Changing Focus: Using Photography to Prompt Creative Writing

Rasma Haidri

Poets are sometimes asked why they write poems. My answer to that question involves a metaphor from photography. In poetry I try to freeze-frame a moment, capture a scene in an effort to unpack its meaning and explore its significance. A successful poem’s meaning is always greater than the sum of its parts. The same is true for photography.

Each photograph contains a scope of meaning that only partly consists of what is pictured in the frame. There is a comment made before the photo was taken, the reason people were gathered, the significance of an object, and so on. We talk about these aspects of photos whenever we share them with others: by their very nature they prompt us to talk about our memories.

Photos also prompt good writing. It is obvious to write about the memory a photo invokes; for this exercise we move beyond mere memory in an effort to shift the paradigm of what it means to look at a photo. We change the way we look, then write about what’s there. It’s about perceiving more deeply both inside and outside the frame. In recent years our relationship to photography has changed due to the ease of taking digital photos. We are inundated with them and risk becoming desensitized to really seeing them. This exercise encourages a greater appreciation for photography as a visual poetic text, while generating raw material for creative writing.

As with any writing prompt, a photograph can be used as an antidote to writer’s block. Photographic prompts circumvent the thinking processes that hinder creativity. They force the writer to make intuitive leaps. “Changing Focus” can be used with personal snapshots as well as with photos the writers have not seen before. Personal photos usually result in more sensitive personal writing, but both known and unknown photographs can access an individual’s creative core and express the student writer’s singular voice.

The aforementioned approach to a photograph—writing about what is in it—can result in the purely factual: that’s my mother and father, or purely imaginative: Martians Rleepo and Froop appeared in the guise of an old married couple. There’s value in practicing both extremes of that spectrum as warm-up exercises: render the photograph as “just the facts, ma’am” and pure fancy. As practice exercises these are not related to specific outcomes any more than sit-ups are related to the outcome of a tennis match. Changing Focus is rooted near the factual end of the spectrum. It’s about authentic experience, not artful cleverness.

Step-by-Step Instructions

- Time the students’ writing session. Timing the writing sessions can help circumvent self-censorship and overthinking. Timed sessions can be as short as three minutes or as long as thirty.

- Select photos using one of the following strategies:

- Hand out the same photo to all the writers.

- Create a classroom bank of photos the teacher and/or students have collected; each student is given a random photo.

- Display the classroom bank of photos and let each student select the one that appeals most.

- Ask students to bring in a favorite personal photograph.

- For each freewriting session (timed or untimed), combine a physical photo and one of the prompts below. They are in no particular order.

Prompts

- Write down the who, what, when, where, why of the photo. The facts, the visible and invisible settings, what you know of the situation and story. Spend time looking at the photo. Are your eyes drawn over and over again to one part of it? If so, write that down and try to describe it. If you start writing about something that’s not in the photo, allow yourself to follow the idea.

- Choose one object or person in the photo as a prompt for a twenty-minute freewrite. Allow your writing to wander away from the object or person you have started with. At the end of the session, read through the raw material, underlining words and phrases that strike you as meaningful, surprising, energized, interesting. Start a new piece of writing with these.

- Describe each object in the picture as if you are drawing it. Don’t miss anything. For example: there are men in a boat, but you don’t see their feet, and in the water there is the shadow of the men in the boat, and one holds a flower but it is shaped like a star, or like a toy water pistol you once had. Write a slow description of what you see (and what it reminds you of) while keeping your hand writing and your eyes on the photo.

- Let your attention be drawn to a part of the photo, then write as much sensory detail about it as you can.

- Write about what is not in the picture, but is noticeable in its absence. What could or should be there. (The absent parent, the lack of shoes on the children’s feet, the child not yet born, the rescue helicopter with the blades turned off, etc.)

- Think about the point of view of the photographer. Why has the photographer taken this? Write about what might have made someone decide this scene was worth capturing.

- Think about the moment after the picture was taken. Write about how people moved away and repositioned themselves in other places, how they separated into different groupings that have been forgotten because no one photographed them. What was said that was never recorded?

- Find an object in the picture that is familiar to you. Maybe there is a toy bear in the corner of the bookshelf. The photo might be of a class reunion, but you write about the random object, what it meant to you, what questions you have for it, what it would want to say to the people present, to you today.

- Make a list of every item in the photo. Then make a list of what is not in the photo. Write ways in which these lists overlap or have a connection.

- Choose ten words that are in the photo (broken dinner plate, stone, fallen leaf, girl’s shoe, new car, etc.) and use one in each line of a poem.

- Start a piece of writing with the line, “This is not the photograph I would take…” Respond to the photo by describing a fantasy makeover of it.

- If the photo is about people you know, write down a funny, important, or sad thing you remember about one of them. Then write to create a connection between your memory of the person and the photo.

- If the photo contains strangers, write about how the person in the photo is not you. If the photo shows a dining family, start with a line such as, “I can’t remember when I last ate…”

- Write every thought, feeling, emotion, question, reaction you have to just looking at the picture. This could go on for pages. When you are done looking at the photo, read over what you have written. Take the parts that jump off the page at you and start the poem with these.

- Write about what happened before the picture was taken. What led up to this photo being shot? What were people doing or saying? Who didn’t get in, or just part of their body got in the frame?

- Write as if you are the photograph speaking to the people in the frame. Let the photograph speak to the person who took the picture, or to you the viewer.

- Write a dialogue between two people or objects in the photograph.

- Write about the photo by imagining it ten years from now, or ten years after it was taken. What objects are changed? What people are different? How have people changed?

- Spend a minute looking at the picture, then turn it over and write about what you remember in as much detail as possible.

- Write down twenty unique titles or captions for the photo. Choose one and use it as the first sentence in a piece of writing.

Example of the Exercise

The facts in the frame:

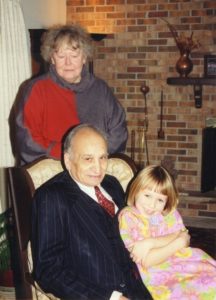

It’s a photo of my parents with my daughter.

The visible setting:

It’s a photo of my parents and my daughter in my living room.

The not visible setting:

It’s a photo of my parents and my daughter in my living room

at my mother’s seventieth birthday party.

Ho-hum. So far this is not a photograph worth talking about. It’s only of slight interest to me. But there’s more.

The situation and story:

It’s the last photo ever taken of my father.

He died the next day, totally unexpectedly.

I’m still not there. Poignant as they are, these boldface words are facts I already know. I can only arrive at the truth the photograph holds (what I don’t know that I know) when I explore it as a writing prompt.

With the photo below, I used the prompt: “Write about what happened the moment before the picture was taken.” The resulting poem follows.

The Last Photograph of My Father

By Rasma Haidri

My daughter is in his lap

like a bouquet of flowers, the bouquet

that will come from a friend

three days later,

but that is not the miracle.

The miracle is my mother

behind his chair. No one asked her

to stand there—

not because she doesn’t belong,

but my mother refuses to be

in pictures,

turns her head, covers

her face, scowls.

A childhood snapshot shows her hitting

the camera.

Even in a wedding photo she waves

an angry arm at the photographer.

No one asks to take my

mother’s photo.

This was to be of my father and daughter,

but she got up unbidden,

crossed the room,

positioned herself behind him,

and though unpracticed, she smiled,

wanting to be there, as if she heard

his heart counting down.

It was a joke in our family that our mother hated to have her picture taken. We’d point the camera her way just to tease her into stomping a foot and waving an arm so the cigarette smoke trailed overhead. As years passed the joke grew old and we no longer bothered to try. On her seventieth birthday I hosted a small gathering. My father who lived in another state was up for a visit. Something was in the air, because no one wanted the day to end. My uncles didn’t even leave to watch the Super Bowl. Near evening I spied my daughter sitting in my father’s lap and took up my camera to snap a picture of them. As I adjusted the exposure to take one more, a matter of seconds, my mother got up, put out her cigarette, crossed the room to stand with them. She wanted to be in the picture? Strange. I didn’t say anything. I took the picture.

His death the following day rocked the very foundation of the world I had always known, a world that had revolved around my parents’ turbulent marriage. Not until the writing exercise did I discover what I had never really believed—my mother had loved my father.

Biography

Rasma Haidri grew up in Tennessee and makes her home on the Arctic seacoast of Norway. She is the author of the poetry collection As If Anything Can Happen (Kelsay Books, 2017) and three college textbooks. She holds an M.Sc. in reading education from the University of Wisconsin and is an MFA candidate at the University of British Columbia.