7 Exploring Real-Life Concerns: Scenarios, Case Studies & Role Plays

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to:

- Analyze practical, real-life problems using scenarios, case studies, and role plays, identifying technical, communicative, and reflective aspects to propose actionable solutions.

- Apply the Practical Reasoning Framework to determine valued ends and make ethical and justifiable decisions that consider both short- and long-term consequences for individuals and communities.

- Integrate content knowledge from multiple disciplines with process skills to address complex, authentic problems impacting families and communities.

- Enhance critical thinking skills, including autonomy, curiosity, humility, and respect for good reasoning, while engaging in moral reasoning to explore the implications and consequences of choices.

- Practice perspective-taking and empathetic listening by exploring diverse values, attitudes, and beliefs in scenarios and role-play activities.

- Engage in collaborative inquiry to develop, evaluate, and prioritize solutions, using a question-driven approach that challenges personal assumptions and explores diverse perspectives.

- Evaluate internal and external constraints, including personal biases and social forces, to understand the influence of power and advocate for equitable actions in addressing practical problems.

A curriculum developed using the Practical Reasoning (critical science) Approach aims to prepare individuals and families to take reasoned and justifiable action when addressing practical perennial problems (Plihal, et al., 1999). Scenarios, case studies, and role play provide learners with a real-life context for exploring concerns. With practice, learners enhance their capacity to utilize their reasoning skills as they navigate increasingly complex challenges (Smith, 1999).

Instructional Connections

Practical Problem-Based Curriculum

Authentic (practical) problems impacting families and communities and their interrelationships provide the foundation for setting curriculum priorities in an FCS classroom (Laster, 2001). When addressing a practical problem, individuals must integrate content knowledge from various disciplines and process skills to determine what action to take. The action selected is an ethical choice that requires analysis of the consequences to self and others, both long and short-term (Laster, 2001). Scenarios, role plays, and case studies provide a strategy for educators to develop learner thinking habits that explore questions of “what knowledge is of most worth” and “why” and “what ought to be” when exploring practical, “what should be” practical problems.

Moral Reasoning

The Practical Reasoning Framework is a process for determining which action, the judgment, should be taken to achieve the valued end when addressing a practical perennial problem (Olson, 1999). Determining the valued end of ‘what ought to be’ is a moral choice that considers if the judgment is good for all, the human condition, in contrast to good for an individual (Arcus, 1999). The moral reasoning process occurs as individuals ask questions about the context, identify alternatives, and examine the consequences of choices (Carpendale, 2000). The facilitation of scenarios, case studies, and role plays uses real-life opportunities to recognize that choices have positive and negative consequences and that a moral judgment may differ from an individual’s personal preference (Arcus, 1999). Furthermore, when assessing the implications and consequences of different actions, learners develop their question-asking skills to sort facts from options empathetically (Smith, 1999).

Language of Critique and Action

The mission of FCS guides practitioners to focus on enabling individuals to develop their potential to become autonomous participants in forming society while engaging in the language of critique to improve the living conditions for all (Brown & Paolucci, 1979). When examining a practical problem, learners develop their critical consciousness as they identify internal constraints (e.g., personal biases, lack of skill or point of view) and external constraints (e.g., abuse of power, exclusion, accessibility) to identify strategies and evaluate consequences of different actions (Rehm, 1999; McGregor, 2003). When determining what action to take, individuals must be able to engage in dialogue to develop understanding and recognize the influence of power when taking collective action (Rehm, 1999). When defining the problem, scenarios, case studies, and role plays challenge learners to recognize and reflect on personal assumptions to understand their values, attitudes, and beliefs as they support and explain what is occurring. While exploring what occurs in a collaborative environment, learners develop their perspective-taking and empathetic listening skills as they explore the strategies identified to address the challenge (Baumberger-Henry, 2005).

Critical Thinking Skills

Scenarios, case studies and role plays provide a provide learners with the opportunity to develop critical thinking skills through the eyes of the character (Smith, 1999). Critical thinking develops when learners are supported in developing the values of a critical thinker: autonomy, curiosity, humility, and respect for good reasoning when addressing a problem (Browne & Keeley, 2018, p. 10):

- Autonomy requires that individuals ask questions to understand widest possible array of possibilities, including among those who may have different value priorities.

- Curiosity requires that individuals actively listen and read to then ask questions about what was encountered to develop insights and understanding.

- Humility requires that individuals recognize that everyone is limited in what they know and believe to be fact while recognizing that everyone has different perspectives.

- Respect for good reasoning requires that individuals should respect and listen to all voices, conclusions and options while recognizing that not all solutions are equally worthwhile. Critical questions are necessary to identify the most reasoned action at the given time.

The Educational Environment

Create a Culture of Inquiry: Question Asking

A distinguishing characteristic of the critical science approach is how the “content develops in response to the questions asked” (Smith, 2004, p. 50). Emphasizing question-asking develops learners’ ability to think, reason, and reflect as they examine authentic situations in a scenario, role play, or case study. Educators and learners identify questions using each knowledge type from the Systems of Action Framework during the facilitation process. A learning environment driven by ongoing question-asking creates a dynamic atmosphere that challenges learners to think deeply while developing their reasoning abilities.

Create a Safe Space for Inquiry: Role of the Educator

As learners engage in inquiry learning processes that require critical thinking, reasoning, and perspective-taking to explore real-life human problems, the educational climate must be a safe space to explore behaviors and express feelings. The educator plays an essential role in creating this climate by letting learners know their ideas are respected because autonomy and humility are valued (Smith, 1999).

To facilitate environments that foster critical discourse among learners, educators need to be self-aware of who they are and their thinking patterns to model critical scrutiny of their biases, beliefs, and assumptions (Smith, 1999). An educator sets the tone in an educational environment by respectfully listening to what each learner is saying while asking probing and clarifying questions to encourage divergent points of view (Smith, 1999). Ultimately, learners must trust that the process of inquiry encourages personal growth.

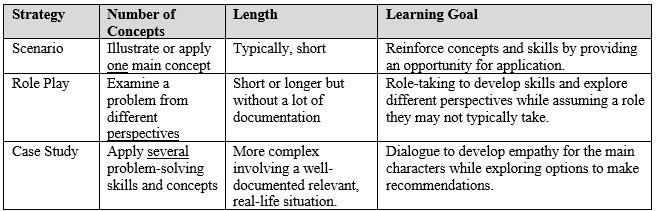

When to Use Each Strategy

Scenarios, case studies, and role plays are all forms of collaborative and active learning that help learners refine their understanding of a concept through practice, making choices, and receiving feedback. While the strategies are similar, understanding the fundamental differences assists an educator in creating a clear alignment between the strategy and the learning goal. The Center for Enhanced Teaching and Learning (CET&L) (n.d.) provides the following guidance:

Using Scenarios and Case Studies

Identifying and Developing Content

Meaningful scenarios and case studies require content relevant to the learners’ problems and personal dilemmas. Scenarios typically have well-defined content where they have an optimal solution, and only relevant information is provided (CET&L, n.d.). They are effective teaching strategies for developing and applying content knowledge and building foundational critical literacy skills. The content for case studies is often ill-structured to include relevant and irrelevant information as learners utilize higher-level critical thinking skills to devise a justifiable solution appropriate to the context (CET&L, n.d.).

There are numerous sources for identifying or developing content.

- Learners or educators: develop content reflective of the lived experiences of the learners or educators to provide an authentic and relevant foundation.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): utilize tools like ChatGPT to write a case study or scenario. When using AI, refine your message prompts with a clear topic/conflict, audience, and contextual factors.

- Short stories: A short story provides a meaningful opportunity to integrate literature into the learning environment with a reader-friendly text as the length is limited to 50-30,000 words with a single plot and a limited number of characters.

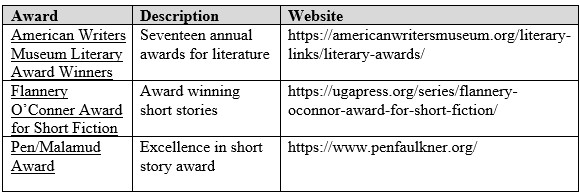

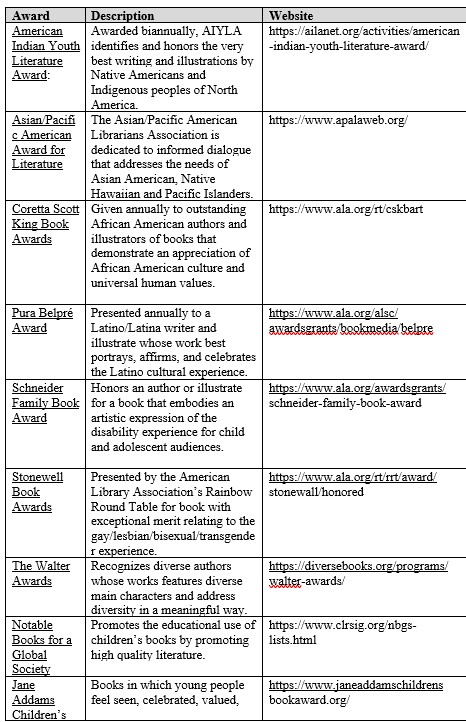

- Children and Young Adult Literature: Botelho and Rudman (2009) discuss why all learners need to see themselves reflected in the literature they read (mirrors), how books can introduce learners to other cultures and ways of life (windows), and that reading can result in new understanding and appreciation of diversity (doors). Integrating children and young adult literature into the learning environment creates case studies that build empathy, understanding, and compassion in learners. Consider integrating literature as case studies from a variety of award-winning authors:

![]()

- Visual Case Studies: Visual media, like TV or movies, in an educational environment can be conceptualized as visual case studies that provide the “needed link between theory and reality” (Macy & Terry, 2008, p. 33). Educators may use an entire movie, a television series or single episodes and small clips to analyze the portrayal of realistic life events while simultaneously developing media literacy skills.

Planning and Conducting a Scenario or Case Study

Scenarios allow learners to apply what they are learning to real-life situations, issues, and decision-making. When using content knowledge, learners develop their critical thinking and problem-solving skills while exploring the transferability of content learned to different situations.

Because scenarios are short and focused, they work well for introducing a lesson, providing formative assessment check-in points during a lesson, or as a summative assessment as a worksheet or test question at the end of a lesson. When facilitating a scenario:

- Introduce: Introduce the scenario by defining the content focus, often framed using a real-world inquiry question. Identify the task the learners will complete (e.g., solve a problem, identify alternatives, choose the best option) and how knowledge will be demonstrated (e.g., written justification, completion of a graphic organizer)

- Apply: Have learners work individually or in small groups to examine the scenario and complete the learning task.

- Reflect: Instruct the group to share their analysis of the scenario. Ask reflection questions that encourage learners to examine both the content and the learning process.

Case studies also illustrate a real-life situation. However, the problem is often more complex, requiring several problem-solving skills and concepts to identify possible outcomes and solutions. Because of their complexity, case studies effectively develop reasoning skills in learners to consider multiple perspectives, alternatives, and the moral and ethical consequences of the potential actions.

A case study works well to support the facilitation of a lesson or as a summative assessment. When facilitating a case study:

- Introduce: Introduce the case study by describing the practical problem that learners will explore. After learners have read the case study, prompt critical thinking by asking open-ended questions that help them recognize the complexity of the case study. For example:

- What is the real problem (technical)?

- Do we have all the information we need (technical)?

- What viewpoints and beliefs do those affected have (communicative)?

- What social forces brought this about (communicative)?

- Apply: Have learners work individually or in small groups to examine the case study to complete the defined task (solve a problem, identify alternatives, make a recommendation). Enhance critical thinking and perspective-taking by:

-

- Graphic organizer:providing learners with tools to support thinking such as a perspective analysis, cause/effect graphic organizer, Practical Reasoning think sheet, etc.

- Question asking:pause learners throughout the case study analysis to encourage them to ask clarifying questions, compare and contrast their analysis with other learners, or respond to questions asked by the educator that enable them to analyze the potential consequences of different actions.

- Reflect:Instruct the group to share their analysis of the case study. Encourage self-reflection about the process of addressing complex problems.

Case Study and Scenarios: Variations and Extensions

- Cooperative Learning:Use cooperative small-group discussion strategies to support learners in building their communication skills. For example:

- Socratic Seminar:Facilitate the seminar or case study analysis using the Socratic Seminar learner-led discussion method. A Socratic seminar emphasizes inquiry through questions asking to explore and evaluate the ideas, issues, and values in the text of a case study or scenario through a group discussion. For detailed instructions, visit Facing History (facinghistory.org).

- Multiple perspectives: Encourage perspective-taking and empathy by highlighting the values and needs of those impacted by the problem by using various approaches.

- Roles:assign learners to different roles where they analyze the scenario or case study from a specific perspective.

- Alternatives:require learners to identify multiple solutions to a complex problem by analyzing different interpretations of the dilemma.

- Multiple contexts: Provide each learner or small group with a different family scenario to explore how the problem setting (values and contextual factors) influences why other solutions may be best for the family when addressing the same complex problem.

- Increased Complexity: Utilize the same case study through a course or unit but increase the case’s complexity by providing ‘evolving situations’ that require learners to revisit previous recommendations based on new information learned, changes in contextual factors, etc.

Scenario and Case Study Examples

Child Development: Learners with Diverse Support Needs

FCS Objective: 12.1 Analyze conditions that influence human growth and development.

Inquiry Question: How can we create more inclusive experiences and environments for individuals with diverse support needs?

Source: Children’s books

- Unbound: The Life + Art of Judith Scottby Joyce Scott, Brie Spangler, and Melissa Sweet (a true story about Judith Scott, who was born with Down syndrome and was deaf and unable to speak)

- Awesomely Emma: A Charley and Emma Story by Amy Web and Merrilee Liddiard (a story about Emma who has limb differences and uses a wheelchair)

- Walking Through the World of Aromas by Ariel Andres Almada and Sonja Wimmer (a story about Annie who was born without sight and uses her sense of smell to become an excellent cook)

Facilitation:

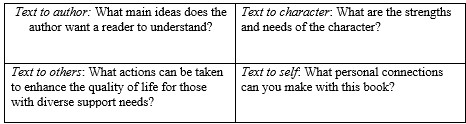

- Break learners into small groups, each with a different story. As they read the story, have them complete a Window Notes graphic organizer to answer four questions as they reflect.

- Have groups present their Window Notes to the class. During the discussion, have learners identify similarities and differences between the experiences and core messages in each book.

Relationships: Qualities of A Good Friend

FCS Objective: 13.2 Analyze functions and expectations of various types of relationships.

Inquiry Question: What are the characteristics of a good friend?

Sources: Use one or more movie clips, including:

- Movie: Ron’s Gone Wrong – Clip: “How To Be a Friend”

- Movie: Toy Story – Clip: “You’ve Got a Friend in Me”

- Movie: Up – Clip: “Making Friends”

Facilitation: While the clips are shown, have learners create a concept map illustrating qualities conveyed by the characters reflective of being a good friend. Encourage self-reflection through a large group and small group discussion using prompts from each system of action level, such as:

- What friendship qualities are important to you (communicative)?

- Where in your upbringing did you develop those beliefs (communicative)?

- What actions did the characters take to demonstrate their qualities (communicative)?

- What would happen if everyone chose actions reflective of quality friendship (reflective)?

Work-Family Integration: Roles

FCS Objective: 6.2 Evaluate the effects of diverse perspectives, needs, and characteristics of individuals and families.

Inquiry Question: How do perspectives about roles influence communication and decision-making processes within a family?

Source: ChatGPT (2024)

- Case Study #1: The Modern Dilemma

- Adrian and Elliott are a married couple in their early thirties, both pursing successful careers. They share household responsibilities and childcare equally. Adrian is a software engineer, and Elliott is a high school teacher. They have a two-year-old daughter, Emma. Adrian is offered a promotion that would require longer work hours and taking on more responsibilities. Elliott supports Adrian’s career ambitions but is concerned about the potential impact on their family life. They both value equality in their relationship but are now facing the dilemma of how to balance career aspirations with family responsibilities.

- Case Study #2: Cultural Expectations

- Mia and Gabriel are a couple in their late twenties, recently immigrated to the United States from a traditional society. Mia grew up in a culture where gender roles were strictly defined, with clear expectations for women’s roles in the household. Gabriel, on the other hand, was exposed to more progressive ideas about gender roles during his education abroad. As they adjust to life in the U.S., Mia feels conflicted about deviating from the traditional gender roles she grew up with, while Gabriel encourages a more egalitarian approach. They are expecting their first child, and the question of parenting responsibilities become a point of discussion between them.

Facilitation:

- Break the learners into small groups of 2-4 and give half of the groups case study #1 and the other half of the groups case study #2.

- Provide the groups with discussion questions to encourage them to examine the multitude of contextual factors that influence the perspectives of everyone in their case study. For example:

- What are our alternatives (technical)?

- Where could such a belief originate (communicative)?

- What are they trying to make happen (communicative)?

- What values support the decision (reflective)?

- Have each group present a synthesis of their discussion to the whole class. During the presentations, create a visual mind map on the wall with ‘roles’ at the center to identify similarities and differences among the different factors that influence role perspectives within families.

The Role Play Strategy

The role-play strategy allows learners to explore how values drive behavior when individuals seek resolution and understanding while addressing a human-relations problem (Joyce et al., 2015). When developing critical thinking through role-play, learners enhance their abilities to deal with the unpredictable nature of oral communication while interacting with persons with different values, attitudes, and beliefs (Smith, 1999). This skill-based practice can also help learners develop strategies for resolving conflict and solving problems (Joyce et al., 2015). Furthermore, role plays can help to develop confidence in navigating unfamiliar or uncomfortable situations (Smith, 1999).

Planning & Conducting a Role Play:

When conducting a role play focused on social values and decision-making, Fannie and George Shaftel (1967) developed a nine-step process to enhance the richness and focus of the learning activity while creating a syntax that honors the complexity of problem-solving (Joyce et al., 2015). The phases include (1) warm up the group (2) select participants (3) set the stage (4) prepare the observers (5) enact (6) discuss and evaluate (7) reenact (8) discuss and evaluate and (9) share experiences and generalize.

1: Warm Up the Group

This phase is foundational to the success of the role play as learners must feel that the problem presented is relevant to their lives, and the role-play environment is one of acceptance where learners believe that they can explore all views, feelings, and behaviors (Joyce et al., 2015). As the educator creates awareness among learners about the problem, they ask questions at each System of Action level to begin interpreting the problems and exploring the resulting consequences.

2: Select Participants

The roles of the different characters are explored by brainstorming what they are like, how they feel, and how their values may influence what they might do (Joyce et al., 2015). The learners should volunteer for the position to avoid bias by placing people in different roles (Shaftel, 1982). When identifying individuals for roles, educators can and should inform the process by selecting learners who will provide an authentic interpretation of the problem by having comfort with the identity of the role or may benefit from exploring varying perspectives (Joyce et al., 2015).

3: Set the Stage

Provide each role player with time to clarify their role further by outlining a simple line of action to explore within the context of the problem setting (Joyce et al., 2015). Discussion from phase one and the role players’ personal experiences help to set the stage rather than providing a written script.

4: Prepare the Observers

Set the tone for active engagement among all learners by defining the responsibilities of those observing the role play (Joyce et al., 2015). Options include assigning everyone a task to examine the dilemma from a different perspective (varying roles, values, knowledge) or asking learners to analyze the effectiveness of the sequence of actions.

5: Enact, 6: Discuss and Evaluate, 7: Re-enact, 8: Discuss and Evaluate

Phases five through eight are a repeated sequence of short enactments that conclude after a behavior is demonstrated, a core viewpoint is expressed, or when progress is no longer occurring (Joyce et al., 2015). After each enactment, the facilitator pauses the group to discuss and evaluate what was observed.

Phase 5, the first enactment, introduces the role of each actor and the core problem. In phase six, learners discuss and evaluate what occurred, emphasizing exploring interpretations of the problem, factors influencing decision-making, and the consequences of actions (Joyce et al., 2015). Then, in phases seven and eight, the learners reenact the role play, emphasizing how problem outcomes may be different based on everyone’s values, the problem context, and the different choices and consequences of each action. Phases seven and eight may be repeated as many as necessary to illustrate the complex and real-life factors influencing the problem-solving processes.

9: Share Experiences and Generalize

Learning is transferred from the role play to real life by engaging the learners in dialogue to connect the role play to real-life experiences. From this connection point, learners are prompted to reflect on what was learned from the role play that can be applied to their life. Examples of connections may be a how-to process (such as active listening), use of questioning to gain clarify and gain insight about a problem, analysis of the consequence of choices to a similar dilemma in their setting.

Role Play: Variations and Extensions

Practical Reasoning Process: Structure each role play enactment to explore a distinct element of the Practical Reasoning Process. Provide learners with a Practical Reasoning Framework Think Sheet to support their reflection.

Small Groups: Have learners work in small groups to complete the role play. When determining group size, have learners who are conducting the role play as well as leaners who are observers to help facilitate the debriefing.

Role Play Examples

Role Play: Family Mealtime

Practical Perennial Problem: What should be done about cost, time, and other resources to support family mealtime?

FCS National Standard: 2.1: Demonstrate management of individual and family resources such as food, clothing, shelter, health care, recreation, transportation, time, and human capital.

Facilitation Structure: Small groups using Practical Reasoning

1: Warm up the Group

Begin exploring family mealtime:

- Create definitions of what core terms (e.g., quality time, family, family mealtime) mean to them individually and collectively (communicative);

- Brainstorm and critically examine factors that influence why a dedicated family mealtime may or may not occur within a family (reflective);

- Identify the benefits of family mealtime by evaluating articles about the benefits of family mealtime and strategies to address barriers (communicative; technical).

2: Select Participants

Small Groups:

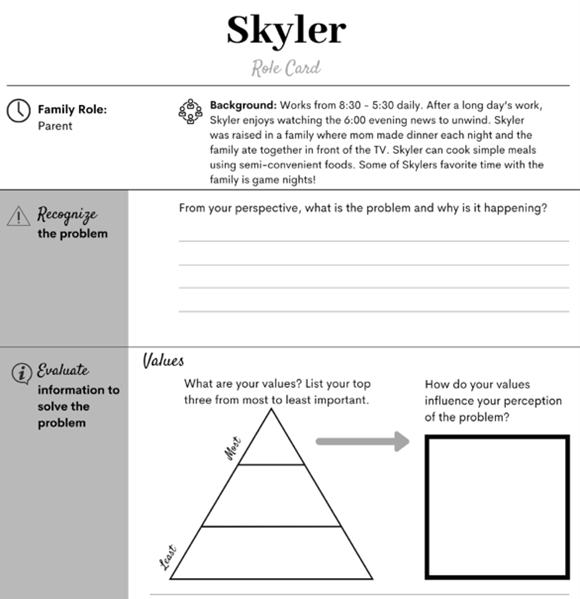

- Break participants into small groups with four family members and 1-2 facilitators per group. Have participants choose their preferred role (parent, child, or facilitator).

Role Cards:

- Give each person assuming the role of a family member a role card with background information about their perspectives and Practical Reasoning Think sheet prompts to guide them through the process.

3: Set the Stage

Scenario: they are members of the Darby family, with two full-time working parents and two adolescent children actively involved in after-school activities. The family has realized they have started eating out a lot, impacting their budget. Furthermore, the family values meaningful connection. They used to eat dinner together several times a week, but now they are happy to eat together monthly. Consequently, family communication has become strained. A family meeting has been called to explore options for reallocating their resources to establish some form of family mealtime.

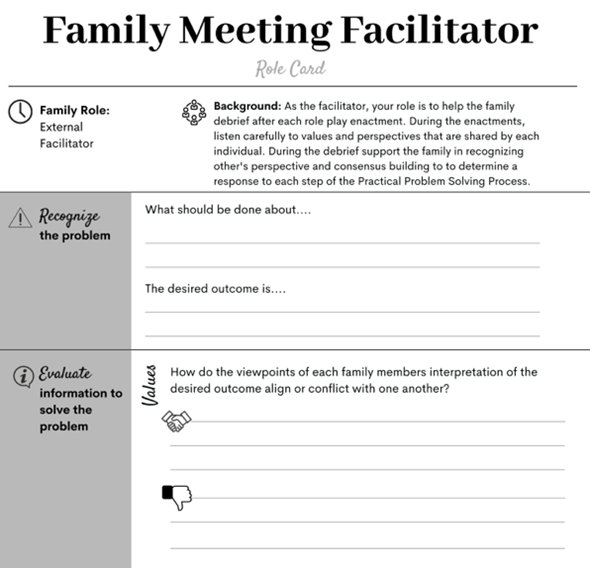

4: Prepare the Observers

Provide the facilitator with a role card with questions to help the ‘family’ reflect after each enrollment.

5-8: Enact, Discuss and Evaluate (repeated)

Conduct several rounds of the role play, each focusing on a different aspect of the Practical Reasoning Think Sheet. Each round is sequenced as follows:

- Before: Give each role-play participant time to use the worksheet to reflect on their perspective of the Practical Reasoning element.

- During: Conduct the role play for 2-5 minutes, discussing the specific Practical Reasoning element.

- After: Facilitators will guide the family in a debriefing using System of Action prompts.

| Round 1: The Problem | What is the problem and why it is happening from each person’s perspective. |

| Round 2: Values | How do values influence perceptions of the problem and the valued end?

|

| Round 3: Resources | What resources are available or needed to address the problem?

|

| Round 4: Criteria | What criteria are important to each family member when solving the problem?

|

| Round 5: Solutions | What are at least two potential solutions for addressing the problem?

|

| Round 6: Consequences and Decision | What are the consequences of each potential solution? What option is best?

|

| Round 7: Create a Plan to Take Action | What is our family plan for achieving the solution?

|

9: Share Experiences & Generalize

Have small groups share their decision with a justification of ‘why’ it is the best choice for the family. Compare and contrast the different solutions each group identified despite a similar scenario. Participants reflected on the impact of the Practical Reasoning process on their thinking as they navigated the problem individually and within a family.

Role Play: Rental Woes: Landlord Tenant Dilemma

Practical Perennial Problem: What should I do when relating in positive and caring ways during conflict?

FCS National Standard: 2.3: Analyze policies that support consumer rights and responsibilities.

Facilitation Structure: Role play with large group

1: Warm up the Group

Begin exploring common landlord-tenant dilemmas:

- Explore the responsibilities of the tenant and the landlord by creating a list of five responsibilities of each with a rationale of why (communicative);

- Brainstorm and critically examine common dilemmas and factors that influence the cause of landlord and tenant dilemmas (reflective);

- Read a rental lease contract and compare the contract terms to the list of responsibilities (communicative; technical).

2: Select Participants

Ask for two volunteers and provide them with role cards indicating their responsibilities and personality traits:

Landlord

- Responsibilities: Owns the rental property, collects rent, manages maintenance and repairs, and ensures compliance with lease terms.

- Personality traits: Business-minded, concerned about property upkeep, and may have financial pressures.

Tenant

- Responsibilities: Rents the property, pays rent on time, maintains the property in good condition, and complies with the lease terms.

- Personality traits: resourceful, may face financial constraints, values privacy and comfort.

3: Set the Stage

Scenario: The landlord wants to increase rent due to the rising property taxes and maintenance costs. However, the tenant is struggling financially and cannot afford the higher rent. The tenant believes the increase is unfair and requests additional time to find a solution. The landlord is adamant about increasing rent to cover expenses and maintain profitability. The conflict escalates as both parties stand their ground.

Extension: Conduct the role-play several times using various scenarios identified in stage 1.

4: Prepare the Observers

Perspective-taking focus: Assign half of the observers to the landlord and half to the tenant. Their task is to examine how the perspective of each person is influencing how and what they are communicating.

5-8: Enact, Discuss and Evaluate (repeated)

Conduct several short rounds of the role play, each focusing on a different aspect of the dilemma. Before each round, provide the role players with guidance about the purpose of the round and give them time to prepare. After each round, debrief.

| Round 1: The Problem | What is the problem, and why is it happening from each person’s perspective?

After the round, discuss:

|

| Round 2: The Contract | What are the rights and responsibilities of each person?

|

| Round 3: The Resolution | What are the options, consequences of each option, and best solution?

|

References

Arcus, M. E., (1999). Moral reasoning. In J. Johnson & C.G., Fedje (Eds.), Family and Consumer Sciences Curriculum: Toward a Critical Science Approach – Yearbook 19 (pp. 174-183). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Baumberger-Hentry, M. (2005). Cooperative learning and case study: Does the combination improve students’ perception of problem-solving and decision making skills? Nurse Education Today, 25(3), 238-246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2005.01.010

Browne, M. N. & Kelley, S.M. (2018). Asking the right questions: A guide to critical thinking (12th ed.). Pearson.

Brown, M. M., & Paolucci, B. (1979). Home economics: A definition. American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences

Botelho, M. J. & Rudman, M. K. (2009). Critical multicultural analysis of children’s literature: Mirrors, windows and doors. Routledge.

Carpendale, J. (2000). Kohlberg and Piaget on stages of moral reasoning. Developmental Review, 20(2), 181-205. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.1999.0500

Centre for Enhanced Teaching & Learning (CET&L) (n.d.). Creating effective scenarios, case studies and role plays. University of New Brunswick. https://www.unb.ca/fredericton/cetl/services/teaching-tips/instructional-methods/creating-effective-scenarios,-case-studies-and-role-plays.html

Joyce, B., Weil, M., & Calhoun, E. (2015). Models of teaching (9th ed.). Pearson.

Laster, J. F. (2001). Principles of teaching practice in family and consumer sciences education. In J.F. Laster & J. Johnson (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences: A chapter of the curriculum handbook (revised and updated., pp. 63-86). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Macy, A., & Terry, N. (2008). Using movies as a vehicle for critical thinking in economics and

business. Journal of Economics and Economic Education Research, 9, 31–54.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2003). Critical science approach – A primer. Kappa Omicron Nu FORUM, 15(1). https://publications.kon.org/archives/forum/forum15-1.html

Olson, K. (1999). Practical reasoning. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 132-143). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

OpenAI. (2024). ChatGPT (3.5) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com

Plihal, J., Laird, M., & Rehm, M. (1999). The meaning of curriculum: Alternative perspectives. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 2-22). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Rehm, M. (1999). Learning a new language. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 58-69). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Selbin, S. (1999). Developing questions in critical science. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 167-173). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Shaftel, G. (1982). Role playing in the curriculum (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall.

Smith, F. M. (1999). Practicing critical thinking through role play. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 184-194). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Smith, B. P. (2004). FCS curriculum development and the critical science perspective. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 96(1), 49-51.

Vincenti, V. B. (2002). Addressing problems effectively using critical science. American Home Economics Association.