Fantastic Characters and Where to Find Them: A Generative Exercise for Classrooms Exploring Narrative Structure, Worldbuilding, and the Cultivation of Character

Claire Agnes

Many of today’s undergraduate writing students have grown up with an affinity for the fantastic. The success of books like Harry Potter, Percy Jackson, Lord of the Rings, and Game of Thrones, coupled with the popularity of authors like Aimee Bender, M.T. Anderson, Laini Taylor, Kelly Link, and Holly Black, indicate a desire to engage with narratives that transport and transform. Many of my students enter the classroom with the fifth book of a fourteen-part epic series tucked under their elbows, fingers itching toward the pages while we discuss craft. These popular series are epic in their scope, ideas, and plot. They detail magical worlds full of imagination and adventure, characters layered in the history and conflicts of their empires, power struggles between rival groups, and duels that spark and captivate.

This exercise utilizes the largesse of the fantasy genre to help students explore fundamental elements of craft, storytelling, and character construction. By approaching these facets of narrative through the fantastic, the magical, and the absurd, students can practice critical building blocks of narrative using creative, nonlinear methodology. Fantasy stipulates that all worlds are possible. This freedom allays student insecurity regarding rendering realistic, dynamic, and nuanced characters. The step-by-step guided worldbuilding process of this exercise helps free students from linear thought in favor of spontaneous creation. Once the details of the world have been established, the students have enough raw material to form a protagonist and general narrative arc that suits such an environment. By first creating the world, culture, and creatures, students build narrative conflict and tension that can later be explored by their hero, who is developed during the final stages of this exercise. Students approach each component of fantastic worldbuilding through micro building blocks of detail, allowing for spontaneous creativity and invention without the weight of an entire proverbial world on their shoulders.

Step-by-Step Instructions

Part I: Introducing “The Hero’s Journey” (20 Minutes)

This first component of the exercise will familiarize students with the structure of Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. Students will relate the theory of the monomyth to popular works, connecting narrative structures across other media.

- Introduce students to Joseph Campbell’s theory of the monomyth, from his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. The original structure uses seventeen steps, but I have found students most receptive to the adapted twelve-step structure detailed by Christopher Vogler in the Twelve-Stage Hero’s Journey. Instructors may choose to write each step on the board, make up a handout detailing each step, or print one of the many graphics available online. Students will need to refer to these steps later in the exercise, so a list should be handy for their reference. In the context of this exercise, the Hero’s Journey will refer to the following steps:

- Ordinary World

- Call to Adventure

- Refusal of the Call

- Meeting the Mentor

- Crossing the Threshold

- Tests, Allies, Enemies

- Approach to the Inmost Cave

- Ordeal

- Reward (Seizing the Sword)

- The Road Back

- Resurrection

- Return with the Elixir

- After introducing the Hero’s Journey in general terms, go through each step and apply it to a well-known movie or book. A popular choice for this is Star Wars:

- Ordinary World—Luke is farming on the desert planet Tatooine.

- Call to Adventure—Luke finds the fateful message stored in R2-D2: “Help me, Obi-Wan Kenobi. You’re my only hope.”

- Refusal of the Call—Once he finds Obi-Wan Kenobi, Luke refuses to join the rebellion, saying he has work to do on Tatooine.

- Meeting the Mentor—Although Luke has already met Obi-Wan in the desert, Obi-Wan does not assume the role of mentor until Luke comes to him after having found his (Luke’s) home burned and family murdered.

- Crossing the Threshold—Luke leaves home and is immersed in the new world of the Mos Eisley spaceport.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies—Luke hires Han Solo and Chewbacca. When the stormtroopers try to stop them from leaving Tatooine, Luke escapes with their help.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave—Obi-Wan begins Luke’s education on the way to Alderaan. They find the planet destroyed and replaced by the “Inmost Cave,” the place of most danger: the Death Star.

- Ordeal—Luke and his allies rescue Princess Leia, though not without losing Obi-Wan, who is killed by Darth Vader.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword)—Luke already has a sword from Obi-Wan, so this step takes the form of Luke joining the rebel fleet as a pilot.

- The Road Back—In this step, the hero typically returns home. In this series, the sense of “home” is much larger and consists of a world without the threat of the Empire and the Death Star. Luke chooses between his personal needs and the greater needs of the rebellion when he says no to Han Solo’s offer to leave, signaling that Luke’s “road back” is contingent upon the destruction of the Death Star.

- Resurrection—Luke succeeds in destroying the Death Star and trusts the power of the Force, beginning his transformation into a Jedi.

- Return with the Elixir—Luke returns to his friends, symbolizing the continued hope of the rebel army. Princess Leia presents Luke with a medal.

- Break students up into small groups (two to three students per group, depending on class size). Ask students to pick a popular movie, book, or television series. It can be helpful to have some suggestions on hand if students show difficulty settling on a specific example. Students will then come up with the corresponding plot points for each work in accordance with the steps of the Hero’s Journey. Some popular examples from previous classes include Harry Potter, The Lion King, and Stranger Things.Not all texts selected will fit seamlessly into this formula. Some may omit certain steps, while others may play with the sequencing of events. The goal of this exercise component is to familiarize students with the arc of the Hero’s Journey, so divergences in plot can be productive teaching moments. Instructors may lead students in a further examination of these differences by discussing how these differences are reflective of the plot, character, world, or thematics of this particular work. Ask certain groups to share or, if time permits, go around the room and have each group present.

Example of the Exercise

The stages of the Hero’s Journey, as applied to The Wizard of Oz:

- Ordinary World—Dorothy is in Kansas and bored with it.

- Call to Adventure—Miss Gulch yells at Dorothy and Toto.

- Refusal of the Call—Dorothy runs away to protect Toto. She tries to turn back but is picked up by a magical cyclone.

- Meeting the Mentor—After accidentally killing a witch, Dorothy meets Glinda the Good Witch, who gives her advice on getting home.

- Crossing the Threshold—Dorothy heads on down the Yellow Brick Road.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies—Dorothy keeps having to escape the Wicked Witch of the West, but not without some help. She’s accompanied on her journey by Toto, the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and the Lion.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave—The Wizard of Oz says he will help them if they bring him the Wicked Witch’s broomstick. They are chased by horrifying flying monkeys.

- Ordeal—Dorothy and the Wicked Witch have it out. Luckily, there’s a bucket of water on hand, which Dorothy uses to melt the Wicked Witch. When they return to the Wizard with the broomstick, they realize he is nothing but a man behind a curtain with a good lighting rig.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword)—Dorothy and her friends realize they had what they sought inside themselves all along.

- The Road Back—Dorothy taps her ruby slippers three times.

- Resurrection—Dorothy resurfaces in Kansas.

- Return with the Elixir—Dorothy reunites with her family, instilled with a new appreciation for her life in Kansas, and says, “There’s no place like home.” Her good actions presumably reverberate through Oz and the real world. There’s no direct resolution to the Miss Gulch conflict, but Dorothy’s emotional transformation serves as such.

Part II: Worldbuild Your Way into a Narrative Arc (30–45 Minutes)

In this second component, students will create entire fictional empires from the outside in. They will form a protagonist and chart their narrative arc, but only after they have formed a rich bank of details from which to source their character’s main conflicts, aspirations, and abilities. For this exercise, it is best to provide students with a blank sheet of paper. Students may use their own writing utensils, but this exercise works most effectively if the teacher brings in markers, crayons, or colored pencils. This switch from typical writing materials helps to break students from classroom-related insecurity. Furthermore, the use of color can stimulate creativity.

- Ask students to draw a map of their empire on one side of the paper. As they work, ask the following questions. Take a fifteen to thirty-second break between questions, depending on their content.

- Where is the capital?

- Is the empire bordered by land or water? Is it an island or a continent?

- Are there any major geographical features? Mountains? Rivers?

- Are there rural areas? Urban areas? Uninhabited areas?

- Is the empire divided in any way?

- Ask students to turn their paper over and divide the page into four sections. Ask students to label the first section “Technology” and decide on a technology level for their worlds (low/medium/high). Then ask students to jot down notes answering the following questions:

- What are the roads made of?

- What are the buildings and homes made of?

- How do people travel?

- How do people across the empire communicate with one another?

- What do they eat?

- How do they cook?

- What weapons do they use?

- Ask students to label the second section “Magic” and decide on a magic level for their world (low/medium/high). Then ask students to jot down notes answering the following questions:

- Is magic common or uncommon?

- Who has the powers? Is magic relegated to humans, animals, or the natural world?

- Can magic be manipulated for human needs, or is it an objective, impartial force?

- Is it accepted or ostracized?

- Is it a tool for those in power?

- Are there more magical items or magical beings?

- How is magic “passed down” or transferred? Is it genetic or otherwise inherited? Is it tied to land, location, or life?

- How was magic used in your realm, historically?

- Is there a cost to using magic?

- Ask students to label the third section “Creatures” and decide on a population density of creatures in their empire (extinct/endangered/stable/overpopulation). Then ask students to jot down notes answering the following questions:

- Are the creatures domesticated or wild?

- Do they pose a threat to humans?

- Are they hunted or protected?

- Are they magical or mundane?

- Do humans use them?

- For transportation?

- For food?

- For protection?

- For magic?

- In the final section, ask students to name their hero?

- How old is your protagonist?

- What part of the empire are they from?

- Do they have a family?

- Do they have any use of magic? Are they entirely human?

- Have they suffered any hardships? Are they recent or long ago? Inherited or witnessed?

- Do they have any special skills?

- What is their weakness?

- Do they have a close friend or ally? Animal or human? Magical or mundane?

- Do they have an existing rival? Is this rivalry personal or cultural?

- What is their central conflict (Man vs. Man, Man vs. Nature, Man vs. World, Man vs. Gods, Man vs. Self)?

- Ask students to turn the page back over and name their empire. This is done at the end so that students may use their established details to better inform the connotation of their chosen name.

- Finally, ask students to draw a map of their Hero’s Journey throughout the empire. This should take about ten minutes. If omitting the Joseph Campbell portion of this exercise, professors may use whichever plot structure they have introduced in earlier classes or may use this as an opportunity to teach the stages of a narrative arc. Ask students to label, on the map, where each of the following events might occur, thinking about what scenes might unfold to align with each step.

- At this point, depending on each class’s desired goals, the professor may choose any of the following options:

- Discussion. Ask for student volunteers to share their empires and Heroes’ Journeys. Open the discussion by asking the following questions:

- Which details of your empire most helped guide your Hero’s Journey?

- Did you reference any popular, published works while creating your empire?

- What effect did the magical elements have on your protagonist and plot decisions? What freedom did they give you?

- Scene Work. Give students five to ten minutes to write. Ask them to choose the step in their Hero’s Journey that is speaking to them most clearly and begin a scene.

- Creative Extension. Ask students to write a short legend, myth, or fairytale popular within their empire. Instruct students to think about what these stories signify about a specific setting’s culture, values, and ideology.

- Further Development. To expand this exercise, ask students to take home their developed maps and complete a full narrative outline with a synopsis for each step in their Hero’s Journey, detailing scenes that would take place. Students may also include short character bios.

- Discussion. Ask for student volunteers to share their empires and Heroes’ Journeys. Open the discussion by asking the following questions:

Example of the Exercise

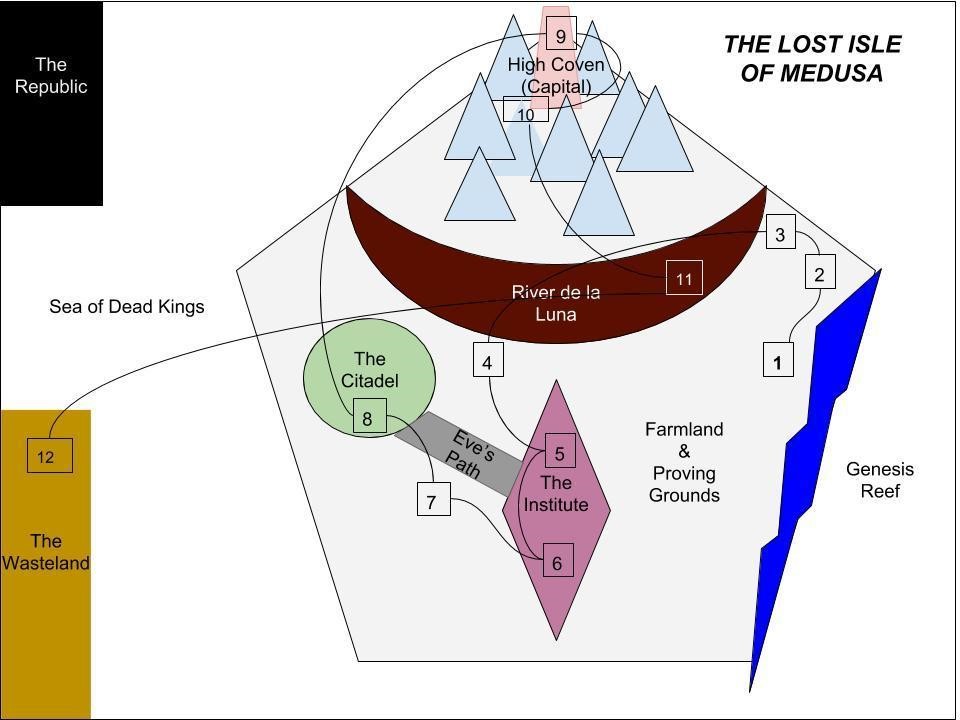

- Ordinary World—Freya is gathering seaweed and driftwood near Genesis Reef.

- Call to Adventure—A woman washes ashore with skin much darker than Freya’s green.

- Refusal of the Call—The woman begs Freya to swim back to the Wasteland with her, claiming other women are still there. Freya says that it is impossible because there have been no women there since they went into the sea and came to the Lost Isle.

- Meeting the Mentor—The woman and Freya struggle. She falls into the red river and meets Yi, a Medusa that lives solely underwater. During the ordeal, Yi helps Freya and the madwoman reach High Coven by finally leaving the water.

- Crossing the Threshold—Freya is finally summoned to the Institute to begin her magical training.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies—She meets Joan and Antoinette. She is jealous of the woman who sculpts water. She fails to find her magical ability.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave—On a field trip to the Citadel, they take Eve’s Path and find a woman like the one who first asked for Freya’s help. Freya convinces the others to bring the woman to the Citadel. The two bond on the remaining journey.

- Ordeal—Freya must escape Enforcers at the Citadel and traverse mountains with the woman until they reach the High Coven.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword)—Freya and the madwoman (Sylvya) admit their affection for one another.

- The Road Back—Freya learns of the growing Theman threat and the true history of the Lost Isle.

- Resurrection—Freya is baptized into the Coven’s Exploratory Force in the Red River.

- Return with the Elixir—Freya arrives at the Wasteland, searching for those still under the persecution of Themans.

Technology Level: Medium

|

Creatures: Stable Population

● Creatures are wild but work alongside the more “human” residents. ● There are legends of times when the creatures and humans were at war. A violent faction, called Themans, kept both the creatures and the life-giving sect of the population living in constant fear, mandating what each did with their own bodies. One night, the creatures carried everyone who was not a Theman into the sea. Not all survived, but when the creatures surfaced, those fated to return to nature remained. They were the first residents of the Lost Isle. Without the creatures or the life-givers to abuse, the populations of Themans turned their violence inward and dwindled down to angry pockets within the Republic. The former Greatest Empire was reduced to a wasteland. Ever since, the creatures and those who wash up on the Isle have coexisted peacefully. Each group protects and helps the other. ● The creatures are as magical as the surrounding world. They help the Medusas with transportation, gathering of greens in sea and high in trees, protection from the elements, and the channeling of universal forces. |

| Magic Level: High

● Magic is common, tied to the powers of the universe. ● Magic is an open force, permeating all those who are tethered to the universal pulse. Themans rarely have magical abilities and use weapons instead. ● Those with magical abilities can be manipulated by others for evil purposes, but the magic does not work if the user is aware of the intentions. The user must believe they are doing what is right, but that is often subjective. ● Magic is a source of jealousy and can be manipulated by those in power. ● Items cannot be magical unless a creation of nature. ● Magic has been used to protect the Lost Isle, making it appear invisible to searching Themans. ● The cost of magic is universal energy. This can take many forms: intentional tithes, sacrifices, accidental transfers.

|

Hero: Freya

|

Biography

Claire Agnes is a Pushcart-nominated writer of fiction and memoir originally from West Chester, Pennsylvania, and the daughter of a veterinarian and a blacksmith. She was the recipient of the 2015 Rowan Award for Women Writers, winner of the 2018 Adrift Short Story Contest, and a finalist in Narrative‘s 2019 Under 30 Contest. Her writing has been published or is forthcoming in Entropy, From the Fifth Floor, No Tokens, and Driftwood Press. She has spent time as a writer-in-residence at Stone Court, a Global Research Fellow in Prague, and a shaman’s apprentice in Iquitos. She serves as curator for the KGB Emerging Writers Reading Series in Manhattan, is a reader for Pigeon Pages, and is assistant fiction editor for Washington Square Review. She lives in Brooklyn, where she pursues her passions as a dedicated cat mom, occasional drag king, MFA candidate, and professor of creative writing at New York University.