1 History and Philosophy of Practical Reasoning (Critical Science) in Family and Consumer Sciences/Human Sciences

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to:

- Recognize the evolution of practical reasoning within the Family and Consumer Sciences (FCS) discipline, including key historical contributions and the transition from Home Economics to a modern interdisciplinary approach.

- Analyze the contributions of Ellen Swallow Richards to the practical reasoning perspective, highlighting how her work in chemistry and domestic science addressed societal problems and set a foundation for modern FCS practices.

- Differentiate the empirical-rational science (technical) approach from practical reasoning in FCS, understanding the characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each method in addressing everyday problems.

- Explore the principles of the practical reasoning (critical science) approach, focusing on its application to complex, ethically significant problems and its role in empowering individuals and communities to enact positive change.

- Connect the practical reasoning perspective to the Family and Consumer Sciences Body of Knowledge (FCS-BOK), examining how this theoretical framework supports addressing perennial and emerging problems within the discipline.

- Apply the practical reasoning perspective and the FCS-BOK to real-world problems, developing comprehensive strategies that address the underlying causes and promote sustainable solutions for individuals, families, and communities.

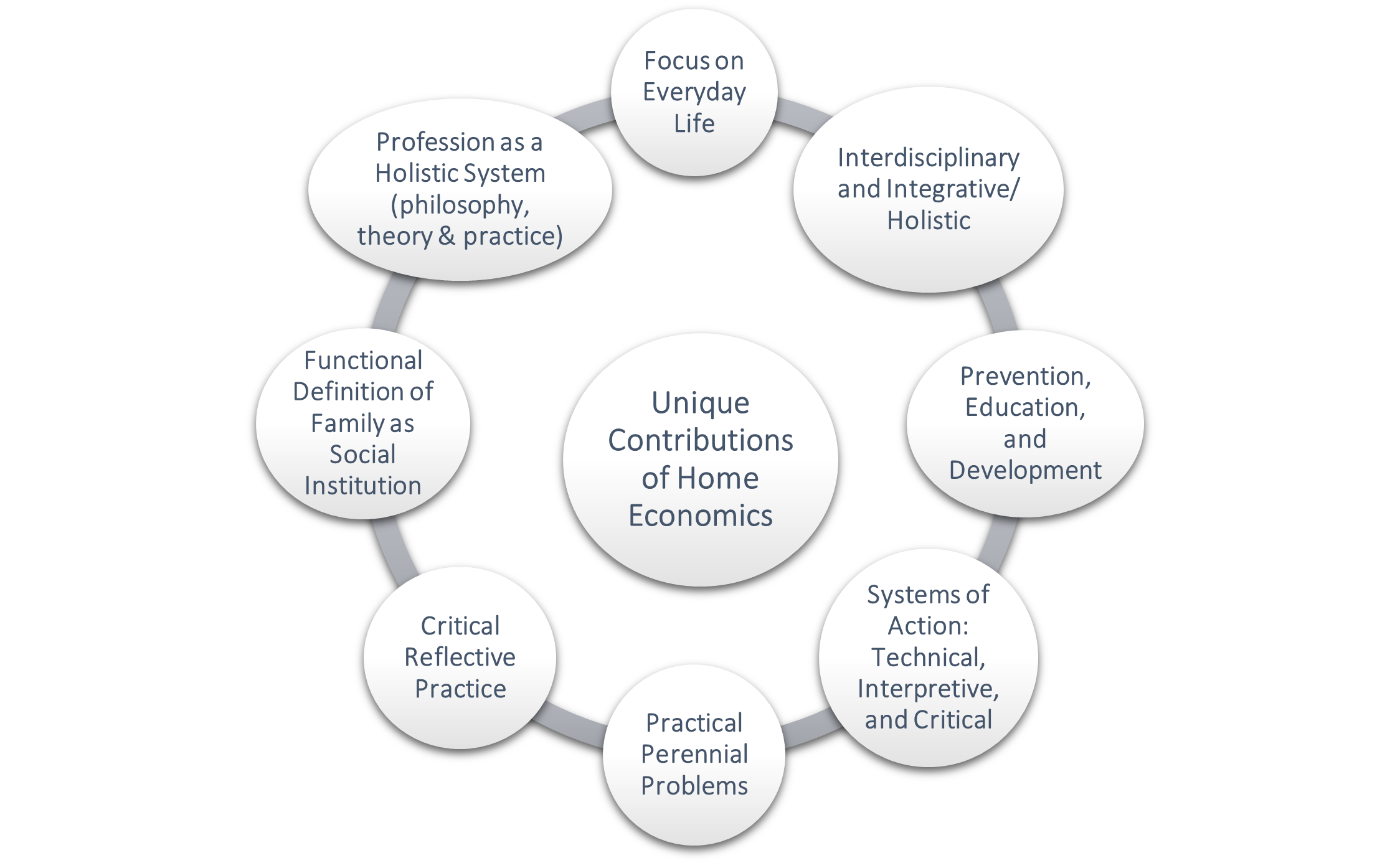

Human Sciences is a field of study that expands our understanding of the human world through a broad interdisciplinary approach. Family and Consumer Sciences (FCS), formerly known as Home Economics, is a discipline area within Human Sciences that empowers individuals and families throughout life to manage the challenges of living and working in a complex and diverse global society (AAFCS, 2023, para. 1). With this in mind, two FCS practitioners, Drs. Marjorie Brown and Beatrice Paolucci were instrumental in developing the perspective of practical reasoning (critical science) as a tool to help foster changes to improve the condition of individuals and families they served (McGregor, 2014). In other words, the practical reasoning perspective encouraged FCS professionals “to move from a focus on adapting to the status quo (what is) to a focus on developing a rationally and ethically justifiable ideal state (what ought to be)” (Vincenti & Smith, 2004, p. 67).

Marjorie Brown: Advocating for Critical Thinking and Change

Marjorie Brown was a visionary educator and advocate within the field of Home Economics. Her academic and professional work was marked by a strong commitment to integrating social justice issues with the practical aspects of home economics (McGregor, 2014; Brown, 1980). Brown’s work emphasized the importance of education in empowering individuals, particularly women, to critically examine and address the societal structures affecting family life (McGregor, 2014; Brown, 1980).

Key Contributions:

- Redefinition of Home Economics: Brown played a crucial role in redefining the field, moving it beyond its traditional focus on domestic skills to include critical social issues affecting families and communities (McGregor, 2014; Brown, 1980).

- Critical Pedagogy: Brown introduced and emphasized the importance of critical thinking and reflective inquiry in home economics pedagogy, encouraging learners to analyze and question societal norms and envision transformative changes (McGregor, 2014; Brown 1980).

- Empowerment through Education: Brown advocated for a curriculum that prepared learners to understand and challenge societal issues, empowering them to effect change (McGregor, 2014; Brown, 1980).

- Legacy and Impact: Her work has inspired educators to include critical thinking, social justice, and advocacy in their teaching, emphasizing individuals and families as agents of change (McGregor, 2014; Brown, 1980).

Beatrice Paolucci: Shaping Family Policy through Practical Reasoning

Beatrice Paolucci was a scholar who took a multidisciplinary approach to the study of home economics, incorporating insights from sociology, anthropology, and psychology to understand family dynamics and consumer behavior (Bubolz, 2002).

Key Contributions:

- Holistic Approach to Family Studies: Paolucci viewed families comprehensively, considering cultural, economic, and social factors (Bubolz, 2002).

- Practical Reasoning in Education: She developed the concept of practical reasoning, emphasizing the application of theoretical knowledge to address real-world problems (Bubolz, 2002).

- Ethical Considerations in Policy Development: Paolucci emphasized ethical considerations in developing and implementing family policies, advocating for just and equitable approaches (Bubolz, 2002).

- Legacy and Impact: Her work has provided a framework for analyzing family issues ethically, inspiring educators, policymakers, and practitioners to integrate multidisciplinary perspectives (Bubolz, 2002).

Integrating the Contributions of Brown and Paolucci

Brown and Paolucci’s contributions to FCS offer a powerful framework for understanding and addressing family issues. Brown’s focus on critical pedagogy and social justice, combined with Paolucci’s emphasis on practical reasoning and ethical policy development, provides a comprehensive approach to FCS education (Brown, 1980; Bubolz, 2002). Their legacies continue to inspire efforts to empower families and individuals, promoting equitable and thoughtful engagement with societal challenges.

This chapter will discuss the historical development of the practical reasoning perspective; distinguish the differences between the empirical-rational science (technical) and the practical reasoning (critical science) perspectives in FCS; and examine the connection of the practical reasoning perspective to the FCS Body of Knowledge.

Note: McGregor, S. L. T. (2010). Name changes and future-proofing the profession: Human sciences as a name? International Journal of Home Economics, 3(1), 20-27.

Note: McGregor, S. L. T. (2010). Name changes and future-proofing the profession: Human sciences as a name? International Journal of Home Economics, 3(1), 20-27.

The Practical Reasoning Impact by Ellen Swallow Richards

The practical reasoning perspective “includes knowledge focused on human interests, communicative theory grounded in dialogue, and actions based on moral consciousness when addressing practical perennial problems” (Vincenti & Smith, 2004, p. 1). Ellen Swallow Richards (1842-1911), the founder of Home Economics, is a perfect example of integrating these aspects into all of the issues individuals and families faced during her time even though this perspective was not adopted until 1979. Ellen was a trailblazing leader and educator because she took an interest in the study of chemistry, domestic science, and the overall well-being of people. As the first woman to attend and graduate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), she was very active in the chemistry lab and felt more women should be involved in science (Cornell University, 2001). However, she saw and experienced the struggles women had in being able to pursue science at the college level, as well as other setbacks due to unjust hardships women faced during that time. Nonetheless, MIT opened the first laboratory of sanitary chemistry in the country in 1883, and Ellen was appointed an assistant in chemistry and later, an instructor (American Chemical Society, 2021). During this time, she was instrumental in examining water pollution issues, which ultimately led to the creation of the first modern wastewater treatment facility in Lowell, Massachusetts (American Chemical Society, 2021). This is the first example of a problem she saw that needed to be resolved because of the impact contaminated water and poor sanitation were having on people’s health.

Another example of how Ellen dealt with the problems affecting people during her time was when she turned her home into a living laboratory of study. Ellen set up model kitchens that were open to the public so they could see how to properly manage a kitchen (Science History Institute, 2021). She saw there were bad food issues that increased the number of people becoming vulnerable to diseases and illnesses, as well as hunger. She became interested in not only eliminating “altered” or “bad” food but also bringing food science into the home so that people could understand the science behind the preparation of good, nutritious food at a low cost (Levenstein, 1980). Ellen is also credited with starting the school lunch program in Boston in the late 1800s, which fed over 4,000 children a day (HaywoodWeavers, 2011). Richards said, “I believe it will be held a crime in the twentieth century to lure young bodies and minds to college [school] under the pretense of education only to poison them slowly with bad . . . food” (Clarke, 1973, p. 137). When moving forward in this book, is important to remember the societal problems Ellen took on and reflect on the practical reasoning nature of her work. More information on the societal issues Ellen tackled can be found here.

Source: The Rumford Kitchen Building [Photograph] from Report of the Massachusetts Board of World’s Fair Managers, 1894.

What is the Empirical-Rational Science (Technical) Approach?

The empirical-rational science (technical) approach aims to produce technically useful knowledge, products, and procedures that explain, describe, and predict how the world, including how humans work and/or behave (Vincenti & Smith, 2004). Traditionally in the FCS profession, this has been the most used approach for decades because it provides the same information to every individual assuming it would be helpful to all and does not require complex thinking, but instead a “quick fix” perspective (McGregor, 2003). Montgomery (1999) stated there were two types of problems we encounter in our lives: “how to” problems and “what should be done” problems. “How-to” problems are associated with the technical approach because a specific goal or product is identified, and specific steps are used to complete it (Montgomery, 1999). Examples of “how-to” problems include: how to develop a household budget, how to plan a meal, how to fill out a job application, and how to conserve energy, among others. Freire (1986) called this a “banking approach” to professional practice because it rendered individuals as empty vessels as opposed to empowering them to be critical thinkers and problem solvers.

Source: From Around the World in Academia by S. Dudani, 2020, WordPress. Used with permission.

“How-to” problems have been classified into subject matter areas such as apparel and textiles, nutrition and foods, interior design, interpersonal relationships, and child development, to name a few. For example, the problem of how to assemble a clothing item can be solved by learning sewing techniques and following the steps of a clothing pattern. When the problem is encountered repeatedly, people develop a habit in which to solve the problem in one preferred way (Montgomery, 1999). Therefore, an advantage of using the technical approach is that when techniques, instructions, rules, or steps are learned, they can be applied every time a “how-to” problem occurs (Montgomery, 1999). A concern in focusing on “how-to” problems in the technical approach is that not all problems can be best, or ethically solved, by “how-to” solutions. However, “how-to” problems within the technical approach can work in tandem with the practical reasoning approach if these problems are part of a larger concern and additional context and cultural factors are considered (Montgomery, 1999).

What is the Practical Reasoning (Critical Science) Approach?

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Drs. Marjorie Brown and Beatrice Paolucci, drawing upon many national and international scholars, introduced practical reasoning (critical science) as a philosophical foundation for the FCS profession. The central focus of the practical reasoning approach is for individuals, families, and communities to think about the problems or issues of everyday life and to take action toward the improvement of these problems (McGregor, 2003). In addition, it addresses complex problems that have ethical consequences and empowers people to assume agency for their own lives, families, communities, states, and countries. The main goal of the practical reasoning approach is to improve individuals’ and families’ lives by helping them see there are ways to change the discrepancies that exist between the ideal (desirable) and the reality of life situations (McGregor, 2003). If individuals and families are taught how to improve their condition, they are more likely to work together to achieve this improvement. This, in turn, reduces the number of individuals and families marginalized, oppressed, excluded, or judged, and instead helps them feel empowered to drive their thought process (McGregor, 2003).

Similarly to the technical approach, the practical reasoning approach is associated with “what should be done” problems, also known as perennial problems or continuing concerns. This type of problem “focuses on the broader underlying questions, issues, or concerns of individuals and families” (Montgomery, 1999, p. 82). Brown and Paolucci (1979) believed the focus of the FCS profession should be to examine and take action on “what should be done” problems. “What should be done” problems are normally stated as important questions that need to be addressed, such as “What should be done to reduce food insecurity?”, “What should be done to help families achieve affordable housing?,” or “What should be done to decrease the rate of child abuse in our community?” “What should be done” problems do not come with a predetermined solution like “how-to” problems because social changes are ongoing and these perennial problems need to be continuously reexamined for revised or new solutions (Montgomery,1999). “What should be done” problems have been characterized as a process an artist uses to develop and complete a sculpture: the end goal or value-end of the sculpture, the contextual factors that influence the process used in developing the sculpture, and the rational planning of the sculpture with reflective decisions to achieve the desired results (Montgomery, 1999).

With this in mind, the practical reasoning approach involves three levels of knowledge (systems of action) that are based on each other in choosing a comprehensive solution to a “what should be done” problem: (more information will be provided in Chapter 2).

- Empirical knowledge, which is technical or scientific and produces technically useful knowledge, products, and procedures that describe or explain what is;

- Interpretive/Communicative knowledge, which creates a deep understanding of subjective experiences of individuals (perceptions, interpretations, feelings) and establishes a shared understanding and mutual agreement; and

- Critical/Reflective knowledge, which is focused on liberating people from false consciousness/misinformation and understandings, unjust/harmful systems, uncaring interactions, and harmful relationships, as well as empowering people to use rational and ethical reasoning to foster a just and humane society (McGregor, 2003).

The practical reasoning approach identifies and frames problems by encouraging the sharing of perspectives of those affected by a current situation that needs to change. This is done by avoiding jumping to quick solutions to the assumed problem; asking questions of others to gain an understanding; allowing oneself to be vulnerable in sharing honest thoughts and experiences without blaming others; addressing conflicts openly and respectfully; considering influences affecting the situation; and differentiating between facts and opinions (Vincenti & Smith, 2004).

The Critical Science Approach and a Common Language

With a profession that has been around for more than a century, there have been many changes to FCS, our society, and even the language that we use in our daily lives. Each change helps current and future educators, professionals, researchers, and others propel the FCS profession forward. This ensures that FCS professionals continue to meet the needs and demands of consumers where they are in the present time. For some, this textbook will be a reminder of the past and the excitement that FCS professionals can bring through new ideas and research. Others may find reading this textbook like a new language that is full of complexities, nuances, and vocabulary that should be practiced to effectively use a practical reasoning lens. There may even be some that notice the language the authors use to write this textbook may not be exact or identical to how the critical science approach was explained or written about in previous times. This was intentional when developing this textbook for a few key reasons. The language that was previously used in the FCS profession may not accurately capture the essence of critical thinking, practical reasoning, and the overall idea of the practical reasoning approach. Some phrases and terms were not consistent throughout written FCS literature, which was evident when reviewing journal articles for this textbook. A continuation of inconsistencies does not help the profession and instead, continues to cause potential confusion surrounding this very important topic. There is a small “ask”, for those who are familiar with the Critical Science Approach, while reading this book. See if the information challenges your knowledge and validates your opinions of critical thinking. How does the information presented allow you to expand upon your prior knowledge of the topic and how might that information be used to continue the conversation of critical thinking in your daily practice setting?

A lot of consideration was given to past research, current trends, and the society that we live in today when writing this textbook. It was also important that the history and philosophical foundations that FCS was built on were also considered and honored throughout this textbook. As mentioned earlier, change can be a positive thing for our profession. Hopefully, with this change, the textbook simplifies the language used that surrounds the Critical Science Approach and critical thinking.

The Practical Reasoning (Critical Science) Perspective and Its Connection to the Body of Knowledge of Family and Consumer Sciences

The Body of Knowledge of Family and Consumer Sciences

The Scottsdale Conference, held in 1993, was a major event in the history of FCS. The conference brought together educators, researchers, and practitioners from across the country to discuss the future of the field and to develop a shared vision for its growth and development (Nickols et al., 2009). The primary purpose of the Scottsdale Conference was to redefine the role and scope of FCS in the modern world. The field had been experiencing significant changes in the previous years, including the shift from “home economics” to “family and consumer sciences” and the need to address emerging issues such as globalization, changing demographics, and advances in technology (Nickols et al., 2009).

At the conference, participants engaged in a series of discussions and workshops focused on identifying the key challenges and opportunities facing FCS and developing a shared vision for its future. They also worked to define the core values and principles that should guide the field, such as a commitment to diversity and social justice, interdisciplinary collaboration, and a focus on the well-being of individuals, families, and communities (Nickols et al., 2009). The outcomes of the Scottsdale Conference were significant, as they helped to set a new direction for the field and to create a more cohesive and unified community of FCS professionals. The conference led to the development of the foundation for “Family and Consumer Sciences” and a Body of Knowledge that outlined the core knowledge and competencies needed for success in the field, as well as helped to position FCS as a dynamic and relevant profession capable of addressing the complex challenges facing modern society.

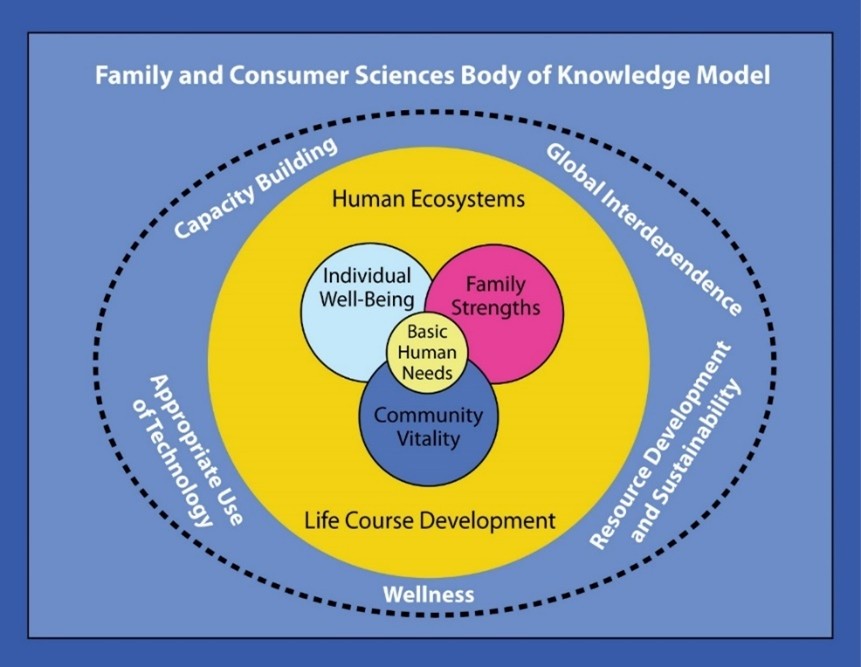

The FCS-BOK consists of three main categories: core concepts, integrative elements, and cross-cutting themes (Nickols et al., 2009). The core concepts include items that have a direct impact on what FCS professionals accomplish in helping individuals, families, and communities live in a complex and challenging world (AAFCS, 2023). At the center of this model is basic human needs, which include physiological needs, safety, love and belonging, self-esteem, and self-actualization (Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, 1968), which are undertaken by individuals, families, and communities.

Basic human needs interconnect in the FCS-BOK model with individual well-being, family strengths, and community vitality. Individual well-being was highlighted in the Brown and Paolucci (1979) mission of home economics, the building and maintaining of systems of action that lead to the “maturing in individual self-formation” (p. 23). The FCS profession focuses on individual well-being because stronger families and viable communities cannot happen without working with one individual at a time (Nickols et al., 2009). Family strengths include developing resilient families that enable them to deal with and recover from crises and transitions throughout the life of the family (Nickols et al., 2009). Community vitality is a group of individuals living in a geographic area that have common interests; thereby fostering a sense of belonging and connection within the community (Nickols et al., 2009). The FCS profession has been contributing to community vitality through its involvement in community service, community partnerships, and community education, to name a few.

Source: The Family and Consumer Sciences Body of Knowledge and The Cultural Kaleidoscope: Research Opportunities and Challenges. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077727X08329561

Now, adding a little more complexity, we move out to the integrative elements in the FCS-BOK model, which include human ecosystems and life course development. The integrative element of human ecosystems examines individuals and families concerning their natural (physical), human-built, and social/ behavior environments (Nickols et al., 2009). These environments can include transportation, availability of shelter, geographic weather patterns, employment opportunities, education, and food decisions, among others. FCS professionals can help individuals and families learn how to limit or change some of these environments, such as downsizing a house to save money, while other environments may be out of their immediate control, such as natural disasters like forest fires or tornadoes. The ability of individuals and families to use the practical reasoning perspective in making informed decisions on the various environments that will ultimately impact their well-being is essential throughout their life span.

The integrative element of life course development refers to changes in individuals and families that occur from birth through death (Nickols et al., 2009). These changes can include various personal events and transitions that are interconnected with other family members, which becomes a “collective” experience for the family (Nickols et al., 2009). For example, a family that has a history of working for a railroad company, but the company lays off its employees due to the current economy. The grandfather and father have always worked for the railroad and are very proud of their work and how they have supported their family. However, the youngest son decides he does not want to work for the railroad due to the career’s uncertainty and starts a new career as an executive chef. This career as a chef has allowed him to move to a different state, start a family, and participate in different cultural experiences. All these experiences are happening over the youngest son’s life span and will have direct impacts on meeting his basic human needs.

The outer areas of the FCS-BOK model include five cross-cutting themes: capacity building, global interdependence, resource development and sustainability, wellness, and appropriate use of technology. These cross-cutting themes are the trends and issues taking place in today’s dynamic changing environment (Anderson & Nickols, 2001). One of the cross-cutting themes having an impact on the FCS profession is capacity building. Capacity building is defined by Anderson and Nickols (2001) as “acquiring and using knowledge and skills, building on assets and strengths, respecting diversity, responding to change, and creating the future” (p. 11). The FCS profession is currently struggling to identify, recruit, and retain future FCS professionals from diverse backgrounds due to the continuous shortage of FCS educators at all education levels across the country. This shortage is occurring because FCS educators are not showing how the practical reasoning perspective can transform their learners, families, and communities through the interdisciplinary content they teach, which in turn, affects the impact on the identity of the profession.

Below are some examples of practical reasoning questions that can be developed directly from the FCS-BOK model:

- What should be done about wellness in this community if there is no clean drinking water?

- What should be done to mitigate forest fires in this community so that health services are uninterrupted?

- What should be done to ensure that the learner using adaptive technology at school has the same opportunity for using this technology at home?

Not all practical reasoning questions need to include words derived from the FCS-BOK model. These examples are to show the integrative nature of the FCS-BOK to the practical reasoning approach.

Currently, AAFCS developed a committee to review the FCS-BOK to ensure it remains relevant and applicable to today’s societal, technological, and global changes. Once this revised FCS-BOK is approved, this information will be updated in this chapter.

Connecting the FCS-BOK and the Practical Reasoning Perspective

Why is important to connect the FCS-BOK model to the practical reasoning perspective? As mentioned, the FCS-BOK is a theoretical framework that can help address both perennial and emerging problems for future research that can enhance the identity and visibility of the FCS profession. For example, the cross-cutting theme of resource development and sustainability is reflected in the current waste of food and clothing that are disproportionately affecting diverse populations across the world. We would apply the practical reasoning perspective to these two perennial problems by conducting a gap analysis to determine why they continue to persist in our society. Then we would look at the contextual factors affecting these perennial problems that are having an impact on diverse populations. After determining those factors, we would consider the goals or value-ends to be achieved in resolving these perennial problems as much as possible. Next, we would consider all of the solutions currently in place that may need to be revised or develop new solutions that would have a greater impact on these perennial problems given the current societal environment. Furthermore, we would look at all the short- and long-term consequences of these solutions before making reasoned and ethical judgments in resolving these perennial problems as much as possible on diverse populations. Lastly, we would take action by implementing these solutions to see how well they are impacting the problem. This would help ensure the FCS-BOK stays current and relevant.

Source: Family problems affecting the home. The authors developed this image using Tagxedo.

Application of Knowledge

Purpose: The purpose of this activity is to apply the FCS Body of Knowledge (FCS-BOK) to real-world perennial or emerging problems affecting individuals, families, and communities. By utilizing the practical reasoning perspective, you will identify a problem, analyze its causes, and develop strategies to address it using interdisciplinary FCS areas such as nutrition, parenting, human development, textiles, and personal finance, to name a few. This application aims to enhance overall well-being through informed decision-making and effective problem-solving.

Task: You will follow a structured approach to identify, analyze, and develop strategies for a perennial or emerging problem. The activity includes the following steps:

- Identify a Problem: Select a perennial or emerging problem affecting individuals, families, or communities. Examples include food insecurity, financial literacy, obesity, housing instability, or lack of access to quality education.

- Analyze the Problem: Research and discuss the reasons why this problem persists. Consider factors such as socioeconomic conditions, cultural influences, policy gaps, and environmental factors.

- Develop FCS-BOK Strategies: Based on your analysis, propose strategies to address the problem using the FCS-BOK. Include at least three different interdisciplinary areas of FCS in your strategy development.

Be sure to cite credible sources when you identify and analyze the problem.

Example Problem: Food Insecurity

Problem Identification: Food insecurity is a persistent issue affecting millions of families worldwide. It involves limited or uncertain access to adequate and nutritious food.

Problem Analysis: Food insecurity persists due to various factors such as poverty, unemployment, rising food prices, lack of access to healthy food options, and inadequate social support systems.

Developing Strategies Using FCS-BOK:

- Nutrition Education:

-

- Strategy: Implement community workshops to teach families how to prepare nutritious meals on a budget.

- Application: Use FCS principles of nutrition to create meal plans that maximize nutritional value while minimizing cost.

- Food Safety:

-

- Strategy: Offer training sessions on safe food handling and storage practices to reduce food waste and prevent foodborne illnesses.

- Application: Apply FCS knowledge of food safety to develop guidelines and educational materials for safe food practices.

- Resource Management:

-

- Strategy: Provide financial management workshops to help families develop budgeting skills and manage their resources more effectively.

- Application: Utilize FCS expertise in personal finance to create budgeting tools and resources that assist families in optimizing their finances.

- Community Partnerships:

-

- Strategy: Collaborate with local farmers and community organizations to increase access to fresh, healthy food.

- Application: Leverage FCS knowledge of community development to build sustainable food systems and promote local food initiatives.

References

American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences (AAFCS). (2023). What is FCS? https://aafcs.org/about/about-us/what-is-fcs

American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences Council for Accreditation. (2010). Accreditation documents for undergraduate programs in family and consumer sciences (2010 edition). https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/AAFCS/1c95de14-d78f-40b8-a6ef-a1fb628c68fe/UploadedImages/CredentialingCenter/AAFCS_Accreditation_Standards.pdf

American Chemical Society. (2021). Ellen H. Swallow Richards (1842-1911). https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/women-scientists/ellen-h-swallow-richards.html

Anderson, C. L., & Nickols, S. Y. (2001). The essence of our being: A synopsis of the 2001 Commemorative Lecture. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 93(5), 15-18.

Brown, M., & Paolucci, B. (1979). Home economics: A definition. American Home Economics Association.

Brown, Marjorie M. (1980). What is home economics education? Educational Resources Information Center. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED199546

Bubolz, M. M. (2002). Beatrice Paolucci: Shaping destiny through everyday life. Kappa Omicron Nu.

Clarke, R. (1973). Ellen Swallow: The woman who founded ecology. Follett Publishing Company, 1-276.

Cornell University. (2001). Ellen Swallow Richards: What was Home Economics? https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/homeEc/bios/ellenrichards.html

Freire, P. (1986). Pedagogy of the oppressed. 30th anniversary ed. Continuum International Publishing.

HaywoodWeavers. (2011, January). Ellen Swallow Richards [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GEI_l61eOzY

Levenstein, H. (1980). The New England kitchen and the origins of modern American eating habits. American Quarterly, 32(4), 369-386.

Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a psychology of being. D. Van Nostrand.

McGregor, S. (2003). Critical discourse analysis. A primer. Kappa Omicron Nu, 15(1). https://publications.kon.org/archives/forum/15-1/mcgregorcs.html

McGregor, S. (2014). Marjorie Brown’s philosophical legacy: Contemporary relevance. Kappa Omicron Nu FORUM, 19(1), 1-11.

Montgomery, B. (2008). Curriculum development: A critical Science perspective. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 26(National Teacher Standards 3), 1-16.

Montgomery, B. (2003). The critical science approach to reasoning for action in consumer education. The Journal of Consumer Education, 21, 1-11.

Montgomery. B. (1999). Chapter 7: Continuing concerns of individuals and families. In J. Johnson & C. Fedje (Eds.). Family and consumer sciences teacher education yearbook 19. Family and consumer sciences curriculum: Toward a critical science approach (pp. 80-90). Glencoe/McGraw Hill.

Nickols, S., Ralston, P., Anderson, C., Browne, L., Schroeder, G., Thomas, S., & Wild, P. (2009). The family and consumer sciences body of knowledge and the cultural kaleidoscope: Research opportunities and challenges. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 37(3), 266-283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077727X08329561

Science History Institute. (2021). Ellen H. Swallow Richards. https://www.sciencehistory.org/historical-profile/ellen-h-swallow-richards

Vincenti, V., & Smith, F. (2004). Critical science: What it could offer all family and consumer sciences professionals. Journal of Family & Consumer Sciences, 96(1), 63-70.