

Family and Consumer Sciences (FCS) is a service-oriented profession with a mission that addresses practical and enduring (perennial) challenges impacting individuals and families (Brown, 1980). The mission statement, introduced in Chapter 1, serves as the philosophical foundation, articulating the core values of the FCS profession when working to accomplish its aim to improve the human condition (Kieren et al., 1984).

This mission is grounded in the belief that families, as social institutions, are agents of transformation (Brown & Paolucci, 1979). In their individual roles, and in collaboration with others, families have the power to bring about societal change (Brown & Paolucci, 1979). As transformative agents, families’ work is both purposeful and action-oriented, aiming to: 1) develop individual potential, 2) meet family needs, and 3) contribute to community goals (Wright, 1999, p. 106).

Mission Driven: Teaching & Learning

Teaching and learning can be understood as “the transformation process of knowledge from teachers to students” (Munna & Kalam, 2021, p. 1). Teaching involves educators making decisions when designing objectives, selecting resources, and using strategies to foster knowledge, skills, and understanding (Munna & Kalam, 2021). Learning reflects the learner’s experience. Taken together, this dynamic interaction is multifaceted and complex.

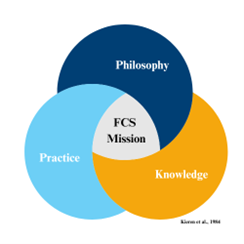

Within FCS environments, the mission statement defines and unifies the work of the profession by framing an educator’s work as a system of three interconnected elements: philosophy, knowledge, and practice (Kieren et al., 1984).

Mission Oriented Profession

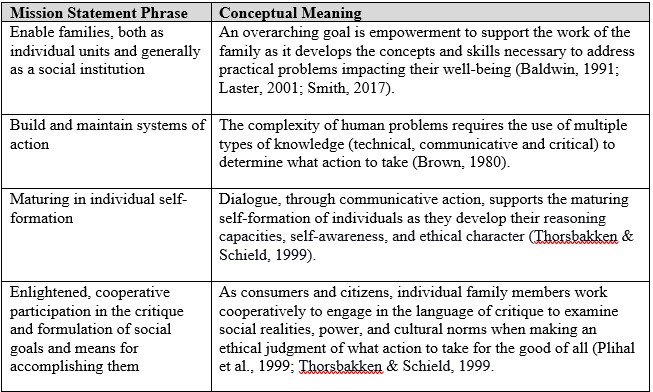

Examining the meaning of each phrase within the mission statement provides the FCS profession with a conceptual understanding of its role as a service profession, which allows it to focus its practice and knowledge on “persistent and recurring human problems that impact families within the context of their communities” (Laster, 2001, p. 63).

When the conceptual meaning of the mission statement is analyzed within the context of teaching and learning processes, several core principles emerge that define and unify how FCS professionals approach their work through a critical science orientation. As a mission-driven profession, Laster (2001, pp. 63-68) identified the following key principles of FCS programming:

- In partnership with families: The learning process and its outcomes support and complement the role of families.

- Practical, problem-based: The curriculum centers around recurring, real-world challenges that families and communities face, with an emphasis on developing learners’ knowledge and skills for ethical action.

- Learner-centered: Learners are actively involved in the process, collaborating with educators to co-create both the content and learning experience.

- Authentic instruction and assessment: Learning environments provide hands-on, real-world experiences and assessment focuses on developing practical knowledge and skills.

- Conducted in caring, challenging, and democratic environments: Educators serve as leaders and co-investigators, fostering pro-social, collaborative learning spaces.

- Process-oriented to develop reasoning and action-thinking skills: Practical reasoning is central in FCS, fostering both intellectual and social skills necessary for ethical decision-making when addressing problems.

- Facilitated through open-ended, critical questioning: Questioning is the primary method in teaching and learning, promoting deeper critical thinking.

- Integrated learning: FCS embraces multidisciplinary learning, incorporating various disciplines and concepts to explore the complexity of practical problems. Learning environments also emphasize the connection between the content and career opportunities, including work-based learning and career exploration.

- Reflective practice: Educators engage in continuous reflective (examining what is happening) and reflexive thinking (considering the impact on others) to continually refine their curriculum and teaching practices.

Educator Philosophy: Purpose of FCS

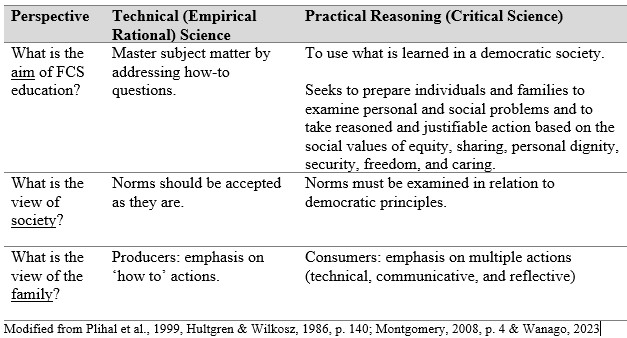

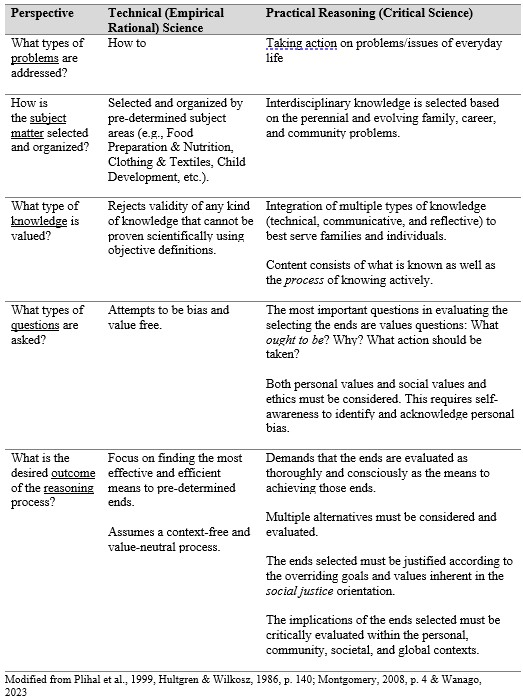

To achieve mission-driven teaching and learning principles, educators must critically evaluate their paradigm. A paradigm represents the thought patterns—values, beliefs, and assumptions—that individuals use to make sense of and find purpose in their work (McGregor, 2019). Historically, the FCS profession has been grounded in an empirical-technical science approach, focusing on “what” and “how” questions and developing skills to “manage” things to meet basic needs (Baldwin, 1991, p. 44). While important, this approach does not adequately address the complexities of challenges impacting today’s families.

Brown and Paolucci (1979) called for a transformative shift in the profession’s paradigm, advocating for a practical reasoning (critical science) perspective that adds the normative question of what “should or ought to be done” (McGregor, 2019). This perspective sees families not just as consumers of technical knowledge but also as users of communicative and reflective knowledge to navigate today’s multifaceted challenges. As agents of transformation, the practical reasoning approach highlights the need to empower individuals and families as they make moral and ethical judgments for the greater good (Plihal et al., 1999).

FCS Content

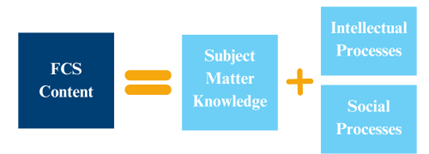

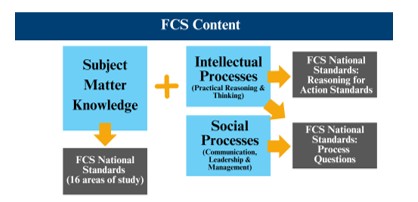

Practical problems (introduced in Chapter 2) inform what content to prioritize in FCS educational experiences. The term ‘practical’ means thinking before acting by evaluating the reasons for different actions and their consequences (McGregor, 2019). To effectively address practical problems, the content encompasses both the subject matter knowledge and the development of intellectual and social processes (Laster, 2001). These processes are the skills and dispositions that learners use to construct meaning from the content and apply it to their lives (Costa & Liebmann, 1997). By integrating both types of content, teaching and learning experiences become transferable, equipping learners to address both present and future concerns.

FCS Content

Subject Matter Knowledge

Selecting which practical problems to focus on in FCS instruction should be a collaborative decision between educators and learners. Conducting a gap analysis allows them to compare “what is” with “what ought to be” by combining research-driven information with personal experience (Johnson & Montgomery, 1997). The gap analysis, as described in Chapter 2, offers insights into the content knowledge and skills that need to be developed. It also captures perceptions of the problem at the individual, family, and community levels and highlights areas of oppression, habits, or power structures that need to change to fully address the issue (Montgomery, 2008).

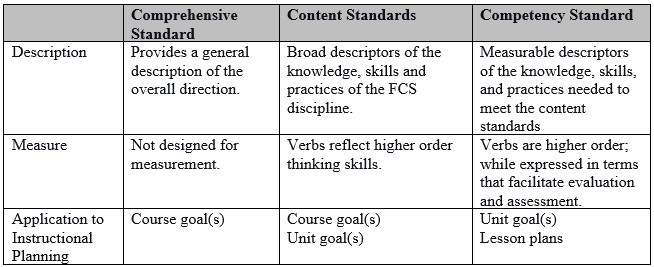

In determining which practical problems should shape the subject matter within FCS education, the Family and Consumer Sciences Body of Knowledge and National Standards define the content that should be incorporated into teaching and learning experiences. The FCS National Standards are organized into sixteen areas of study under the broader FCS umbrella. Given the multidisciplinary nature of FCS, addressing complex problems may require the integration of several areas of study into a single course. Each area of study includes three critical elements (LEADFCS, 2008).

For example, an educator may be teaching a Food and Nutrition course. After completing a gap analysis, the instructor has defined a practical problem: “What should be done to utilize resources, knowledge, and skills to manage food choices that promote well-being?” When organizing the course to address components of the problem, the educator designed a unit titled “What is healthy?”

- Comprehensive Standard: 14.0: Nutrition and Wellness

- Content Standard: 14.2: Examine the nutritional needs of individuals and families in relation to health and wellness across the lifespan.

- Competency Standards:

- o 2.1: Evaluate the effect of nutrition on health, wellness and performance.

- o 2.4: Analyze the sources of food and nutrition information including food labels, related to health and wellness.

Valuing Multiple Types of Knowledge: Systems of Action

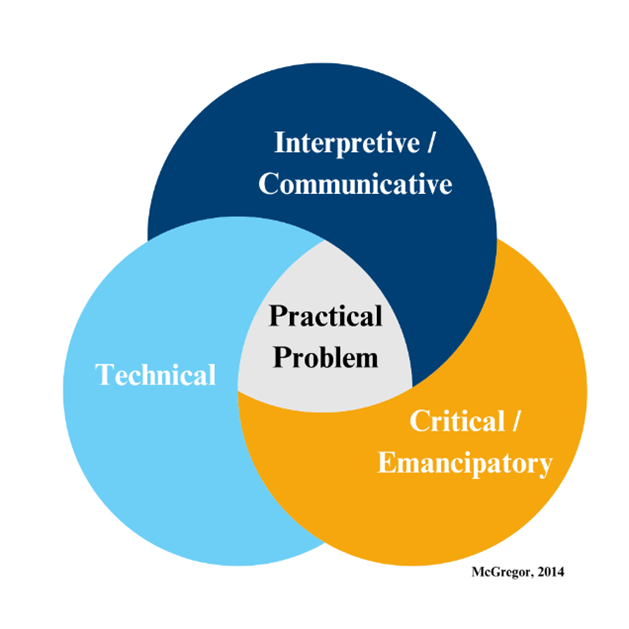

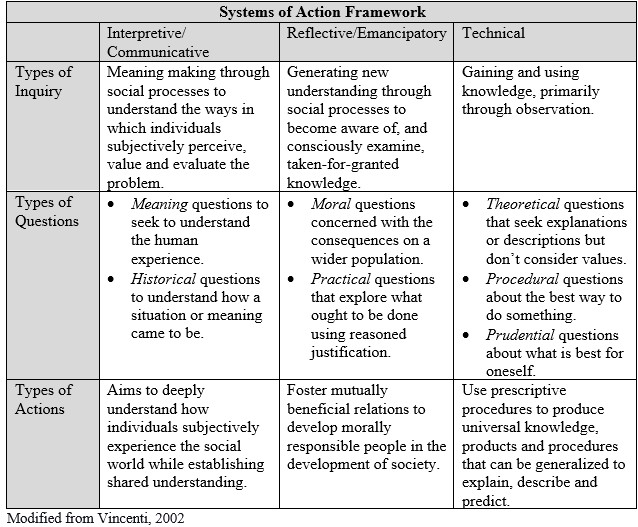

To reflect the complexity of human problems, Brown and Paolucci developed the Systems of Action Framework. The framework includes three types of inquiry—technical, communicative, and reflective—each one valuing a different form of knowledge, posing different types of questions, and leading to distinct actions. The knowledge generated from each type of inquiry is crucial for making decisions that can be both morally and intellectually justified (Hultgren & Wilkosz, 1986), which is why the framework is referred to as a “system” of actions.

Systems of Action Framework

A key feature of a teaching and learning environment guided by the practical reasoning perspective is that “content develops in response to the questions asked” (Smith, 2004, p. 50). Technical questions are considered alongside communicative and critical questions. When using questions from each type of inquiry to develop the subject matter content, educators facilitate dynamic environments that seek to address the root causes of problems, rather than simply treating the symptoms from a “technical, quick fix” perspective (McGregor, 2003, p. 2).

Intellectual and Social Processes

In an FCS environment, intellectual and social learning processes also contribute to the content necessary for individuals to develop the skills needed to address practical issues affecting family and community life (Laster & Johnson, 2001). Processes differ from skills; while a process provides the framework for systematic action to achieve a goal or task, skills are the abilities to perform tasks effectively by integrating knowledge, experience, and practice (Winch, 2010).

Intellectual Processes

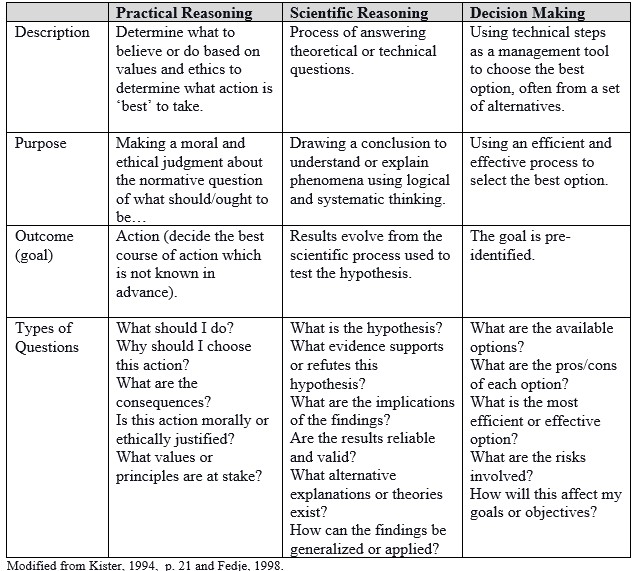

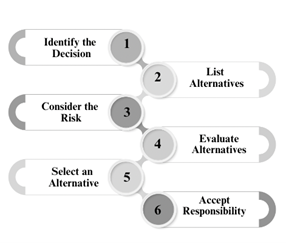

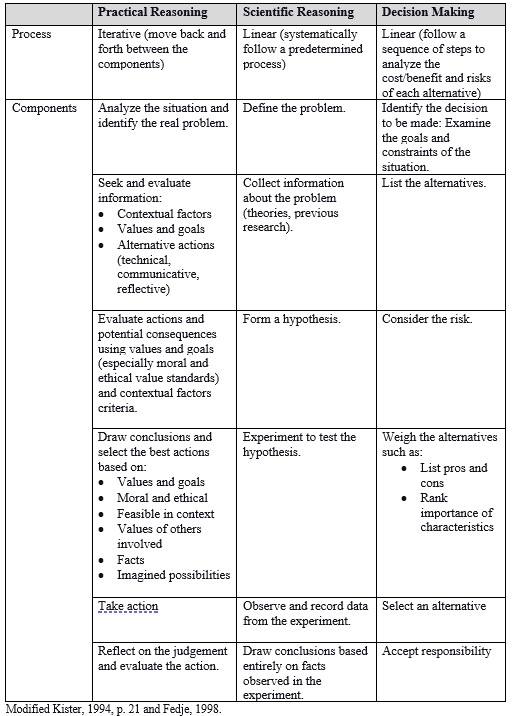

The intellectual (thinking) processes within FCS environments focus on developing reasoning skills, which are crucial for moral-ethical decision-making. Reasoning itself is a process. As individuals develop their reasoning skills, they become more adept at critically analyzing information and considering various perspectives that influence decisions about which actions to take. Several thinking processes—practical reasoning, scientific reasoning, and decision-making—are essential for individuals to successfully fulfill their work and family roles (Fedje, 1998).

Although these intellectual processes are closely related, each has a distinct purpose to address different types of questions based on the problem’s context and type. For example, scientific problems involve technical questions that generate factual knowledge. Decision making is a linear process where the goal is pre-defined, and the emphasis is on using an efficient process to select the best option. Whereas value problems that require individuals and families to make a moral judgment about what “should/ought to be done” require practical reasoning as the goal is not pre-defined (Kister, 1994).

The components of each thinking process also differ due to the various types of questions and purposes. When individuals engage in scientific reasoning or decision-making, the process is linear and follows a systematic sequence. In contrast, practical reasoning (described in Chapter 3) is iterative, allowing individuals to move back and forth between components as their knowledge evolves.

Practical Reasoning Decision Making

Teaching and learning processes in an FCS environment emphasize practical reasoning as the central thinking process, given that perennial problems affecting individuals and families often determine the content priorities (Laster & Johnson, 2001). Nevertheless, all three intellectual processes—practical reasoning, scientific reasoning, and decision-making—are integral to FCS environments. Practical reasoning requires the use of scientific reasoning to identify and assess the information necessary to address a problem. Practical reasoning also requires the use of decision-making to evaluate the consequences of different choices and create a plan of action.

Thinking Skills as Components of Reasoning

Intellectual processes require the use of critical and creative thinking skills within the reasoning process (Fedje, 1998):

- Critical thinking skills: Critical thinking differs from practical reasoning. While practical reasoning focuses on deciding the best course of action within a problem’s context, critical thinking involves developing a critical consciousness. This helps individuals assess whether the information used to define the problem and evaluate alternatives is reliable, relevant, and adequate (Kister, 1994). A fundamental aspect of critical thinking is perspective-taking (Southworth, 2022), which allows individuals to confront cognitive biases by recognizing that others may have different values and beliefs. These different perspectives must be taken into account when making decisions that will affect all involved, considering both short- and long-term consequences from multiple viewpoints.

- Creative thinking skills: Creative thinking enables individuals to think divergently, exploring various alternatives that may help address a problem.

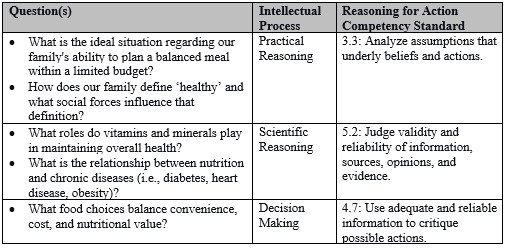

Reasoning for Action Standards

Recognizing the significance of FCS content as both subject matter knowledge and process, the FCS National Standards also include the Reasoning for Action Standards. These comprehensive standards emphasize that learners will “use reasoning processes individually and collectively to take responsible action for families, workplaces, and communities” (Fox, 2008, p. 2). The Reasoning for Action Standards are organized with five content standards and subsequent competency standards. When designing teaching and learning experiences, educators should identify what Reasoning for Action Standards reflect the process of learning. For example, as an educator continues to plan his/her unit “What is healthy?”, he/she may identify the following questions that result in different types of intellectual processes.

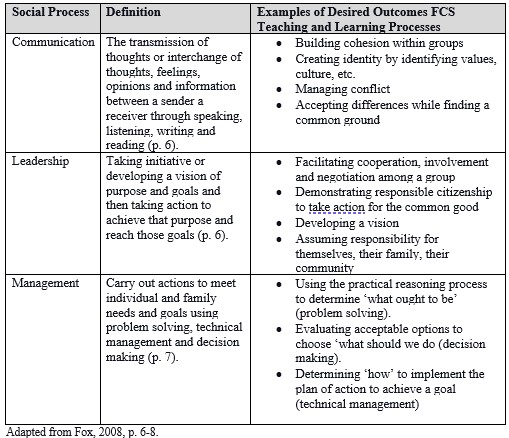

Social Processes

When examining practical problems that affect families, the reasoning process involves using action-oriented questions to analyze issues within the context of the problem setting, considering multiple perspectives to take socially responsible action for the benefit of both oneself and others (Laster & Johnson, 2001). Therefore, an individual’s ability to engage in social processes becomes a crucial component of FCS content. Social processes refer to the patterns of interaction and relationships that shape the behaviors, attitudes, and values of individuals and groups (Loomis, 1943). The Family and Consumer Sciences National Process Standards identify three key social processes—communication, leadership, and management—that learners develop as part of the teaching and learning experience (Fox, 2008).

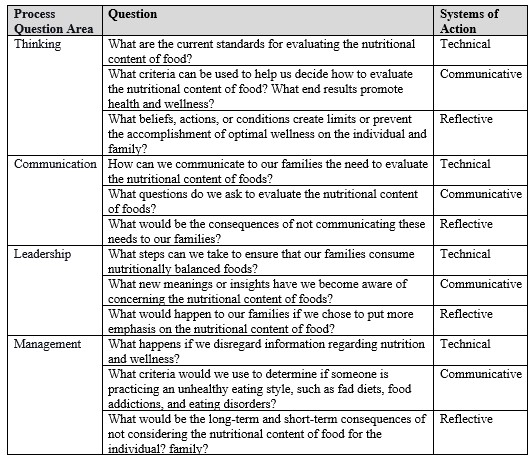

To guide educators in cultivating dynamic environments that foster thinking, communication, management, and leadership processes, the National FCS Standards provides a Process Questions Framework with questions for each National FCS Content Standard. Each process area contains three guiding questions, organized according to the Systems of Action Framework (technical, communicative, and reflective). When designing teaching and learning experiences, these questions should be integrated into instructional activities to support the combination of multiple types of knowledge as learners develop their abilities in each process area.

For example, the Healthy Eating Unit described in this chapter is guided by National FCS Content Standard 14.2: Examine the nutritional needs of individuals and families in relation to health and wellness across the lifespan. As an educator is developing their learning experiences they can use this list of questions.

Educator Philosophy: Selecting Content

When educators adopt a Practical Reasoning Perspective, they make intentional decisions to develop both subject matter knowledge and the intellectual and social processes needed to address personal, family, and career challenges, both in the present and the future. In this approach, the teaching and learning environment balances the development of technical, how-to skills with communicative and reflective knowledge. These are organized around practical problems, acknowledging their complexity while equipping learners with process skills that are transferable across various aspects of life. In examining these problems, practical reasoning becomes the central thinking process, as it addresses the normative question, “What ought to be?” This encourages learners to consciously analyze the consequences of their choices, considering their impact not only on themselves but also on their families, communities, and the wider world, before making decisions about the appropriate course of action.

FCS Content + Standards

The content that comprises FCS teaching and learning experiences includes subject matter knowledge and intellectual and social processes. The content is informed by the practical problem and connected to the FCS profession by aligning to the National Standards.

References

Brown, M. M., & Paolucci, B. (1979). Home economics: A definition. American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences.

Brown, M. M. (1980). What is home economics education? University of Minnesota, Minnesota Research and Development Center for Vocational Education.

Baldwin, E. E. (1991). The home economics movement: A “new” integrative paradigm. Journal of Home Economics, 83(4), 42-48.

Costa, A. L., & Liebmann, R. M. (2001). Envisioning process as content: Toward a renaissance curriculum. Corwin Press, Inc.

Fedje, C.G. (1998). Helping learners develop their practical reasoning abilities. In R. Thomas & J. Laster (Eds.), Inquiry into Thinking- Yearbook 18 (pp. 29-46). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Fox, W. (2008). National standards for family and consumer sciences reasoning for action standards and process questions. National Association of State Administrators of Family and Consumer Sciences. https://www.leadfcsed.org/uploads/1/8/3/9/18396981/process_framework_overview.pdf

Hultgren, F., & Wilkosz, J. (1986). Human goals and critical realities: A practical problem framework for developing home economics curriculum. Journal of Vocational Home Economics Education, 4(2),135-154.

Johnson, J., & Montgomery, B. (1997). Advanced instructional theory resource packet. Lincoln: University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Kieren, D., Vaines, E., & Badir, D. (1984). The home economist as a helping professional. Ronald P. Frye & Company.

Kister, J. (1994). Life planning resources guide. A resource for teaching the life planning course area of Ohio’s work and family life program. Ohio State University. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED375287

LEADFCS Education. (2008). National standards for family and consumer sciences reasoning for actional standards and process questions. http://www.leadfcsed.org/uploads/1/8/3/9/18396981/process_framework_overview.pdf

Loomis, C. P. (1943). Social processes: An introduction to sociology. American Journal of Sociology, 81(5), 1143-1173. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2777091

Laster, J. F., & Johnson, J. (2001). Major trends in Family and Consumer Sciences. In S SS. Redick, A. Vail, B. P. Smith, R. G. Thomas, P. Copa, C. Mileham, C. Fedje, & K. Alexander (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences: A chapter of the curriculum handbook. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

Laster, J. (2001). Chapter 7: Principles of teaching practice in family and consumer sciences education (pp. 63-87). Curriculum Handbook published by the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2003). Critical science approach – A primer. Kappa Omicron Nu FORUM, 15(1). https://publications.kon.org/archives/forum/forum15-1.html

McGregor, S. (2019). Paradigms and normativity: What should FCS do in light of 21st century change? Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 111(3), 10-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.14307/JFCS111.3.10

Montgomery, B. (1999). Continuing concerns of individuals and families. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 80-90). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Montgomery, B. (2008). Curriculum development: A critical science perspective. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 26(National Teacher Standards 3), 1-16.

Munna, A. S., & Kalam, M. A. (2021). Teaching and learning process to enhance teaching effectiveness: A literature review. International Journal of Humanities and Innovation, 4(1), 1-4.

Plihal, J., Laird, M., & Rehm, M. (1999). The meaning of curriculum: Alternative perspectives. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 2-22). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Slavin, R. E. (1995). Cooperative Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice (2nd ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

Smith, B. P. (2004). FCS curriculum development and the critical science perspective. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 96(1), 49-51.

Smith, B. P. (2010). Instructional strategies in family and consumer sciences: Implementing the contextual teaching and learning pedagogical model. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences Education, 28 (1), 23-38.

Smith, M. G. (2017). Pedagogy for home economics education: Braiding together three perspectives. International Journal of Home Economics, 10(2), 7-16.

Southworth, J. (2022). Bridging critical thinking and transformative learning: The role of perspective taking. Theory and Research in Education, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/14778785221090853

Thorsbakken, P., & Schield, B. (1999). Family systems of action. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 117-131). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Wanago, N. C., (2023). A Qualitative Exploration of the Home Economics/Family and Consumer Sciences Professions Critical Science Paradigm Shift [Doctoral dissertation, Texas Tech University]. Texas Tech Repository. https://ttu-ir.tdl.org/items/65ad1ae5-13a2-472c-9db8-cced204a8859

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Winch, C. (2010). The relationship between practical reasoning and competence in vocational education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 42(5-6), 540-551. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2008.00488.x

Wright, P.L., (1999). Work of the family. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 103-116). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Vincenti, V. B. (2002). Addressing problems effectively using critical science. American Home Economics Association.