2 Practical Reasoning (Critical Science) Language

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to:

- Explain the concept of critical literacy, its importance in understanding social constructs, and its role in fostering democratic citizenship and ethical thinking.

- Identify and describe the five dimensions of critical literacy and how these dimensions enhance an individual’s ability to engage with societal issues.

- Differentiate between weak-sense and strong-sense critical thinking and evaluate your critical thinking habits to improve your intellectual humility, courage, empathy, integrity, perseverance, faith in reason, and sense of justice.

- Actively engage in critical reading by analyzing, interpreting, and evaluating texts, and recognize how texts communicate specific messages through various lenses and perspectives.

- Demonstrate critical writing skills by presenting well-structured arguments, engaging with evidence, recognizing the limitations of your sources, and considering multiple perspectives on a given issue.

- Practice critical speaking by effectively communicating arguments, integrating critical-thinking processes, and addressing internal assumptions and research processes in their speeches.

- Conduct critical self-reflection by identifying, questioning, and assessing your deeply held assumptions, beliefs, and perceptions, and how this reflection can lead to personal and professional growth.

- Define perennial problems and their significance in asking value questions about significant issues in everyday life, and apply practical reasoning to address these problems.

When Drs. Marjorie Brown and Beatrice Paolucci developed the practical reasoning approach, this began the development of a language that reflected new ideas to help individuals think, reason, interpret, and take action through the study of recurring, practical problems. This language also recognized the need for the integration of multiple types of knowledge to best serve individuals and families. Therefore, this chapter will define critical literacy (or critical consciousness) and the five dimensions associated with developing strong critical literacy skills. It will also define concepts in practical reasoning associated with perennial problems affecting individuals and families and concepts associated with the practical reasoning process framework to address individual and family concerns. The practical reasoning language helps Family and Consumer Sciences (FCS) professionals break out of the cycle of just transmitting knowledge, and take action to transform themselves, their families, and their situations (Rehm, 1999). This language also helps individuals reframe their thinking to see the many possibilities or alternatives: What could be, vision, goals, imagination, and enthusiasm, among others. Simon & Dippo (1987) stated that the “critical science language must be defined by its significance in relation to the project of expanding human possibilities” (p. 108). Becoming familiar with practical reasoning language is about helping individuals free themselves from oppression in order for them to see the potential they have to make their own well-informed decisions as they participate in society (Rehm, 1999).

Critical Literacy (or Critical Consciousness)

What is “critical literacy”? It examines the relationship between language and power in various texts in a manner that promotes a deeper understanding of socially constructed concepts, such as inequality and injustice in human relationships (Shor, 1999). Shor further emphasizes:

“Critical literacy . . . points to providing learners not merely with functional skills, but with the conceptual tools necessary to critique and engage society along with its inequalities and injustices. Furthermore, critical literacy can stress the need for learners to develop a collective vision of what it might be like to live in the best of all societies and how such a vision might be made practical” (Macrine, 2009, p. 120).

This includes examining texts that involve printed books, magazines, and comic books, as well as videos, websites, street signs, public transport messages, graffiti or billboards, and music, to name a few. All texts are created from a particular lens, frame, or perspective to convey specific messages. Critical literacy encourages individuals to understand and question the attitudes, values, and beliefs of written texts, visual applications, and spoken words. These communication methods are then used to equip individuals with a critical stance, response, or action toward an issue.

Critical literacy moves the reader’s focus away from the “self” in critical reading to the interpretation of texts in different environmental and cultural contexts (Rehm, 1999). This means when individuals engage in critical literacy, they are prepared 1) to make informed decisions regarding issues such as power and control; 2) to engage in the practice of democratic citizenship; and 3) to develop an ability to think and act ethically; thereby, becoming agents of change. Five dimensions that will enhance an individual’s critical literacy skills are critical thinking, reading, speaking, writing, and self-reflection.

Critical Thinking

What is “critical thinking”? It is a technique for evaluating information and ideas, for deciding what to accept and believe (Browne & Keeley, 2018). Critical thinking also begins with the desire to improve what we think. Further, critical thinking is normally a trained reaction to what others are saying and writing. There are two approaches to critical thinking where we are either defending or evaluating and reconsidering our initial beliefs: weak-sense critical thinking and strong-sense critical thinking (Browne & Keeley, 2018).

Individuals using the weak-sense critical thinking approach will only look for evidence that strengthens their position and weakens their opposition (Browne & Keeley, 2018). Because this kind of thinking is not concerned with truth or virtue, it has the potential to ruin the civilized and progressive aspects of critical thinking (Browne & Keeley, 2018). How do you know if you are a weak-sense critical thinker? First, do you tend to start with a position that you already “know” is true and then look for reasons that support it? This is called rationalizing and is backward from the proper reasoning method. Second, do you find your evidence by only looking to sources that will agree with you? Third, do you tend to ignore criticisms of your position or become very defensive? Fourth, do you mentally suppress evidence that might make your opposition look good? Lastly, are you unwilling to change your mind about things, even when presented with research-based evidence?

Individuals using the strong-sense critical thinking approach will see no point in winning an argument if there is evidence to believe the position being argued is strong (Browne & Keeley, 2018). This type of critical thinker is aware that learning is an internal transformation of a person’s mind and character, a transformation that can only occur when thinking is done fairly and properly. They would be able to find strong evidence supporting one position and the weaknesses in the other, but they would also be willing to seek out strong evidence for the opposition and the weaknesses in their current position (Browne & Keeley, 2018). In other words, it requires admitting upfront the possibility that whatever is currently believed to be true could be false. It requires one to seek out the very best evidence for all sides of an issue. Then it requires accepting the conclusion that is supported best by the evidence. Strong sense critical thinkers seek truth and virtue and are willing to accept they are wrong given the appropriate evidence (Browne & Keeley, 2018). The characteristics of strong-sense critical thinkers include intellectual humility, intellectual courage, intellectual empathy, intellectual integrity, intellectual perseverance, faith in reason, and an intellectual sense of justice (Browne & Keeley, 2018). How do you know if you are a strong-sense critical thinker? First, based on the list of characteristics above, how many of them describe you? Second, can you think of examples where you used to believe one thing, then through your own initiative researched a subject and realized the only intellectually honest thing to do was to change your mind? Third, can you say you did this when you had a vested interest in holding the first position? Lastly, do you have a genuine sense of curiosity regarding the beliefs of others?

Source: How to Develop the 7 Skills of Critical Thinking (https://www.brightconcept-consulting.com/en/blog/leadership/how-to-develop-the-7-skills-of-critical-thinking)

Being a critical thinker is difficult because we are under persistent assault by others who want to tell us what to believe, what choices to make, and how to live. Second, thinking carefully is not admired. Often the conclusions critical thinkers arrive at are not popular conclusions. Third, it takes time. You need to find evidence, weigh the evidence, and be honest. Fourth, true critical thinking is threatening to the ego. Critical thinkers must exercise intellectual humility. As strong-sense critical thinkers, we should pursue better conclusions, better beliefs, and better decisions (Browne & Keeley, 2018).

Critical Reading

What is “critical reading”? It is actively engaging in the process of analyzing, interpreting, and sometimes, evaluating what is being read – that is, not taking anything read at face value (Kurland, 2000). Critical reading and critical thinking work together in actual practice. If we sense statements we are reading as unreliable or ridiculous (critical thinking), then we examine the text more closely to test our understanding (critical reading). “Critical readers thus recognize not what a text says, but also how that text portrays the subject matter” (Kurland, 2000). Below is a table of the differences between “reading” and “critical reading.”

| READING | CRITICAL READING | |

| Purpose | To get a basic grasp of the text. | To form judgments about how a text works |

| Activity | Absorbing/Understanding | Analyzing/Interpreting/Evaluating |

| Focus | What a text says | What a text does and means |

| Questions | What is the text saying?

What information can we get out of it? |

How does the text work? How is it argued?

What are the choices made? What are the patterns that resulted? What kinds of reasoning and evidence are used? What are the underlying assumptions? What does the text mean? |

| Direction | With the text (taking for granted it is right) | Against the text (questioning its assumptions and argument, interpreting meaning in context) |

| Response | Restatement, Summary | Description, Interpretation, Evaluation |

Source: The Writing Centre, University of Toronto Scarborough

Critical reading begins the process of taking action. We are not simply absorbing the information; instead, we are interpreting, categorizing, questioning, and weighing the value of that information. In other words, we are engaged in higher-order thinking.

Five steps to critically read and improve our critical thinking of a text (Shor, 1999):

- Determine the specific topic or purpose of the text (its thesis). A critical reader attempts to assess how this topic or purpose is developed or argued.

- Make some judgments about the context. What audience is the text written for? Who is it in dialogue with? (This will probably be other scholars or authors with differing viewpoints.) In what historical context is it written? All these matters of context can contribute to an individual’s assessment of what is going on in a text.

- Distinguish the kinds of reasoning the text employs. What terms are defined and used? Does the text appeal to a theory or theories? Is any specific methodology laid out? If there is an appeal to a particular concept, theory, or method, how is that concept, theory, or method then used to organize and interpret the data? We might also examine how the text is organized: how has the author analyzed (broken down) the material? Be aware that different disciplines will have different ways of arguing.

- Examine the evidence (the supporting facts, examples, etc.) the text presents. Supporting evidence is indispensable to an argument. Having worked through Steps 1-3, we are now able to grasp how the evidence is used to develop the argument and its controlling assertions and concepts. Steps 1-3 allow us to see evidence in its context. Consider the kinds of evidence that are used. What counts as evidence in this argument? Is the evidence statistical? literary? historical? etc. From what sources is the evidence taken? Are these sources primary or secondary?

- Critical reading may involve evaluation. Our reading of a text is already critical if it accounts for and makes a series of judgments about how a text is argued. However, some texts may also require you to assess the strengths and weaknesses of an argument. If the argument is strong, why? Could it be better or differently supported? Are there gaps, leaps, or inconsistencies in the argument? Is the method of analysis problematic? Could the evidence be interpreted differently? Are the conclusions warranted by the evidence presented? What are the unargued assumptions? Are they problematic? What might an opposing argument be?

As critical readers, we want to assure ourselves that these steps have been completed in a comprehensive and consistent manner. Once we have determined that a text is comprehensive and consistent, then we can begin to evaluate whether to accept the arguments and conclusions. Reading to see what a text says may be sufficient when the goal is to learn specific information or to understand someone else’s ideas, but we normally read for other purposes.

Critical Writing

What is “critical writing”? It is learning how to present all sides of an effective argument (Ahmed, 2018). This means learning how to present the reasoning and evidence in a clear, well-structured manner. The aim of critical writing is not to present the “right answer,” but to discuss the arguments intelligently (Ahmed, 2018). Example activities of critical writing include:

1) engaging with the evidence;

2) open-minded and objective inquiry;

3) presenting reasons to dispute a particular finding;

4) providing an alternative approach;

5) recognizing the limitations of evidence; either your evidence or the evidence provided by others;

6) thinking around a specific problem; and

7) applying caution and humility when challenging established positions.

Critical writers show their interpretation of the evidence and source material, how they have used that information to demonstrate their understanding and their subsequent position on the topic. Critical writing is involved in academic debates and researching what is happening in a subject area (Ahmed, 2018). The way critical writers select their sources, the way they show how they agree or disagree with other pieces of evidence and the way they structure an argument will all show their thought process and how they have understood the information they have read.

Critical writers keep their readers in mind and try to anticipate the questions they would ask. They can use evidence to help them strengthen their position, answer readers’ questions, and counteract opposing points of view.

Critical Speaking

What is “critical speaking”? It is communicating an argument effectively by integrating fully into the critical-thinking process (Wagner, 2019). When critical speakers address, theorize, examine, explain, and review their work, then they are thinking critically. Learning to speak critically helps individuals address internal assumptions and the research process. Like the information provided in the Critical Reading and Critical Writing sections of this chapter, critical speakers need to ask the following questions when they put an argument together (Wagner, 2019):

- Purpose – What is the purpose/goal/intent/outcome you are trying to accomplish in your speech? What do you want the audience to know, think, feel, or do when you are done with the speech?

- Question – What question are you addressing? What are the needs of your listeners?

- Information – What information are you providing to support your goal and purpose? What experience do you bring to the topic, method, and goal?

- Concepts – What are the concepts you want your listeners to understand? Are they clear? Are they relevant? Do they make sense?

- Assumptions – What assumptions have you made about your listeners, their knowledge level, their interest, and their needs? Are your assumptions valid? Are you taking your listeners for granted? How can you answer the listeners’ questions or assumptions?

- Inferences – Have you reasoned out all aspects and lines of thinking in presenting your evidence? What is your support for the inferences and suggestions you are making in your speech? Have you evaluated the sources you will use for support?

- Points of View – Do you acknowledge, allow, and respect other points of view from your listeners? In the speech-building stages, do you incorporate these opposing views? How do you respond to other points of view?

- Implications – Do I understand the ramifications and results of the position and goal you are presenting in your speech? How can you incorporate the pieces of information as you progress as a speechwriter and presenter for critical thinking for public speaking?

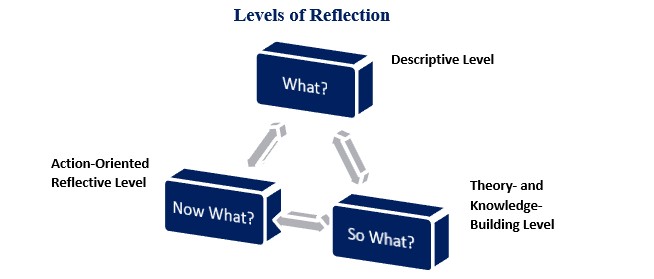

Critical Self-Reflection

What is “critical self-reflection”? It refers to the process of identifying, questioning, and assessing our deeply held assumptions, beliefs, and perceptions that have led to personal growth and how we might think or act differently in the future as a result (Bart, 2011; Jacoby, 2010). The goal of critical self-reflection is to change your thinking about a subject and thus change your behavior. It is a vehicle for critical analysis, problem-solving, synthesis of opposing ideas, evaluation, identifying patterns, and creating meaning (Rehm, 1999).

Critical self-reflection is a form of personal and professional learning and development that involves thinking about practices and procedures with intent and honesty. It needs to be embedded in daily practice and can be a challenging skill requiring the ability to question and change deep-seated assumptions and practices (Bart, 2011; Jacoby, 2010). Critical reflection begins by engaging with our thoughts, feelings, and experiences on what is occurring within a particular environment (e.g., home setting, work setting, etc.) and thoroughly analyzing the assumptions that reinforce our perceptions.

The next step is to accept different viewpoints to learn and evaluate how we may change our approach or perspective on an issue or problem. This can lead to new conclusions and possible solutions with new ideas to inform future planning and actions. The idea is that we not only explore our reaction to an issue or problem but we are also examining that issue or problem from alternative viewpoints, such as through the eyes of a colleague or by reviewing relevant literature and theories and considering if a change is required in our approach or perspective.

Critical self-reflection involves:

- Reflecting on our own biases;

- Examining and rethinking our perspectives;

- Questioning whether our perspectives take a broad view;

- Considering all aspects of an issue or problem;

- Engaging in thought-provoking conversations with colleagues, families, professionals, and community members; and

- Using reflective questions in the critical science perspective to prompt our thinking.

When working with learners, as an example, educators are compelled to constantly reflect on their practice and how it influences learners’ worldviews. In turn, Family and Consumer Sciences (FCS) educators should develop reflection assignments and discussions requiring learners to examine their attitudes and practices (Rehm, 1999). This reflective thinking by learners will further help them see any issues within themselves that interfere with their independence and ability to make reasoned decisions.

Critical self-reflection is important because it ensures the best possible outcomes occur with the individuals we work with and live with daily. The benefits of engaging in critical self-reflection include (Bart 2011; Jacoby, 2010):

- Strengthening our personal and professional practice;

- Generating learning;

- Engaging higher-order thinking and creative practice;

- Helping individuals make sense of experience;

- A vehicle for problem-solving;

- Allowing the development of deeper understandings; and

- Building valuable insights to inform decision-making and manage issues more effectively.

Critical self-reflection provides a framework to think differently about working through various issues or problems and helps us make purposeful changes to our practice for improving personal and professional outcomes.

Perennial Problems

Perennial is defined as situations or states that keep occurring or that seem to exist all the time; used specifically to describe perennial problems such as unemployment being a perennial cause of poverty (Brown and Paolucci, 1979). Perennial problems are concerned with asking value questions about “how-to” and “what should be” regarding significant issues in everyday life (Brown & Paolucci, 1979).

Browne and Keeley (2018) explain “how-to” problems as descriptive problems “that raise questions about the accuracy of descriptions of the past, present, and future” (p. 17). Example descriptive questions include the following:

- Does financial education improve a person’s ability to budget their money?

- What ought to be done about the $1.7 trillion learner loan debt crisis?

- Is cognitive behavioral therapy the most effective way to treat depression?

They require answers attempting to describe the way the world was, is, or is going to be. The answers to these types of problems are commonly found in textbooks, magazines, the Internet, and television. “How-to” problems are technical problems that include a step-by-step process toward one solution. Other examples of “how-to” problems include completing a job application to achieve the goal of receiving an interview; or how to follow directions on a recipe to achieve the goal of producing an edible product; or how to sew in achieving the goal of producing a clothing item (Montgomery, 1999). The “how-to” problem is solved when specific steps are followed to achieve the goal or complete the product.

Browne and Keeley (2018) also explain “what should be” problems as prescriptive problems “that raise questions about what should be done or what is right or wrong, or good or bad” (p. 18). Example prescriptive questions include the following:

- Should food insecurity be taught in public schools?

- What should be done to reduce child obesity?

- Must we outlaw specific apps used in social media to reduce the increasing rates of eating disorders among adolescents?

They require answers that address the search for achieving particular conditions within society such as equality, freedom, or security. Because these questions search for specific conditions, they are considered perennial problems, which need to be continually reevaluated (Montgomery, 1999). Perennial (what should be) problems are value-related problems that do not come with a prescribed (how-to) solution. The solution may require choices between competing goals and values (Montgomery, 1999). For example, loyalty and honesty are competing values that shape an individual’s conclusion to a problem concerning a particular controversy, such as “Should you tell your parents about your sister’s drug habit?” The solution may include multiple perspectives, conditions, or contextual aspects related to the problem. An understanding of what currently exists related to the problem is needed to develop solutions, as well as the historical, political, economic, cultural, and gender-related aspects, to name a few (Montgomery, 1999).

One of the strategies that can be used to examine perennial or emerging problems is conducting a gap analysis. A gap analysis is an examination and assessment of a recurring concern to identify the differences between “what is” (what currently exists regarding the problem) and “what should be” (that which is more desirable) and how to close the gap between the two (Brown, 1980). There are three steps needed when conducting a gap analysis:

- Identify the main perennial or emerging problem – this initial step is to understand where we want to apply a gap analysis, and what we seek to get out of it;

- List the symptoms of the problem by breaking down the problem into specific, observable symptoms or sub-issues through research. A symptom of a problem is something you can see or feel that shows there is a bigger issue. It is a sign or effect caused by the main problem. Symptoms help us understand how the problem affects individuals, families, and communities; and

- For each symptom, create a set of questions that will help explore and understand the underlying causes and contributing factors.

With these three steps in mind, you can effectively analyze and address other perennial problems in a similar manner. An example is provided below:

Perennial Problem: What should be done to ensure all families can afford childcare?

Symptoms of the Problem Through Research:

- High costs for families

- Limited availability of childcare centers

- Low wages for childcare workers

- Impact on workforce participation

- Variable quality of care

Questions for Each Level of the Gap Analysis:

High Costs for Families:

- What are the average costs of childcare in different regions?

- How do childcare costs compare to average family incomes?

- What percentage of family income is typically spent on childcare?

- Are there any existing subsidies or financial assistance programs for childcare?

Limited Availability of Childcare Centers:

- What is the current supply of childcare centers in various regions?

- What are the waitlist times for enrollment in childcare centers?

- Are there any geographical areas with a higher concentration of childcare centers?

- What are the regulatory barriers to opening new childcare centers?

Low Wages for Childcare Workers:

- What are the average wages for childcare workers?

- How do these wages compare to the cost of living in different areas?

- What are the qualifications and training requirements for childcare workers?

- How does low pay affect worker turnover and the quality of care provided?

Impact on Workforce Participation:

- How does the cost of childcare affect parents’ decisions to enter or remain in the workforce?

- Are there particular demographics more affected by childcare costs (e.g., single parents, low-income families)?

- What policies or programs are in place to support working parents with childcare needs?

- How does the lack of affordable childcare impact employers and overall economic productivity?

Variable Quality of Care:

- What standards and regulations are in place to ensure the quality of childcare?

- How is the quality of childcare measured and monitored?

- What are the differences in quality between various types of childcare providers (e.g., home-based vs. center-based)?

- How do parental perceptions of childcare quality influence their choices and satisfaction?

After completing this type of gap analysis, the results should be a detailed understanding of the main problem and its various symptoms. This understanding helps in several key ways:

- Identification of Key Issues: Clearly identifying the main problem and its symptoms gives a comprehensive view of what needs to be addressed.

- Prioritization: Understanding the different symptoms helps in prioritizing which issues need immediate attention and which can be addressed later.

- Root Cause Analysis: The questions asked for each symptom guide the analysis to uncover the underlying causes of the problem.

- Actionable Insights: The analysis provides actionable insights and information that can be used to develop targeted solutions and interventions.

- Informed Decision-Making: With a clear picture of the problem and its effects, stakeholders can make informed decisions about where to allocate resources and efforts.

By the end of this gap analysis, there should be a clear path forward with specific steps to address the main problem and its symptoms, leading to more effective and targeted interventions.

Conducting this type of gap analysis on perennial problems offers several benefits:

- Enhanced Understanding of the Problem

- Comprehensive Insight: By breaking down the main problem into its symptoms, you gain a detailed understanding of the various aspects and dimensions of the issue.

- Root Cause Identification: Helps identify the underlying causes of the problem, not just the visible symptoms.

- Informed Decision-Making

- Data-Driven Decisions: Provides a solid foundation of data and insights, enabling stakeholders to make informed and strategic decisions.

- Prioritization: Helps prioritize issues based on their impact, allowing for more efficient allocation of resources.

- Targeted Solutions

- Actionable Steps: Identifies specific areas that need intervention, leading to the development of targeted solutions and action plans.

- Focused Efforts: Ensures that efforts are directed towards the most pressing issues, increasing the chances of successful outcomes.

- Resource Optimization

- Efficient Use of Resources: Helps allocate resources more effectively by focusing on areas that will have the most significant impact.

- Cost Savings: Reduces waste by avoiding unnecessary actions and focusing on critical areas.

- Improved Stakeholder Engagement

- Clear Communication: Provides a clear and structured way to communicate the problem and its impacts to stakeholders.

- Collaboration: Facilitates collaboration among different stakeholders by highlighting areas where joint efforts are needed.

- Proactive Problem-Solving

- Prevention of Escalation: By addressing symptoms early, prevents the problem from escalating and causing more significant issues.

- Continuous Improvement: Encourages ongoing monitoring and evaluation, leading to continuous improvement and adaptation of strategies.

- Better Policy and Program Development

- Evidence-Based Policies: Supports the creation of policies and programs based on thorough analysis and evidence.

- Tailored Programs: Enables the development of programs that are specifically tailored to address the identified needs and gaps.

Example: Benefits in the Context of Affordable Childcare

- Understanding High Costs: Identifies why childcare is expensive and explores potential financial assistance options.

- Addressing Availability: Highlights regions with a shortage of childcare centers, guiding efforts to increase availability.

- Improving Wages: Recognizes the need for better wages for childcare workers to reduce turnover and improve care quality.

- Supporting Workforce Participation: Identifies the impact of childcare costs on parents’ ability to work, informing policies to support working families.

- Ensuring Quality: Focuses on improving the quality of care across different providers through better standards and monitoring.

Conducting this type of gap analysis is a powerful tool for systematically understanding and addressing complex problems, leading to more effective and sustainable solutions.

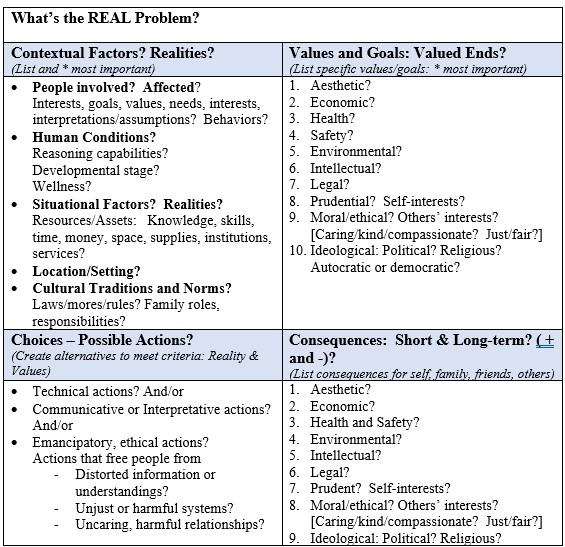

Practical Reasoning

Perennial or emerging problems are solved by engaging in the practical reasoning process. This process includes identifying and clarifying the context of the problem, examining valued ends, considering alternative means, comparing consequences, and taking action to promote positive qualities and actions (Brown & Paolucci, 1979).

The first step of this process is to identify and clarify the perennial or emerging problem. This includes asking individuals and families what existing gaps or needs are noticeable in their environment that can be used to challenge their assumptions (Klemme & Rommel, 2003). Once a perennial or emerging problem is identified, the question of “what should be done” is asked to help individuals and families focus on the research related to the problem.

The second step is to apply our critical literacy skills to examine meanings, values, valued ends, and other information related to the perennial or emerging problem. Valued ends are “the desirable state of affairs that individuals and families can achieve by examining existing conditions, reflecting on alternative options and choices, and acting to improve their lives” (Rehm, 2021, p. 187). Examples of valued ends include the well-being of individuals and families; democratic ideals; healthy nutrition; clean and sanitary conditions; a safe environment; and fairness and equity, to name a few (Laster, 2008). This is where we can begin comparing the existing conditions of “what is” with the ideal conditions of “what should be.” Three action concepts describe possible means for achieving valued ends. Individuals making decisions usually need three strategies for action (Laster, 2008):

- Technical action gets things done in the home, family, and community where private or public caregiving is necessary for quality of life. For example, planning, preparing, and serving food; selecting and caring for living environments and clothes; and maintaining safe, clean, and sanitary conditions (pp. 4-5).

- Communicative/Interpretive action calls for interpreting communications from diverse individuals in our complex world and relating to others in caring, supportive ways. For example, clarifying values, educating, advocating, dialoguing, and collaboratively solving problems (pp. 4-5).

- Reflective/Emancipatory action changes situations that interfere with healthy development, productivity, and autonomy with responsibility. For example, critiquing present social conditions, and forming individual and social goals and means for accomplishing change; collaboratively creating rules and laws, policies, and practices; and changing personal or family practices to meet the needs of family members or to promote the common good of others in society (pp. 4-5).

The third step is to evaluate the personal context of the perennial or emerging problem (Rehm, 2021). This is so we can become more critically conscious of our internal factors to make necessary changes, utilize our strengths, and work to become more empowered (Rehm, 2021). Individual barriers could include vague assumptions, personal biases, doubts, fears, weaknesses, or gaps in knowledge and skills (Rehm, 2021). Individual strengths could include skills, interests, guiding values, persistence, special knowledge, and life experiences (Rehm, 2021). We should be asking questions like: “Where am I in terms of reaching the valued end? What does it mean for me? What are my taken for granted assumptions? What am I doing that is getting in the way of reaching the valued end?” (Rehm, 2021, p. 191). This step engages critical self-reflection.

The fourth step “focuses on guiding individuals and families in analysis and critique of social trends, cultural influences, economics, political systems, and other external factors that affect their families” (Rehm, 2021, p. 191). This is where individuals and families can see how society affects them and what they can do to have an impact on society (Rehm, 2018). As we begin to understand others based on their perspectives, as well as research, we can start to compare possible alternatives and outcomes.

The fifth step is to analyze alternative ways to achieve the valued ends and the possible consequences of each alternative (Rehm, 2021). “Consequences concepts describe the results of holding a particular valued-end, or of actions proposed and taken. Individuals examine both primary and secondary consequences—how they are affected and how others will be affected now and in the future” (Laster, 2008, p. 5):

- Consequences of technical actions for self and others, such as effects of a low protein diet on the brain development of the fetus during the third trimester of pregnancy, and ultimately on the parents and society; effects of television on the development of children, and ultimately on cultural norms (Laster, 2008, p. 5).

- Consequences of communicative actions for self and others, such as probable effects of quitting a job without giving employer notice; effects of clarifying values; effects of education; effects of collaboratively addressing problems versus individually addressing problems (Laster, 2008, p. 5).

- Consequences of reflective emancipatory actions on self and others, such as probable effects of raising the consciousness of cultural norms regarding domestic abuse; effects of laws on reducing child abuse; effects of uncovering the root causes of alcoholism, codependency, and confronting alcoholism among peers and families; effects of dominating and supportive relationships on the quality of life and development of young children; and effects of well-developed reasoning versus inadequate reasoning on relationships and quality of life (Laster, 2008, p. 5).

We would begin asking questions such as “What is one alternative to change the situation, with what means, and with what consequences?” “What is the second alternative, with what means, and with what consequences?” (Rehm, 2021, p. 192). As the example table previously showed on the rising household debt within families, one alternative might be to require families with significant household debt to seek consumer credit counseling to better understand why and how they must live within their financial means. Various means could be meeting with a consumer credit counselor within a community agency, church, or online. A positive consequence would be families that participate will implement evidence-based budgeting and saving strategies to reduce their household debt and increase their emergency savings within a specified time frame. However, this would only help families who meet with a consumer credit counselor and follow his/her strategies for reducing their household debt.

The last step is to “create a plan of action, take action, and evaluate the action” (Rehm, 2021, p. 192). The goal would be to empower the individual and family to work together to create a valued end. Once the action plan is implemented, you would need to evaluate the effects on families: Have families reduced their household debt within the specified time frame as a result of meeting with the consumer credit counselor? Have families seen an increase in their quality of life as a result of reducing their household debt?

In summary, the practical reasoning process is the ability of people, either individually or collectively, to ethically reason about a course of action needed on a practical perennial or emerging problem (Laster and Johnson, 1998). Ethical thinking is also needed because practical reasoning involves both judgments of fact and judgments of value (Olson, 1999). Below is a Practical Reasoning Process Think Sheet strategy to help outline each of the steps individuals and families can use to develop specific critical literacy habits.

PRACTICAL REASONING: Deciding What’s Best To Do . . .

QUESTION . . . TEST! WHICH CHOICE IS BEST?

Evaluate! Test! Which alternative action(s) are…

___ Workable for situation . . .for reality?

___ Best for the well-being of self AND others . . long term? family? community?

and those different from me/you? world?

___ Based on reliable, adequate information and evidence?

___ Meets my/our criteria for best choice?

Critical Reflection – Judgments:

- What are our obligations and responsibilities in this situation?

- What persuasive reasons best support my/our conclusion?

Do the facts and values, especially moral/ethical values, support this choice?

-

- How will this affect others? Those different from me? Now? Future? Fairly? Unfairly?

- Would I/you want to be the person adversely affected?

- What if everyone did this? Negative? Positive?

- What are the contradictions or discrepancies? False assumptions? Differing assumptions?

Decision – What is the Best Choice?

Reasons: 1. 2. 3.

Note: The Practical Reasoning Process Think Sheet developed by Fox (1997), Laster (2008), and Montgomery (1999, 2008) was revised by Dr. J. Laster in 2021 in preparation for the AAFCS Critical Science Academy.

Application of Knowledge

Purpose: The best way to learn practical reasoning is to “do practical reasoning.” Thus, the purpose of this activity is to apply the practical reasoning process to identify, analyze, and propose solutions to a perennial problem affecting individuals and families, while developing critical literacy, critical thinking, and reflection skills.

Tasks:

- Problem Identification (15 minutes):

- Divide participants into small groups.

- Each group selects a perennial problem from a list provided (e.g., affordable childcare, food insecurity, household debt) or brainstorms a new one.

- Groups use the practical reasoning framework to clarify the problem’s context, including identifying “what is” versus “what should be.”

- Critical Literacy Application (20 minutes):

- Groups review a curated set of texts (e.g., news articles, policy briefs, case studies) related to their chosen problem.

- Analyze the language, perspectives, and power dynamics present in the texts using the five critical literacy dimensions: critical thinking, reading, speaking, writing, and self-reflection.

- Groups discuss how these texts shape their understanding of the problem.

- Gap Analysis and Values Discussion (20 minutes):

- Conduct a gap analysis to identify the root causes, symptoms, and contributing factors of the problem.

- Discuss relevant values (e.g., fairness, safety, health) and determine the “valued ends” that the group aims to achieve.

- Solution Design and Consequence Analysis (30 minutes):

- Brainstorm multiple possible actions (technical, communicative, and emancipatory) to address the problem.

- Evaluate the potential consequences (positive and negative) of each proposed action for individuals, families, and society.

- Choose the best course of action based on evidence and group consensus.

- Critical Reflection and Presentation (15 minutes):

- Reflect on the reasoning process by answering critical questions:

- What assumptions did we challenge?

- How did diverse perspectives influence our decision?

- What did we learn about our own biases and values?

- Each group presents their analysis and proposed solution to the class.

- Reflect on the reasoning process by answering critical questions:

- Debrief (10 minutes):

- Facilitate a discussion about the overall activity:

- What insights did participants gain about practical reasoning and critical literacy?

- How can this process be applied in real-world scenarios?

- Facilitate a discussion about the overall activity:

References

Ahmed, K. (2018). Teaching critical thinking and writing in higher education: An action research project. Teacher Education Advancement Network Journal, 10(1), 74-84.

Bart, M. (2011). Critical reflection adds depth and breadth to learner learning. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-and-learning/critical-reflection-adds-depth-and-breadth-to-learner-learning/

Brown, M. (1980). What is home economics education? University of Minnesota.

Brown, M., & Paolucci, B. (1979). Home economics: A definition. American Home Economics Association.

Browne, M. N., & Keeley, S. M. (2018). Asking the right questions: A guide to critical thinking (12th ed.). Pearson.

Fox, C. K. (1997). Incorporating the practical problem-solving approach in the classroom. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 89(2), 37-40.

Jacoby, B. (2010). How can I promote deep learning through critical reflection? Magna Publications. https://www.magnapubs.com/product/program/how-can-i-promote-deep-learning-through-critical-reflection/

Klemme, D. K., & Rommel, J. I. (2003). Exploring the state of poverty: A classroom experience. Kappa Omicron Nu FORUM, 14(20). https://www.kon.org/archives/forum/14-2/forum14-2_article2.html.

Kurland, D. J. (2000). What is critical reading? http://www.criticalreading.com/critical_reading.htm.

Laster, J. F. (2008). Curriculum handbook: Family and consumer sciences. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. http://www.ascd.org/publications/curriculum-handbook/404/chapters/Principles-of-Teaching-Practice-in-Family-and-Consumer-Sciences-Education.aspx.

Laster, J. F., & Johnson, J. (1998). Curriculum handbook: Family and consumer sciences. Association for Curriculum and Development.

Macrine, S. (2009). Chapter 6: What is critical pedagogy good for? An interview with Ira Shor. Critical Pedagogy in Uncertain Times: Hopes and Possibilities. Palgrave Macmillan.

Montgomery, B. (2008). Curriculum development: A critical science perspective. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences Education, 26(National Teacher Standards 3), 1-16.

Montgomery, B. (1999). Chapter 7: Continuing concerns of individuals and families. Family and Consumer Sciences Curriculum: Toward a Critical Science Approach (Yearbook 19), 80-90. Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

O’Connor, M. O. (n.d.). What is the difference between reading and critical reading? The Writing Center, University of Toronto Scarborough. https://www.stetson.edu/other/writing-program/media/CRITICAL%20READING.pdf.

Rehm, M. (2021). Chapter 3: The critical science approach, perennial problems, practical reasoning, and developing critical thinking skills. Teaching Family and Consumer Sciences in the 21st Century (3rd Ed.), 1-26. The Curriculum Center for Family and Consumer Sciences.

Rehm, M. (1999). Chapter 5: Learning a new language. Family and Consumer Sciences Curriculum: Toward a Critical Science Approach (Yearbook 19), 58-69. Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Shor, I. (1999). What is critical literacy? Journal for Pedagogy, Pluralism, & Practice, 4(1). https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/jppp/vol1/iss4/2/.

Simon, R. & Dippo, D. (1987). What schools can do? Designing programs for work education that challenge the wisdom of experience. Journal of Education 169(3), 110-116.

Wagner, P. E. (2019). Reviving “thinking” in a “speaking” course: A critical-thinking model for public speaking. Communication Teacher, 33(2), 158-163.