6 Meaning Making: Conceptual Thinking Strategies

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to:

- Define a concept and distinguish it from a fact, articulating the essential attributes of a concept and recognizing how interpretations may vary among individuals.

- Analyze broad concepts such as family, culture, and communication to identify their characteristics and understand their interconnectedness within real-life contexts.

- Engage in conceptual thinking strategies, such as comparing and contrasting or concept mapping, to synthesize and evaluate the attributes of a concept, strengthening their ability to transfer learning across various contexts.

- Evaluate how socio-historical experiences shape individual and collective meanings of abstract concepts, enhancing their ability to reason within the communication process and tolerate ambiguity.

- Apply conceptual thinking strategies to examine practical perennial problems, identifying complex factors and proposing informed solutions through systematic reasoning.

- Develop and use conceptual questions to guide inquiry and deepen their understanding of abstract and concrete concepts, emphasizing perspective-taking and the values inherent in each viewpoint.

- Work collaboratively to refine your understanding of concepts, sharing insights and using tools such as concept maps and graphic organizers to visualize relationships and enhance group learning outcomes.

Merriam-Webster dictionary (n.d.) defines a concept as an abstract thought or idea. Concepts include a set of characteristics that individuals assign meaning to and organize in their minds to make sense of information. When analyzing components of a concept, learners are actively involved in observing, comparing, and finding similarities and differences, allowing for the formation of new insights (Carlson & Johnson, 1999). By engaging in higher-level conceptual thinking, learners develop their ability to think critically and systematically about the different components of a concept or situation to understand the whole and transfer the concept to new sources (Stobaugh, 2019).

A concept is different from a fact. Facts are pieces of information and technical knowledge. The meaning of a concept may be interpreted differently by individuals. For example, individuals have varying definitions of terms such as family or responsibility. When recognizing multiple meanings associated with a concept while articulating its essential attributes, learners develop their communicative/interpretive knowledge as they develop their conceptual clarity beyond assigning a label (Stobaugh, 2019). Analyzing the meaning of concepts also strengthens a learner’s ability to communicate with others to seek shared meaning (Carlson & Johnson, 1999).

Practical Reasoning (Critical Science) Approach: Instructional Connections

Practical Perennial Problem

Practical perennial problems that impact the human condition inform the content of a course designed with a critical science approach. When practical problems are formed as a “what should be done about” question, an FCS curriculum has an inquiry approach where learners are co-investigators with the educator to examine the concern (Montgomery, 2008). Conceptual thinking supports a learner’s ability to recognize complex factors contributing to a practical problem across multiple systems as well as the different ways in which individuals may interpret the meaning of a concern.

Broad Concepts

Broad concepts form the foundation of a FCS curriculum that leads to enduring understandings (Montgomery, 2008). Broad concepts are like big ideas within the Understanding by Design Framework, fundamental concepts that require analysis because the meaning often needs to be clarified or is counterintuitive (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). In a curriculum that focuses on broad concepts, learners engage in hands-on activities to develop technical skills as a means to an end to foster an understanding of broad concepts that are recurring concerns of the family such as culture, communication, and family (Fedje, 1999). When understanding develops, a curriculum is more integrated, allowing the learner to make connections between sub-concepts and their knowledge of various real-life settings (Montgomery, 2008).

Communicative/Interpretative System of Action

This system of action focuses on the meanings individuals associate with concepts shaped by their socio-historical experiences (e.g., family culture and traditions, social norms) that guide thinking patterns and beliefs (Montgomery, 2008). Awareness of the meaning associated with abstract concepts such as family or happiness helps learners understand the perspectives that inform language, social values, and norms. In addition, a learner’s sensitivity to reasoning within the communication process and tolerance of ambiguity is enhanced (Carlson & Johnson, 1999).

Critical Thinking Skills

Learners who engage in conceptual thinking strategies build their critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Furthermore, the strategies address some of the barriers to teaching critical thinking including a focus on information recall types of worksheets or assessment tools that emphasize one correct response and feeling the need to address all content rather than the broader concepts (Swafford & Rafferty, 2016). When thinking conceptually, learners:

- Synthesize: Work in small groups to explore perspectives and share insights while developing language to describe a concept.

- Analyze: Differentiate elements of a concept and examine the relationships between the elements.

- Evaluate: Critique numerous examples to determine characteristics of a concept, which helps to develop an individual’s ability to weigh options when problem-solving.

The Educational Environment

Creating a Culture of Inquiry: Question Asking

Using question-asking to guide content knowledge development is essential to an inquiry-focused pedagogy that addresses practical problems (Holcombe & Fedje, 1983). Essential to the effectiveness of conceptual thinking strategies is the use of questioning by the educator and learners to analyze the meaning of a concept. As educators prepare to conduct any conceptual thinking strategy, they must complete the concept analysis first to refine their development of artifacts/clues and questions that can be asked throughout instruction to support learners in thinking critically about the concept (Johnson et al., 1992).

Classrooms with a culture of inquiry that focuses on question-asking and exploration develop reasoning abilities. Conceptual questions emphasize perspective-taking abilities as learners develop a deep understanding of an abstract or broad concept while becoming aware of the inherent values that shape each perspective (Laster & Johnson, 2001). Examples of conceptual questions include (Laster & Johnson, 2001, p. 6):

- What is the meaning of the concept we are studying?

- How did we come to the unquestioned assumption?

- How is that meaning different from the meaning held by….?

- What personal factors are involved (e.g., economics, gender, race)?

Within Family and Consumer Sciences, a concept may be more concrete with readily available answers such as an interest rate, developmental stage, or nutrient. When examining concrete concepts, learning extends beyond defining a term to understanding the factors influencing the cause/effect or means/end of the term. A deeper understanding of terminology enhances comprehension and transferability of the term to multiple contexts (Anders & Guzzetti, 2005). Examples of conceptual questions include (Laster & Johnson, 2001, p. 6):

- What causes the problem to occur?

- What are the consequences or effects?

- What steps should be taken?

Create a Safe Space for Inquiry: Role of the Educator

Educators with a critical science orientation facilitate environments that integrate the accumulation of facts and skills with critical thinking and reasoning skills to encourage self-autonomy development. When facilitating discussions and designing assessment tools, educators move away from a focus on the ‘right’ answer (Fedje, 1999). Instead, educators use questions at each system of action level to guide the content as learners develop their self-autonomy and become critical thinkers aware of the multiple meanings of many concepts.

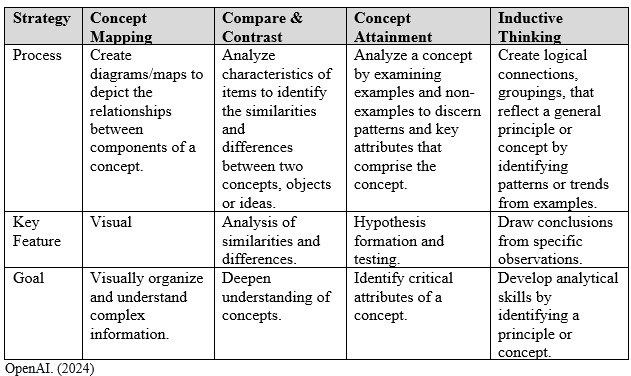

Conceptual Thinking Strategies and When to Use

The ability to analyze abstract concepts is a critical thinking skill learners develop with practice. This chapter highlights four evidence-driven strategies that foster higher-level conceptual thinking.

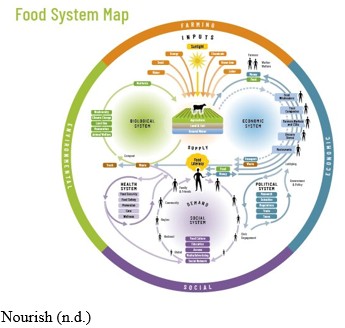

Concept Mapping

Concept Mapping is a practical strategy in which learners visually represent a concept to illustrate relationships among ideas (Stobaugh, 2019). When creating a concept map, learners engage in metacognitive thinking while reflecting on their underlying assumptions about the concept (Carlson & Johnson, 1999). Within Family and Consumer Sciences, concept mapping effectively supports learners in recognizing the complexity of practical problems and the need for multidisciplinary thinking.

There are distinct differences in the thinking processes required between concept mapping and similar strategies such as graphic organizers and mind maps. When creating a concept map, the educators identify the central idea (concept), and the learner determines how to systematically organize information to illustrate the multitude of relationships between ideas and visual layers. In contrast, when using a graphic organizer, the educator has already determined the relationships by providing a visual diagram that learners complete. A mind map differs from a concept map in that a mind map begins with a single idea at the center, with one later of related ideas radiating from the center. The design of a mind map is always radial, like a tire. In contrast, a concept map is a flexible series of connected parts to illustrate the cross-link relationships among the ideas (Eppler, 2006). When illustrating the layers of relationships of an abstract concept or practical problem, conceptual mapping is a strategy for focusing on the big picture while generating higher levels of conceptual understanding (Eppler, 2006).

Concept Mapping: Planning and Conducting

Concept Mapping is a versatile strategy that may be used at multiple points in an instructional plan.

- Pre and formative assessment: Use at the beginning of instruction to identify what learners understand about a concept or a practical perennial problem. Then, after learning, revise their concept map to reflect new associations between ideas and add missing information.

- During learning: After sharing an informational text or video with learners, ask them to create a concept map synthesizing the main idea with supporting details.

- Formative assessment: Use concept mapping to check for understanding after studying a topic.

To facilitate the concept mapping strategy:

- Determine what tool learners will use to create their diagram. This may be paper or pencil, on a whiteboard, or digitally using tools such as Microsoft SmartArt, Miro, Canva, etc.

- Share the central idea that will be the focus of the concept map.

- Give learners approximately 5 minutes to brainstorm everything they know about the central idea.

- Challenge learners to brainstorm to identify associated concepts supporting the central idea. Based on the central idea’s complexity, the educator may choose to give learners a specific number of associated ideas to identify.

- Encourage learners to organize their brainstorming in a way that best illustrates the relationships between ideas.

Concept Mapping: Variations and Extensions

Scaffold Skill Development: Guide learners in their ability to identify organizational structure of text by indicating what type of thinking pattern (e.g., compare and contrast, cause and effect, problem/solution, timeline) aids in analyzing the concept. Support learners by providing them with the sub-concepts categories to inform their brainstorming.

Cooperation: After learners have individually created their concept map, create small groups to have them present their concept map to their peers while sharing their rationale for their topics and organizational structure. Encourage groups to compare similarities and differences in their concept map. After sharing, provide learners with time to individually refine their concept map.

Reflection: Challenge learners to reflect on their mind map by completing a quick write to relate the core characteristics of the concept to a real-life example.

Concept Mapping: Example

Topic/Criteria: Food Security

National FCS Standard: 14.5 Evaluate the influence of science and technology on food, nutrition, and wellness.

Practical Perennial Problem: What should be done to enhance food literacy?

Compare and Contrast

The Compare and Contrast strategy encourages learners to think deeply about two or three concepts by comparing characteristics that may be more abstract, easy to overlook, or confuse with other concepts (Silver et al., 2007). By engaging in comparative thinking to identify the similarities and differences between two items, learners gain a deeper understanding of each concept individually and how the concepts relate. When analyzing the items, learners engage in higher-order thinking that increases memory retention and transferability of knowledge to other contexts (Silver et al., 2007).

Compare and Contrast: Planning and Conducting

The compare and contrast strategy is used during instructional content facilitation as learners critically analyze characteristics of pre-identified concepts to articulate similarities and differences.

To facilitate the compare and contrast strategy:

- Identify the purpose of comparing. What should learners know or be able to do upon thinking critically about characteristics that distinguish the similarities and differences between two items?

- Choose two separate items (e.g., objects, concepts, images, text) for the comparison.

- Describe to learners:

- The purpose of why they are comparing two items.

- Criteria for how they will be comparing the items.

- If applicable, provide the definition of each item.

- Have learners use the criteria to research and describe the characteristics of each item separately. Identify information sources (e.g., books, videos, websites) for their research.

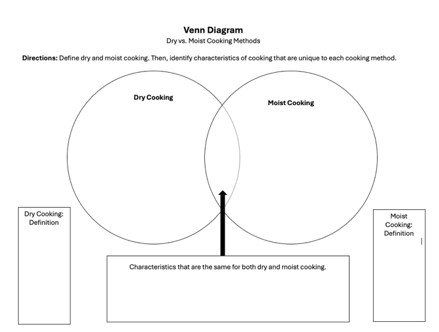

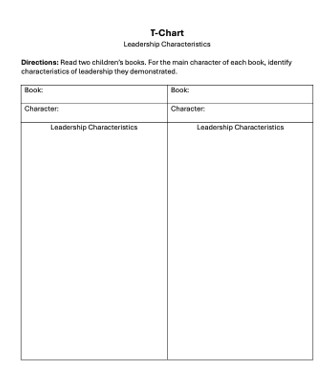

- Provide learners with a comparison graphic organizer to distinguish how the characteristics of each item are similar and different. Examples of comparison graphic organizers include:

- Venn Diagram

- T-chart

- Alike but Different (also known as compare and contrast)

- Facilitate a discussion with learners to draw conclusions about the relationship between the items from analyzing their graphic organizer. Discussion questions may include:

- How are these items alike?

- What is the most crucial difference? How will you remember?

- What conclusions can you draw about why these items are different?

- What real-life examples can you provide to distinguish these items further?

Compare and Contrast: Variations and Extensions

Increase Complexity: Compare and contrast among three items. To scaffold learning, conduct the process with two items and then repeat, adding a third item and a three-part graphic organizer.

Perspective Taking:

- Identify a practical problem that learners will compare.

- For the criteria, utilize contrasting perspectives (e.g., values, content knowledge, alternatives) to address the problem.

- When facilitating the discussion, emphasize that despite the differences, there are also similarities among perspectives when exploring solutions to social problems.

Cooperative Learning: Integrate the Jigsaw strategy into the facilitation (learn more about Jigsaw from AdLit.org: https://www.adlit.org/in-the-classroom/strategies/jigsaw). Divide the learners into two groups. Assign each group to become an expert for one of the items during the research phase. Then, create new groups that mix an expert from each item to teach their peer about their topic while cooperatively completing the graphic organizer to distinguish the similarities and differences.

Customize Graphic Organizers: When providing graphic organizers, customize the directions and prompts to be specific to the instructional content and facilitation method to enhance clarity in how the graphic organizer may support thinking.

Compare and Contrast: Examples

Topic/Criteria: Dry Cooking Methods versus Moist Cooking Methods

National FCS Standard: 8.5 – Demonstrate professional food preparation methods and techniques for all menu categories to produce a variety of food products that meet consumer’s needs.

Learning Material: Textbook or Website

Graphic Organizer: Venn Diagram (download at www.readwritethink.org)

Facilitation: After defining two fundamental cooking methods, dry and moist cooking, have learners use a textbook for research. Comparison points may include type of heat transfer, impact on texture and flavor, and examples of foods cooked using each method. After learners have completed their graphic organizer, have them work in small groups or as a large class to compare and contrast insights and make any refinements needed to their organizer.

Topic/Criteria: Characteristics of Leadership

National FCS Standard: 13.5 – Demonstrate teamwork and leadership skills in the family, workplace, and community.

Learning Materials: Children’s Books – examples include:

- Sophia Valdez, Future Prez by Andrea Beaty

- So Tall Within: Sojourner Truth’s Long Walk Toward Freedom by Gary D. Schmidt

- Dear Mr. President by Sophie Siers

- What’s My Superpower by Aviaq Johnston

- Our Future: How Kids are Taking Action by Janet Wilson

Graphic Organizer: T-Chart (download at www.readwritethink.org)

Facilitation: As a large group, create a definition of leadership. Then, explore the characteristics of leaders by integrating the Jigsaw Cooperative Learning strategy. Break learners into small groups and provide each group with one story to read and analyze to identify characteristics of leadership demonstrated by the book’s characters. Then, create mixed groups where each person has read a different story. Have learners synthesize their story and leadership characteristics identified to compare and contrast similarities and differences. Encourage small groups to think critically about contextual factors in each story that may have influenced the development of leadership traits. Bring the large group together to create a master list of leadership characteristics across the different texts and refine their definition of leadership.

Topic/Criteria: Depository Institution Accounts – Checking vs. Savings

National FCS Standard: 3.3 Analyze factors in guiding the development of long-term financial management plans.

Learning Material: Local Depository Institution Websites or Lecture

Graphic Organizer: Alike but Different (also known as compare and contrast, download at www.readwritethink.org)

Facilitation: After a lecture about checking and savings accounts at depository institutions, have learners reference their notes and engage in higher order thinking by completing the Alike but Different graphic organizer to compare and contrast similarities and differences in the types of accounts. Extend learning by encouraging learners to integrate references into their graphic organizer by exploring local depository institution websites. As a formative assessment, encourage learners to create a mnemonic, draw a picture, or write a short statement about how they will remember the essential differences between the two account types.

Concept Attainment

The Concept Attainment strategy evolved from Jerome Bruner’s 1973 work, which identified how humans naturally group information into categories from an early age to cope with diverse environments (Joyce et al., 2015). Concept Attainment supports learners in exploring a concept actively and deeply by analyzing examples to determine if the attributes of each example are characteristic of the concept. By distinguishing among various examples to identify patterns and critical attributes, learners develop an in-depth understanding of a concept that allows them to apply it to new situations or problems accurately.

While similar, the concept attainment and compare and contrast strategies have differences in their primary purpose and process. The compare and contrast strategy emphasizes relationships between two concepts when identifying their similarities and differences. In contrast, the concept attainment strategy emphasizes defining the key attributes of one concept through the analysis of examples and non-examples. The concept attainment learning process builds knowledge inductively, from the ground up, as learners use examples to form and test hypotheses to develop an understanding of a concept (Joyce et al., 2015).

Concept Attainment: Planning and Conducting

Johnson et al. (1992) and Joyce et al. (2015) provide the following guidance when facilitating the concept attainment strategy:

- Identify the core concept for learners to understand or analyze. At the understanding level of Bloom’s Taxonomy, attributes of the idea are clearly defined, such as foods that are high in vitamin A. At the analyze level of Bloom’s Taxonomy, the concept is more abstract, such as cooperation.

- Determine what key attributes represent the concept.

- Tip: Create a concept map to identify critical attributes when preparing instruction.

- Determine what clues reflect the concept by creating a list of positive (yes) examples that contain the attributes and non-examples (no) that contain some or none of the concept’s attributes. Examples of clues may be from various text forms, including pictures, movie clips, words, objects, songs, etc.

- Determine if you will share the examples individually or in groups of two.

- Single examples: Share one clue at a time and identify if it is a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ example of the concept.

- Comparison ‘yes’ examples: Simultaneously share multiple ‘yes’ clues to have learners identify common attributes.

- Comparison ‘yes/no’ examples: simultaneously share one yes and one no clue for learner to distinguish critical differences.

- Organize the learners into small groups of 2-4.

- Model the process:

- Introduce the clue/set of clues.

- Give the group 3-5 minutes to list the characteristics of the single clue or the differences between the two clues.

- Have the group create a tentative hypothesis of their ideas to characterize the concept.

- Present the second clue/set of clues. Give groups 3-5 minutes to refine their list of characteristics/differences and refine their hypothesis based on what they have learned between rounds 1 and 2.

- Continue providing clues for ongoing discussion and refinement of their hypothesis of the concept.

- As a class, have each group share what they think the concept is by providing justification using their list of critical attributes.

- Facilitate a discussion that identifies the concept and breaks down the characteristics of its relationship to each clue.

Concept Attainment: Variations and Extensions

Scaffold learning:

- Encourage learners to write the characteristics of each clue on individual index cards or sticky notes. As new clues are presented, groups may move their index cards into yes/no categories to continue to refine their hypothesis.

- After each round of clues, have groups share their list of attributes to record and display a collective list of attributes.

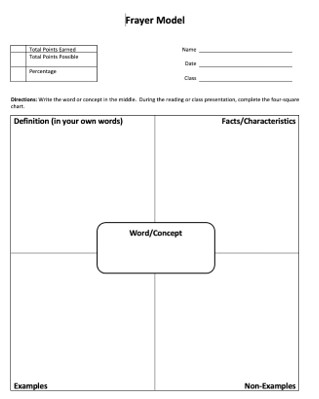

Formative Assessment Using Graphic Organizers: At the conclusion have leaners reflect on the core characteristics of a concept while organizing their thinking using a graphic organizer. Comparison organizers that integrate well with the Concept Attainment Strategy include:

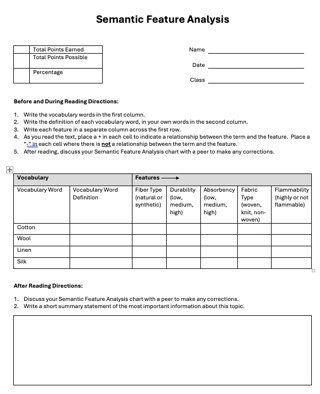

- Semantic Feature Analysis Chart: A Semantic Analysis Chart is a grid that helps learners to visually compare and contrast essential features of a concept to identify if the features are present or not (download at www.adlit.org).

- Frayer Model: A Frayer Model is a graphic organizer that requires learners to examine a concept by identifying essential and non-essential attributes as well as indicate core characteristics and draw a picture to remember the concept (download at www.adlit.org).

- T-chart: Organizes thinking into a ‘examples’ and ‘non-examples’ columns (download at www.readwritethink.org)

Extend learning: After groups have identified the concept and its attributes, challenge them to create their own clue(s).

Concept Attainment: Examples

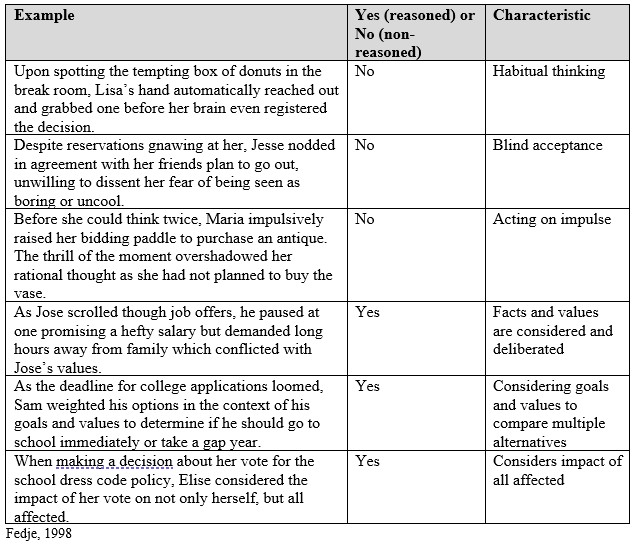

Topic: Characteristics of Practical Reasoning

National FCS Standard: Reasoning for Action Standard 1: Evaluate reasoning for self and others.

Example Clues for Key Attributes: Text (scenarios of an individual/family engaging in a reasoned vs. non reasoned thinking process)

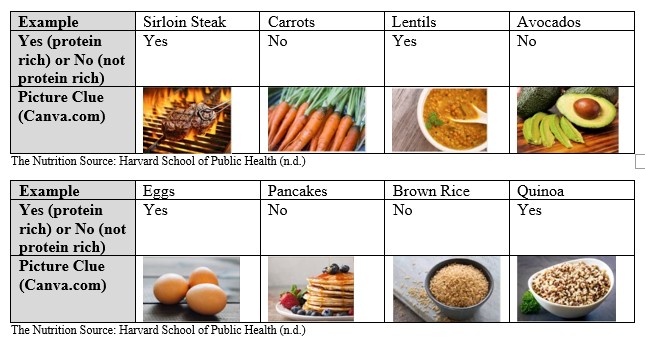

Topic: Protein Rich Foods

National FCS Standard: 14.2 – Examine the nutritional needs of individuals and families in relation to health and wellness across the lifespan.

Example Clues for Key Attributes: Pictures of Food Objects

Graphic Organizer Formative Assessment Extension: Frayer Model (available at www.adlit.org)

Facilitation: Provide learners with the Frayer model graphic organizer. Co-construct a definition of protein with them. Then, construct the Concept Attainment strategy challenging groups to consider if each food item is an example or a non-example while providing justification of facts/characteristics of foods that contribute to them being protein rich. After the activity, review learning to develop a refined list of core attributes.

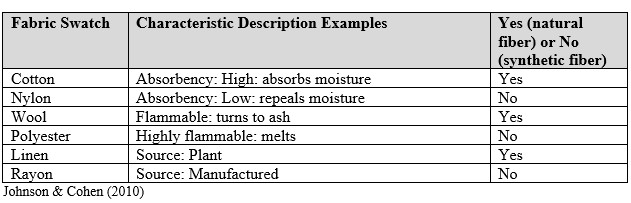

Topic: Characteristics of Natural Fibers

National FCS Standard: 16.2 – Evaluate textiles, fashion and apparel products and materials.

Example Clues for Key Attributes: Fabric Swatches

Graphic Organizer Formative Assessment Extension: Semantic Feature Analysis Chart (available at www.adlit.org)

Facilitation: Collect synthetic and natural fabric swatches. When conducting the Concept Attainment strategy, share foundational differences between natural and synthetic fibers, such as their source and core properties. A fabric swatch may be used more than once to continue building upon the characteristic list (e.g., cotton is both highly absorbent and from a plant). After debriefing about the core characteristics of natural fibers, distribute the Semantic Feature Analysis chart to for learners to synthesize their knowledge while comparing types of natural fibers.

Inductive Learning

Inductive learning was developed by Hilda Taba’s Concept Formation model of instruction (Joyce et al, 2017). It is sometimes called ‘bottom-up’ learning because it develops higher-order thinking skills by providing learners with a variety of artifacts (e.g., pictures, text examples, data, objects) and asks learners to infer knowledge and meaning by grouping them according to common attributes. When creating inclusive groupings, learners move from specific observations about the artifacts to making more generalized conclusions and predictions.

The ability to think inductively requires several thinking skills including flexible thinking, content knowledge to make associations, and the ability to classify and categorize (Silver et al., 2017). The development of these skills provides the foundation for independence as a learner when engaging in instructional methods commonly used in Family and Consumer Sciences classrooms including inquiry-based learning, problem-based learning, project-based learning, and case-based learning.

Inductive Learning: Planning and Conducting

The inductive learning strategy is a versatile strategy that enhances learning at multiple stages. At the beginning of a unit, it may be used to identify what learners already understand about a topic. The strategy is also effective as a formative assessment within a learning plan to review and assess a learner’s ability to group and classify information (Stobaugh, 2019).

Silver et al (2017), provide the following guidance when facilitating the inductive learning strategy:

- Identify the key concepts of a topic or unit of study that you want learners to understand or generalize about.

- Choose artifacts that support the key concept or generalization. Examples of artifacts include quotes, pictures, objects, data. When choosing artifacts ensure that they are specific with 3 or more artifacts per concept or generalization to allow for groupings.

- Ensure each artifact is separate (e.g., each quote on a separate index card) to allow learners to easily move the artifacts into different groupings.

- Have learners work individually or in a small group to begin organizing the artifacts into groups. Encourage learners to:

- Think flexibility about the attributes of an artifact to discover new relationships between items;

- Listen closely to peers to consider creative options for groupings;

- Be willing to adapt to make changes to grouping as new insights evolve;

- Consider if an artifact may belong to multiple groupings for different reasons.

- As learners create their categories, develop a short label that defines and describes the common attributes among the artifacts.

- As a large group, discuss the different groupings and rationale created. Focus on the similarities and differences between groups and how meaning was created.

Inductive Learning: Variations and Extensions

- Scaffolding: The number of artifacts may vary depending on the concept, instructional time, and developmental needs of the learner. For younger learners, 5-10 examples are recommended for older learners 15-25 examples may be appropriate (Stobaugh, 2019).

- Questioning: Use questions to help learners get ‘unstuck’ when creating groupings to move beyond the obvious and think critically about the similarities and differences among the artifacts. Questions may include:

- What do we know about the artifact?

- What artifact doesn’t quite fit with a group? Why? Can a new group be created using that artifact?

- What meaning did the author intend with the text?

- How does the descriptive title help a learner to understand the grouping?

- Concept Mapping: As a formative assessment, have learners create a concept map to show the relationships between the different categories created. Challenge learners to summarize their concept map by drawing conclusions about the core concept.

Inductive Learning: Examples

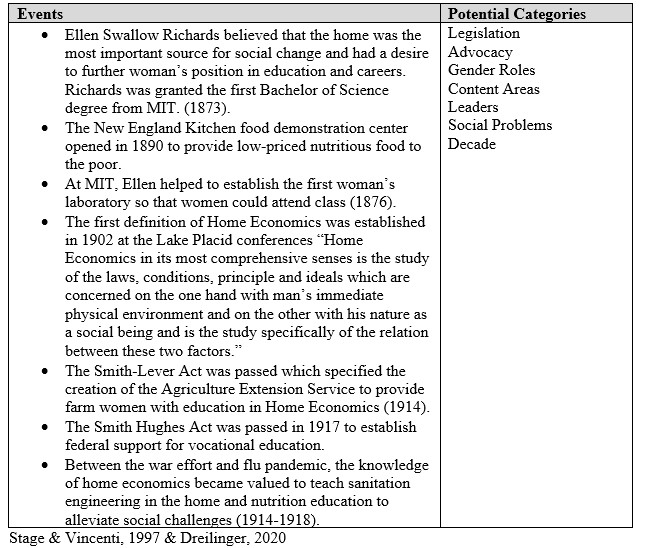

Topic: History of Family and Consumer Sciences

Artifacts: Event cards

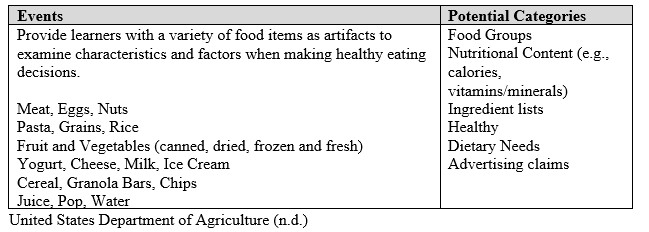

Topic: What is Healthy?

FCS National Standard: 14.2 – Examine the nutritional needs of individuals and families in relation to health and wellness across the lifespan.

Artifacts: Food Items

References

Anders, P. L. & Guzzetti, B. J. (2005). Literacy instruction in the content areas (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Carlson, S. & Johnson, J. (1999). Conceptual thinking. In J. Johnson & C.G. Fedje (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences curriculum: toward a critical science approach- Yearbook 19 (pp. 144-155). Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Comer, D., Hittman, L., & Fedje, C. (1997). Questioning: A teaching strategy for everyday life strategy. In J. Laster & R. Thomas (Eds.), Thinking for ethical action in families and communities (pp. 173-183). Family and Consumer Sciences Teacher Education Yearbook 17. Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Dreilinger, D. (2020). The secret history of home economics: How trailblazing women harnessed the power of home and changed the way we live. W.W. Norton & Company.

Epper, M. J. (2006). A comparison between concept maps, mind maps, conceptual diagrams and visual metaphors as complementary tools for knowledge construction and sharing. Information Visualization, 5, 202-210. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ivs9500131

Fedje. C. G. (1998). Helping learners develop their practical reasoning capacities. In R. Thomas & J. Laster (Eds.), Inquiry into Thinking (pp. 29-46). Family and Consumer Sciences Teacher Education Yearbook 18. Glencoe/McGraw-Hill.

Fedje. C. G. (1999). Program misconceptions: Breaking the patterns of thinking. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences Education, 17(2), 11-19.

Harvard (n.d). The nutrition source: What should I eat?. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/what-should-you-eat/

Holcombe, M. & Fedje, C. (1983). The TLP: An approach to planning. Journal of Vocational Home Economics Education, 1(1), 39-48.

Johnson, I. & Cohen, A., (2010). J.J. Pizzuto’s Fabric Science. Fairchild Books.

Johnson, J., Carlson, S., Kastl, J., & Kastl, R. (1992). Developing conceptual thinking: The concept attainment model. The Clearing House, 66(2), 117-121. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.1992.9955947

Joyce, B., Weil, M., & Calhoun, E. (2015). Models of teaching (9th ed.). Pearson.

Laster, J. F. & Johnson, J. (2001). Major trends in family and consumer sciences. In J.F. Laster & J. Johnson (Eds.), Family and consumer sciences: A chapter of the curriculum handbook (revised and updated., pp. 3-20). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Merriam-Webster (n.d.). Concept. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/concept

Montgomery, B. (2008). Curriculum development: A critical science perspective. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 26(National Teacher Standards 3), 1-16.

Nourish (n.d.). Food systems tools: Food system map. https://www.nourishlife.org/teach/food-system-tools/

OpenAI. (2024). ChatGPT (3.5) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com

Silver, H. F., Strong, R. W., & Perini, M. J. (2017). The strategic teacher: Selecting the right research based strategy for every lesson. ASCD.

Stage, S. & Vincenti, V. B. (1997). Rethinking home economics: Women and the history of a profession. Cornell University Press.

Stobaugh, R. (2019). 50 strategies to book cognitive engagement: Creating a thinking culture in the classroom. Solution Tree Press.

Swafford, M. & Rafferty, E. (2016). Critical thinking skills in family and consumer sciences education. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 108(4), 13-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.14307/jfcs108.4.13

United States Department of Education (n.d.). Food availability and consumption. Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/food-availability-and-consumption/

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Pearson.