2 I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For

Discovering the Self

Meet Leslie

Leslie is a communication studies major at a college a few hours away from her hometown. She is the oldest of three kids and was nervous to leave home since her family has always been close and she has never liked big changes. But, after the first few months in her dorm, she feels less anxious and is adjusting well to college life. Leslie loves to read, draw, and play video games with her closest friends when she doesn’t have any homework to do after class, and has developed a new interest in plants thanks to her roommate who is growing some on their shared window sill. She is enjoying most of her classes, especially the challenging ones, and hopes to join the debate team after midterms. She has never done debate before, but her roommate is on the team and it seems like a fun way to hone one’s public speaking skills. Leslie continues to learn new things about herself each week and starts to think about the characteristics she shares with her family, friends, and mentors, along with the characteristics that seem to be totally unique to her. College has broadened her horizons quite a bit and even though that can be startling sometimes, it mostly feels like she is growing into herself.

Investigating Identity

Have you ever felt like Leslie does—like she’s “growing into herself” as she starts a new chapter of her life? For many people, changes always seem to prompt questions like “Who am I?” and “Who will I be after ____?” Understanding identity, who you are and how you see yourself, is essential to people from all walks of life, and to the discipline of communication studies. Before you can assess the quality of your intra- and interpersonal communication, you must learn about yourself and begin to build an understanding of who you are.

Parts of your identity will shift over time due to a number of influences, including culture, past and future experiences, and shifting elements of your self-concept. During times of change, such as moving to college like Leslie, or experiencing a loss in the family, starting a new job, or making a new friend, you have the opportunity to rediscover yourself and how you are also shaped by outside forces.

Identity is at work both inside and outside of the body at all times. Identity management is how you share your identity with others through your verbal, nonverbal, and written interpersonal communication. In turn, others will share themselves with you, creating a relationship in which you both influence one another’s identities over time. Just as Leslie has been impacted by her roommate, the roommate is likely impacted by Leslie’s character, interests, and behaviors. In this chapter, you will learn about identity, elements of the “self,” and how viewing ourselves as distinct from others while honoring their unique “selves” is an essential part of communicating in all kinds of relationships.

2.1 Perception

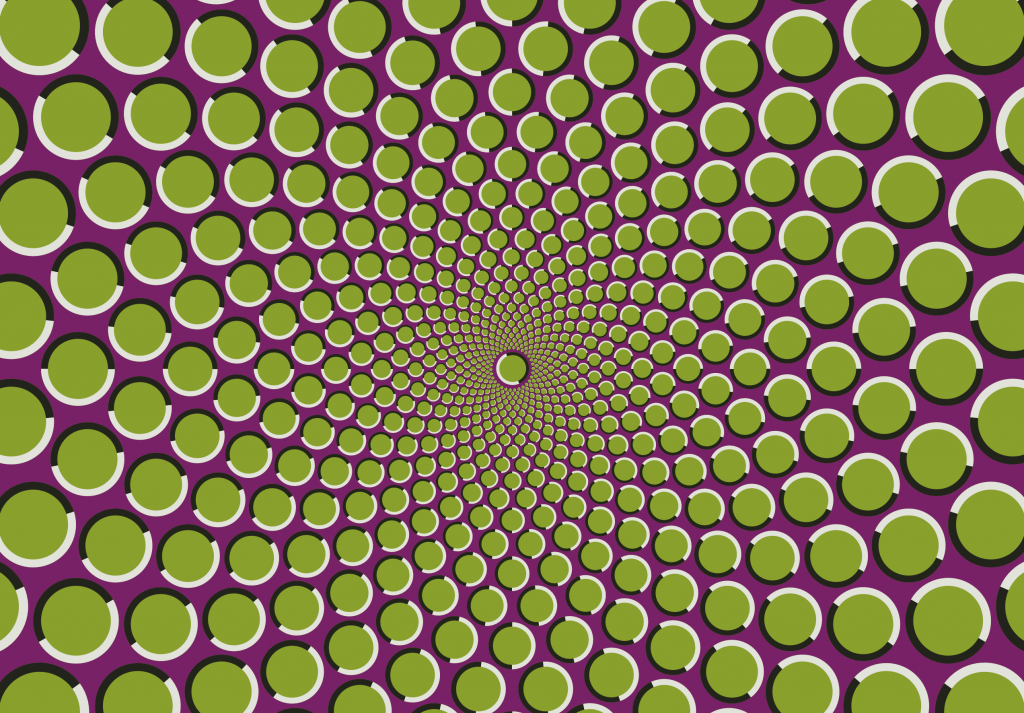

What do you see when you look at the image above? Does it seem to be in motion?

There are plenty of popular optical illusions that have been around for years, some of which were created accidentally and not purposefully designed to trick the mind into believing that the image can move or change with a blink—they just happen to appear to shift under just the right light. Even when the image is still, we can know that it is fixed and still perceive that it is moving.

Perception is the way that you attend to, organize, and interpret information in your environment, including messages from others and sensory indicators like smell or touch. Perception occurs in three parts: (a) you attend to or select a piece of information in the environment; (b) you organize that information by situating it in what you already know, such as what you have been taught or what your intuitive responses are; and (c) you interpret the organized information by assigning meaning to it. Interpretation is often followed by a response behavior or, in the case of interpersonal encounters, feedback to a sender.

For example, if you feel a hand touch your arm (attend/select), then remember what you have been taught about reasons someone might touch your arm and what you do or do not know about the person doing so (organize), then you may assign meaning to the touch (interpret) as being a friend’s attempt to comfort you or a stranger’s way of gently letting you know that they’re passing behind you.

While most of this perception occurs very quickly and often subconsciously, it is an important part of being able to survive and interpret situations of varying complexity and severity, and it allows one to “read” interpersonal encounters. Importantly, much like the optical illusion above, perception is not always correct—you may not be able to accurately perform one, some, or all of the steps of perception in a given situation. In other cases, you may not want to admit that what you are perceiving is actually happening. However, when you put in the work to accurately perceive situations and their components, you are setting yourself up for gaining a more accurate understanding of those situations and their implications.

How do we perceive and present identity?

If identity is “who you are and how you see yourself,” then you must be able to perceive your own identities in order to communicate them, right? Some parts of your identity might be easier to understand, such as your position in your family (e.g., child, sibling, parent), while others may be more difficult to fully grasp, like your gender identity or sexual orientation. Because identity is often dynamic, you may see yourself now in a way that will be different from how you see yourself in five years. Time is a major agent in the ongoing clarification of our self-perceptions.

We are taught to perceive our identity through communication. You can learn about your own identity by interacting with others, or observing them, and through consumption of media. Social Identity Theory explains that your sense of who you are is largely shaped by these interpersonal encounters and the groups to which you belong (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). So, the way values that your family passes on to you, affiliation with a group like an ethnic group or faith community, and even your intramural sports team can impact the identity you hold and share with others.

It is critical, though, that we give others the chance to communicate their identities to us because very few identity components can actually be perceived with visual information. If you see someone in a firefighter’s uniform, it is highly likely that they are a firefighter. However, if you pass someone on the street, you may not be able to determine their abilities (e.g., can they hear you?), beliefs, ethnicity, sexuality, gender, age, marriage status, etc. Making assumptions about someone’s identity can be harmful or hurtful, so communicating with others and letting them self-identify (e.g., asking them for their pronouns, allowing them to tell you about their background on their own terms) is a great way to maintain a healthy conversation and respect their identity while avoiding misperceptions.

2.2 The Self

When working to understand the self, it is important to break down the elements of self into more digestible parts. Though parts of the self are not necessarily totally distinct from one another (e.g., there are going to be connections between self-concept and self-esteem; King, 1997), it is possible to pin-point where different parts of the self shine through. Self-concept includes attributes one perceives in the self without value-assessments (e.g., I play tennis, I spend a lot of time in school, I am part of a big family), whereas self-esteem includes perceptions of the self that are rooted in value assessments (e.g., I am not very athletic, I am very smart, I am usually good at providing support to others in times of need). Self-efficacy, which is sometimes used interchangeably with self-confidence, is the degree to which one believes they can perform a task or behavior successfully (Bandura, 1977). All of these components of the self come together to form a complex identity, leading us to ask questions such as: Who are you? How strong are some of your qualities or abilities? How well can you perform a skill, task, or behaviors? How might you change from one day to the next?

Self-Expansion Theory

One way to address some of those questions and how they may impact our relationships is through the application of Self-Expansion Theory (SET). Developed by Arthur and Elaine Aron (1986), SET argues that being in close relationships can actually increase one’s sense of efficacy, and that humans are naturally motivated to seek an increase in efficacy so they have more access to and opportunities to explore the world. SET also accounts for the inclusion-of-other-in-the-self principle, which is the idea that being a relationship with someone else requires that one experience the other person’s self—their take on life, values, use of resources—almost as if two people create a new, more complex unit with two overlapping selves (Aron et al., 2013). In this way, close relationships can enhance one’s life when the sense of self is expanded through closeness with another person. Though close relationships can also be painful if they come to an end and force a separation of one’s self from another, the potential gain often outweighs the potential loss. Self-expansion occurs when children interact with guardians or teachers, when young people begin their first careers and interact with co-workers, and when individuals pursue meaningful friendships and romances; thus, self-expansion occurs throughout the lifespan (Aron et al., 2013). Relationships with others can shape the self—and identity—in many ways. One major influence on identity is culture.

2.3 Culture, Identities, and Difference

Culture can be very tricky to define, mostly because it is connected to nearly every aspect of life (Faulkner, et al., 2006). Beyond being just a way of living, culture includes the ways one is taught to believe, behave, speak, relate, organize, and interact at the personal, professional, social, and political levels. Culture may include more concrete things like foods or holidays, but it can also be abstract—such as a cultural emphasis on freedom—and difficult to pin down. Most people identify with cultures that are, to some extent, geographically relevant to them; from the cultural holdings of one’s city all the way to the nation or country in which one lives, culture exists at every level of personhood. One’s family and friends often encourage the adoption of a culture or multiple cultures.

Individuals often identity with subcultures as well, which are pockets of unique culture situated in the larger culture with which a specific group of people in a larger culture may identify. Subcultures may include people who engage in a certain activity or behavior (e.g., motorcyclists), advocate for something (e.g., climate crisis activists), or enjoy a certain type of media or fashion (e.g., goths). Some subcultures are more well-received among the general public than others, and some may become more mainstream over time and basically melt into the culture at large. Being a part of cultures or subcultures can greatly impact one’s identity and expectations about relationships.

Though there are many ways to assess how a culture may shape the identities of people who live in or are exposed to it, one of the most popular ways to classify cultures is to label them low or high context cultures (Hall & Hall, 1990). In low-context cultures, people tend to say what they mean, using words and linguistic details to convey a message. In high-context cultures, communicators depend on the context in which the message is delivered (i.e., nonverbal signs and symbols, the time and place) to embed meaning in the message rather than the literal words of the message. Cultures can also be classified as being more feminine or masculine, with masculine cultures placing an emphasis on power hierarchies, competition, and assertiveness, whereas feminine cultures emphasize a community-minded approach to communication and people caring for one another despite roles or identities (Hofstede, 2001).

Reflection Questions

How would you describe the culture or cultures you grew up in?

How do you think they have shaped your relationships?

Studying cultures and subcultures is just one way to understand how people bring their identities into relationships. Individuals also enter relationships with frames of reference, or ideas about what a relationship or situation could or should look like based on previous experiences. For example, if someone had a rocky upbringing, they may have a complicated and largely negative frame of reference for how familial relationships might function. Frames of reference can change, expand, or be reinforced with every new experience. It can take time for someone to adjust to a relationship that is more positive than their frame of reference, or a relationship may not last very long at all if it is more negative. What someone has experienced in previous relationships can be used to predict how they will behave in the future, making frames of reference an essential part of identity.

Physiological and physical identities are also important to consider. One’s ability to engage in the five major senses (touch, smell, taste, hearing, sight), height and weight, mental and physical wellbeing, skin tone, athleticism and other body-centered characteristics may greatly impact one’s identity and approach to relationships. For example, about one million people in the U.S. use American Sign Language (ASL) (Waterfield, 2019), about half of whom have some degree of hearing loss (Lacke, 2020). This means that roughly 0.1% of people in the U.S. can communicate using ASL, forcing those who use ASL as their primary mode of communication to resort to other forms (e.g., writing a message down, using text-to-voice) just to get their message across in everyday situations. For people who identify as having a disability that impacts their day-to-day lives, they may perceive their disability as a salient part of their overall identity, one that others may focus on. Other physiological and physical considerations, such as skin tone, and whether one is subject to experiencing racism or privilege based on their skin tone, may shape how one perceives their identity and how salient that physical consideration becomes in day-to-day interactions.

Further, Kimberlé Crenshaw’s (2006) concept of intersectionality reminds us that some people must navigate tensions between identities or face exaggerated societal oppressions due to overlaps in multiple identities. Crenshaw focuses specifically on the experiences of Black women who face the systemic violence and oppression that Black people are subjected to, the sexism and misogyny that women deal with in today’s society, and a combined oppression that is unique to Black women. This third space contains oppressions rooted in stereotypes about Black women, systemic failures that limit their access and resources, and social inequities that impact Black women differently than Black men and people of other races/ethnicities. One major takeaway from Crenshaw’s work is that people often hold identities that are connected in very complex ways that we may never be able to fully understand through our own eyes. Relationships are benefitted by approaching others with empathy, asking them to share about their identities before making assumptions, and creating a space for identities to be messy rather than forcing people to fit them neatly in a box—doing so helps us grow together.

2.4 Identities We Attribute to Others

When Leslie (from the beginning of the chapter) moved into the dorm with her new roommate, it probably seemed out of the ordinary to have plants in the room. Something that her roommate was clearly used to was out of the norm for Leslie. Norms and mores, first impressions, and stereotypes are only a few of the social phenomena that impact how we see other people and attribute identities to them.

Norms are expected behaviors or social responses that correspond to certain situations. For example, if a student has a question, they might raise a hand so the teacher will call on them. Or, if Leslie announced to her friends that she made an A+ on an exam, they might congratulate her on her success. The ways that an individual does or does not adhere to norms can shape how others perceive their alignment with cultural values, what is considered polite or correct, and ultimately whether they would be a good relational partner.

In similar ways, first impressions—the conclusions made about a person in a first encounter—can shape our perceptions of others, even if it’s in ways that seem superficial (e.g., this person held a door open for me on my way in, so they must be generally polite). First impressions are important because the inferences we make about others can influence how we behave towards and around them long-term (Over et al., 2020). Additionally, according to Charles Horton Cooley’s (1902) theory of the Looking Glass Self, one person’s sense of self is likely shaped by how they think other people see them. In that case, Person A’s first impression of Person B could even become part of Person B’s sense of self. Thus, how we communicate our impressions of others matters.

Stereotypes are assumptions or generalizations made about a group of people and, as a result, individuals who are a part of that group. Stereotypes are often inaccurate, and while they can be positive or negative, many are harmful. Avoiding the use of stereotypes when assessing others’ identities may lead to a deeper, more accurate understanding of new acquaintances and a better relationship in the long run. Recognizing how one may have used stereotypes to make sense of another person’s life and experiences may encourage us to rethink the way we perceive potential or current relational partners.

Closing Questions

How do the concepts in this chapter connect to each other?

How does combining them give you a better grasp on identities?

What is an example of how you or a friend have navigated a changing identity?

The Chapter 2 Mixtape

-

-

Pearl Jam – “Who You Are”

-

Madonna – “Express Yourself”

-

Eric Carmen – “All By Myself”

-

Simon & Garfunkel – “I Am a Rock”

-

Gino Vannelli – “Living Inside Myself”

-

Chapter References

Aron, A. & Aron, E. (1986). Love and the expansion of self : Understanding attraction and satisfaction. Hemisphere Pub. Corp.

Aron, A., Lewandowski, G. W., Jr., Mashek, D., & Aron, E. N. (2013). The self-expansion model of motivation and cognition in close relationships. In J. A. Simpson & L. Campbell (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of close relationships (pp. 90–115). Oxford University Press.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. Scribner.

Faulkner, S. L., Baldwin, J. R., Lindsley, S. L., & Hecht, M. L. (2006). Layers of meaning: An analysis of definitions of culture. In J. R. Baldwin, S. L. Faulkner, M. L. Hecht, & S. L. Lindsley (Eds.), Redefining culture: Perspectives across the disciplines. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hall, E. T., & Hall, M. R. (1990). Understanding cultural differences: Germans, French and Americans. Intercultural Press.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage.

King, K. A. (1997). Self-concept and self-esteem: A clarification of terms. The Journal of School Health, 67(2), 68-70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1997.tb06303.x

Lacke, S. (2020, August 5). Do all deaf people use sign language?. Accessibility.com.

Retrieved from: https://www.accessibility.com/blog/do-all-deaf-people-use-sign-language

Over, H., Eggleston, A., & Cook, R. (2020). Ritual and the origins of first impressions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 375(1805), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0435

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In M. J. Hatch & M. Schultz (Eds.), Organizational identity: A reader (pp. 56-65). Brooks/Cole.

Waterfield, S. (2019, April 15). ASL Day 2019: Everything you need to know about American Sign Language. Newsweek. Retrieved from: https://www.newsweek.com/asl-day-2019-american-sign-language-1394695

who you are and how you see yourself.

how you share your identity with others through your verbal, nonverbal, and written interpersonal communication.

The way that you attend to, organize, and interpret information in your environment, including messages from others and sensory indicators like smell or touch.

Attending to a piece of information in the environment.

situating the information you select in the context of what you already know, such as what you have been taught or intuition.

assigning meaning to information.

This theory explains that your sense of who you are is largely shaped by interpersonal encounters and the groups to which you belong (Tajfel & Turner, 1979)

Attributes one perceives in the self without value-assessments (e.g., I play tennis, I spend a lot of time in school, I am part of a big family).

Perceptions of the self that are rooted in value assessments (e.g., I am not very athletic, I am very smart, I am usually good at providing support to others in times of need).

The degree to which one believes they can perform a task or behavior successfully.

being in close relationships can actually increase one’s sense of efficacy; humans are naturally motivated to seek an increase in efficacy so they have more access to and opportunities to explore the world, and being connected to others helps them achieve that.

Beyond being just a way of living, culture includes the ways one is taught to believe, behave, speak, relate, organize, and interact at the personal, professional, social, and political levels. Culture may include more concrete things like foods or holidays, but it can also be abstract—such as a cultural emphasis on "freedom" or "happiness."

pockets of unique culture situated in the larger culture with which a specific group of people in a larger culture may identify.

people tend to say what they mean, using words and linguistic details to convey a message.

communicators depend on the context in which the message is delivered (i.e., nonverbal signs and symbols, the time and place) to embed meaning in the message

emphasis on power hierarchies, competition, and assertiveness

community-minded approach to communication and people caring for one another despite roles or identities

ideas about what a relationships or situation could or should look like based on previous relational experiences

some people must navigate tensions between or face exaggerated societal oppressions due to overlaps in multiple identities; Crenshaw (who developed the concept of intersectionality) focused on Black women's experience of being Black, women, and Black+women.

Expected behaviors or social responses that correspond to certain situations.

The conclusions made about a person in a first encounter.

Charles Horton Cooley’s (1902) theory that argues that one person’s sense of self is likely shaped by how they think other people see them.

Assumptions or generalizations made about a group of people or individuals in a group.