Stairway to Hell

Andrew Gretes

Among writers, plot is a four-letter word. Perhaps the reason for this antagonism is that plot can be seen as restrictive or formulaic. With this line of thinking, plotting becomes the act of forcing something organic or dynamic into a cookie-cutter mold. The purpose of this lesson is to reinvigorate our conception of plot.

I encourage my students to see plot as a container that promotes creativity. When exploring this lesson, I often ask my students to consider haikus. What makes haikus wonderful and challenging is that they must bottle their poem within the container of five syllables, seven syllables, and five syllables. Likewise, with Zen calligraphy, the artist is given one brushstroke. Once the artist lifts their brush off the canvas, the artwork is complete. The question now becomes, what can you do with one brushstroke? It’s precisely this limit that allows for creativity. Like any good container, a plot holds a narrative together; it keeps the narrative from spilling, leaking, and slopping all over the place. Or, to use a different metaphor, the plot, like a spine, is what allows a story to stand, bend, twist, do somersaults, and perform other impressive narrative acrobatics.

The Stairway to Hell is a plot based on escalation. Things go from bad to worse to egregious. Popular examples of this plot include movies like The Hangover or Meet the Parents. This kind of plot typically begins with a situation that is potentially unstable (e.g., a bachelor party in Las Vegas). Next, anything that can go wrong does go wrong (e.g., the bachelor party drinks too much; they black out; they can’t find the groom; Mike Tyson shows up). As the story escalates, the characters in the story are forced to respond and unfold or reveal themselves. I imagine we’ve all had this experience before: being confronted with a dire situation and suddenly learning who we really are. Situations find us out. This is bad for life but good for storytelling.

In engaging with this lesson, students will (1) learn how to harness the potential of their own stories using a plot template I’ve titled “The Stairway to Hell”; (2) practice identifying the moves of this plot using George Saunders’s story “Sea Oak”; and (3) begin to structure and activate their own narratives using this template.

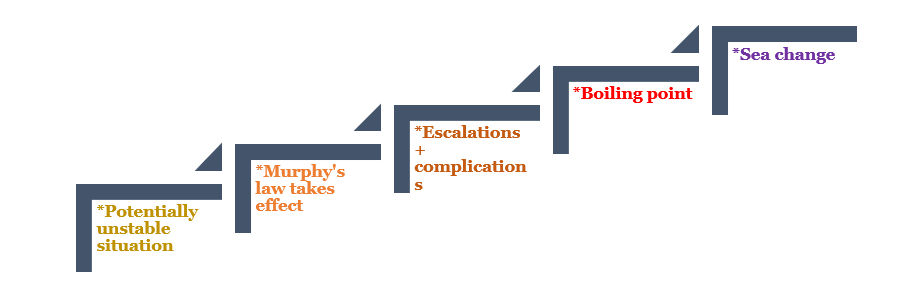

I’ve included a generic template for instructors to use (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Stairway to Hell Template

Step-by-Step Instructions

The following instructions include a suggested script to be delivered directly to the students.

- To students: In the Stairway to Hell model, the author is taking a potentially flammable situation and periodically dousing it with gasoline. The goal of each new scene is to make the flame a little bigger, hotter, or brighter.

However, if you simply put your characters through a jungle gym of terrible events, that’s not going to automatically create a good story. A good story needs more than that. It needs heart. It needs psychological complexity. So, each time you escalate the story, you’re also trying to complicate your characters. Put differently, escalation equals complication. Imagine your characters are circular in shape. With each new scene, your characters should grow and become more unique, harder to pin down, harder to summarize in one line. Ideally, your characters should enter the story with a circumference the size of a penny but end the story with a circumference the size of the sun.

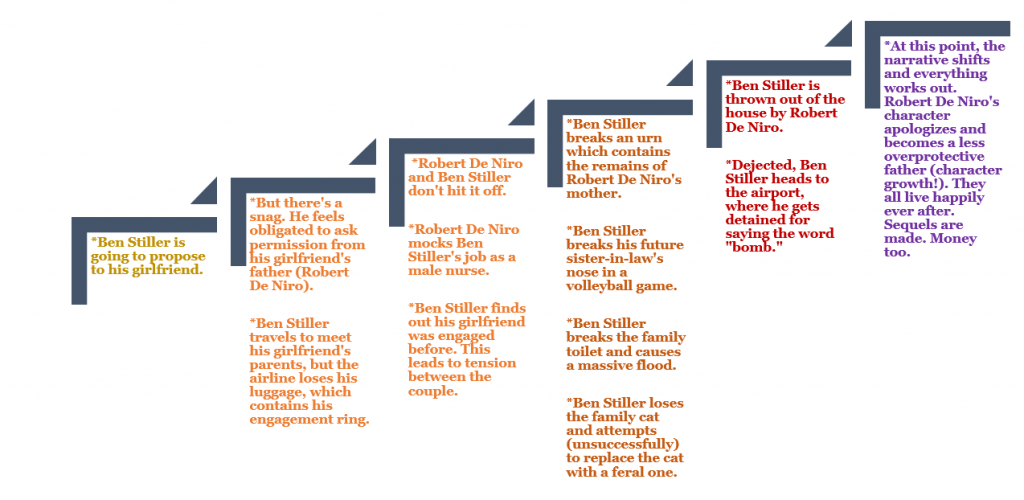

Let’s look at a fleshed-out example of this plot in the popular comedy Meet the Parents. In the movie, Ben Stiller’s character attempts to make a good impression with his future in-laws, but this attempt quickly goes downhill, until Stiller’s character is eventually kicked out of the house and leaves in disgrace (Figure 2).

Now, let’s try to apply this plot structure to George Saunders’s “Sea Oak.”

- Split the students into groups of two to four people and ask them to spend fifteen to twenty minutes filling in the Stairway to Hell template to the best of their ability.

- To students: Go back to the story and look at the individual scenes. Ask yourself the following questions: How is this scene furthering the story? How does this scene add new tensions and complications to the characters? What situation or dilemma is being doused with gasoline in this scene? Lastly, go back to the story and see if it makes a turn at the end: toward either a breaking point (a point of no return) or a point of redemption and possible grace.

- To students: Lastly, let’s apply this plot structure to your own fiction. Use the next ten minutes to write on the following prompt:

Choose a character…

- A teenager, recently diagnosed with diabetes, who joins a Brazilian jiu-jitsu class in order to regain control over her body

- A retired astronaut, mid-divorce, who is nostalgic about his NASA days and who wishes desperately to return to space

- Someone of your own devising

Now, pile trouble onto this character. Thwart their hopes and goals with problems, complications, and dilemmas. Put them into a frying pan and then dump them into the fire. The goal is to bring your character to a breaking point, a turning point, a place in which they either fall to a new depth or land on a new ledge. Put differently, the goal is to complicate the character until they’re not the same person anymore, for better or worse.

Biography

Andrew Gretes is the author of How to Dispose of Dead Elephants (Sandstone Press, 2014). His fiction has appeared in Witness, Booth, Passages North, and other journals. He teaches first-year writing at American University and George Washington University.