22 Chapter 22: Action Potentials and Nervous Systems

Joshua Reid

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, students should be able to:

22.1 Describe the function of a typical neuron and how its form contributes to this.

22.2 Describe the events of an action potential and be able to differntiate between depolarization and hyperpolarization.

22.3 Differentiate between inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters and their function on different body systems.

Nervous system

When you’re reading this book, your nervous system is performing several functions simultaneously. The visual system is processing what is seen on the page; the motor system controls the turn of the pages (or click of the mouse); the prefrontal cortex maintains attention. Even fundamental functions, like breathing and regulation of body temperature, are controlled by the nervous system. A nervous system is an organism’s control center: it processes sensory information from outside (and inside) the body and controls all behaviors—from eating to sleeping to finding a mate.

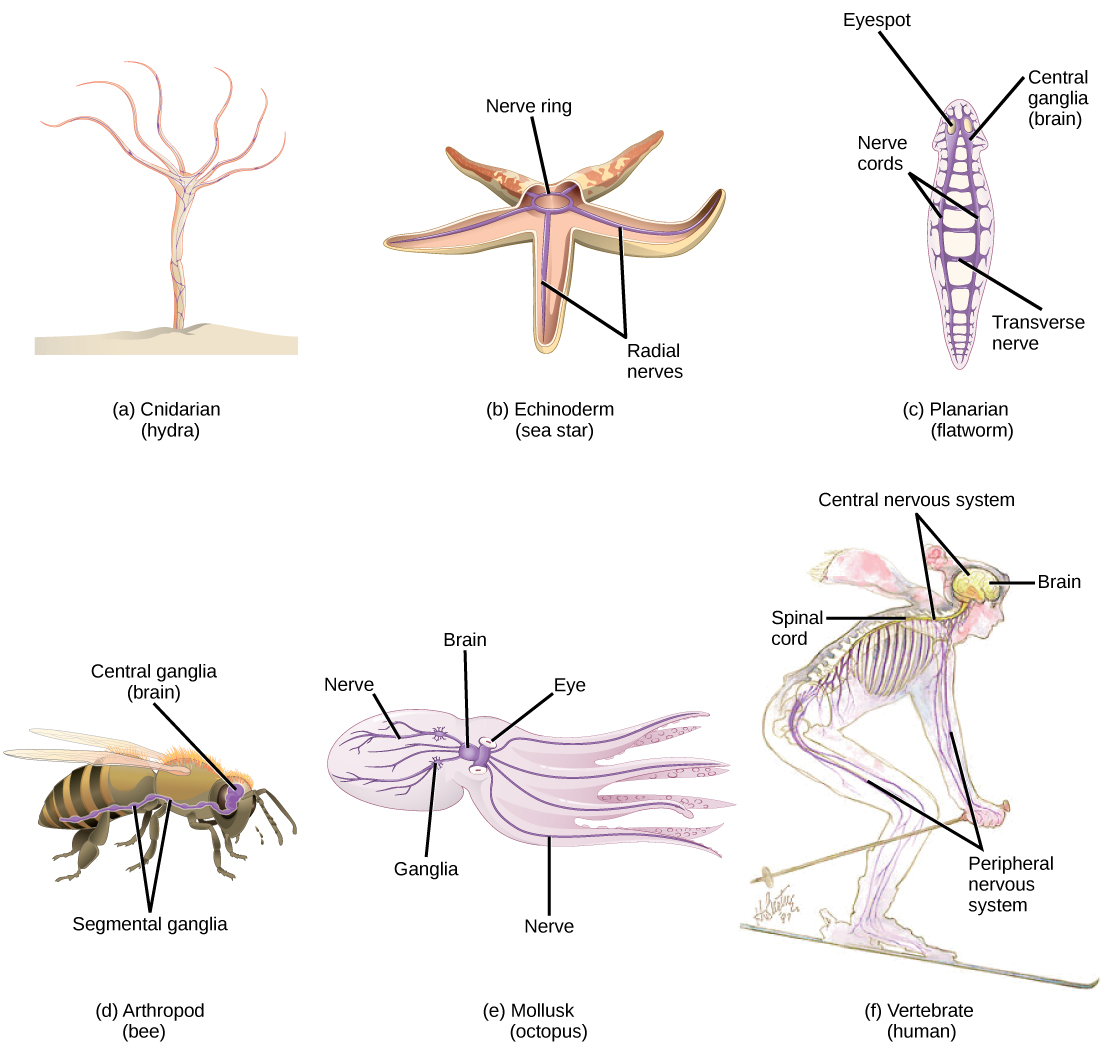

Nervous systems throughout the animal kingdom vary in structure and complexity. Some organisms, like sea sponges, lack a true nervous system. Others, like jellyfish, lack a true brain and instead have a system of separate but connected nerve cells (neurons) called a “nerve net.” Echinoderms such as sea stars have nerve cells that are bundled into fibers called nerves. Flatworms of the phylum Platyhelminthes have both a central nervous system (CNS), made up of a small “brain” and two nerve cords, and a peripheral nervous system (PNS) containing a system of nerves that extend throughout the body. The insect nervous system is more complex but also fairly decentralized. It contains a brain, ventral nerve cord, and ganglia (clusters of connected neurons). These ganglia can control movements and behaviors without input from the brain. Octopi may have the most complicated of invertebrate nervous systems—they have neurons that are organized in specialized lobes and eyes that are structurally similar to vertebrate species.

Compared to invertebrates, vertebrate nervous systems are more complex, centralized, and specialized. While there is great diversity among different vertebrate nervous systems, they all share a basic structure: a CNS that contains a brain and spinal cord and a PNS made up of peripheral sensory and motor nerves. One interesting difference between the nervous systems of invertebrates and vertebrates is that the nerve cords of many invertebrates are located ventrally whereas the vertebrate spinal cords are located dorsally. There is debate among evolutionary biologists as to whether these different nervous system plans evolved separately or whether the invertebrate body plan arrangement somehow “flipped” during the evolution of vertebrates.

Link to Learning

Watch this video of biologist Mark Kirschner discussing the “flipping” phenomenon of vertebrate evolution.

Reading Question #1

Which of the following statement(s) correctly describes invertebrate vs. vertebrae nervous systems?

A. In vertebrates, spinal cords are found on the ventral surface while in invertebrates, spinal cords are found on the dorsal surface.

B. Both types of organisms have a central and peripheral nervous system.

C. Invertebrate nervous systems tend to be more complex and specialized.

D. Invertebrate organisms don’t have neurons, while vertebrate organisms do.

The nervous system is made up of neurons, specialized cells that can receive and transmit chemical or electrical signals, and glia, cells that provide support functions for the neurons by playing an information processing role that is complementary to neurons. A neuron can be compared to an electrical wire—it transmits a signal from one place to another. Glia can be compared to the workers at the electric company who make sure wires go to the right places, maintain the wires, and take down wires that are broken. Although glia have been compared to workers, recent evidence suggests that they also usurp some of the signaling functions of neurons.

There is great diversity in the types of neurons and glia that are present in different parts of the nervous system. There are four major types of neurons, and they share several important cellular components.

Neurons

The nervous system of the common laboratory fly, Drosophila melanogaster, contains around 100,000 neurons, the same number as a lobster. This number compares to 75 million in the mouse and 300 million in the octopus. A human brain contains around 86 billion neurons. Despite these very different numbers, the nervous systems of these animals control many of the same behaviors—from basic reflexes to more complicated behaviors like finding food and courting mates. The ability of neurons to communicate with each other as well as with other types of cells underlies all of these behaviors.

Most neurons share the same cellular components. But neurons are also highly specialized—different types of neurons have different sizes and shapes that relate to their functional roles.

Parts of a Neuron

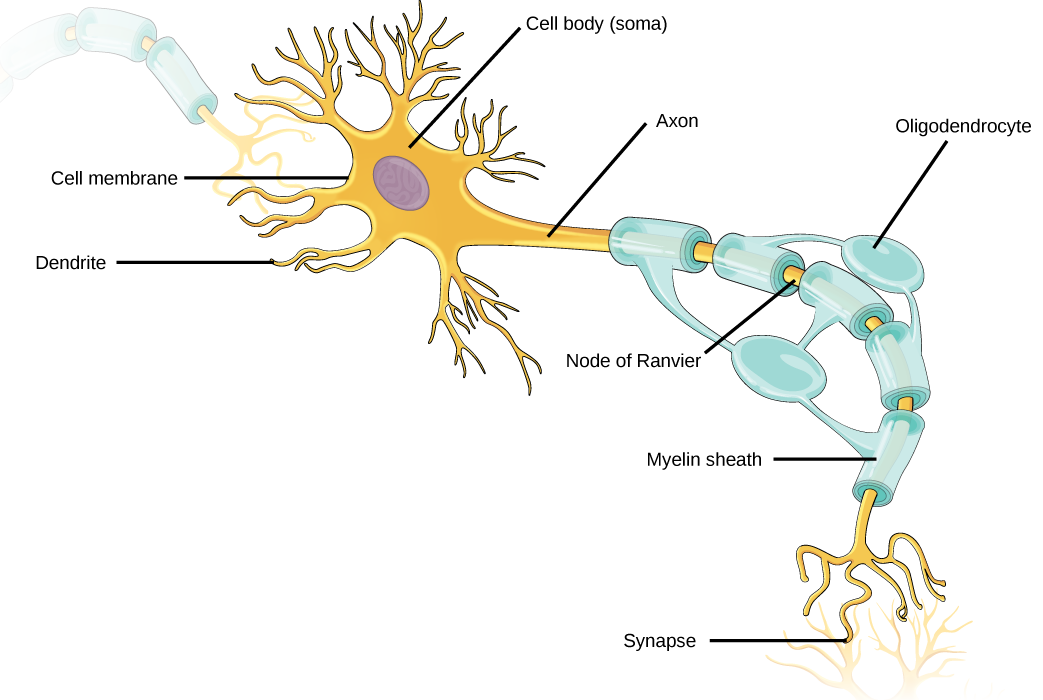

Like other cells, each neuron has a cell body (or soma) that contains a nucleus, smooth and rough endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, and other cellular components. Neurons also contain unique structures, illustrated in Figure 20.2 for receiving and sending the electrical signals that make neuronal communication possible. Dendrites are tree-like structures that extend away from the cell body to receive messages from other neurons at specialized junctions called synapses. Although some neurons do not have any dendrites, some types of neurons have multiple dendrites. Dendrites can have small protrusions called dendritic spines, which further increase surface area for possible synaptic connections.

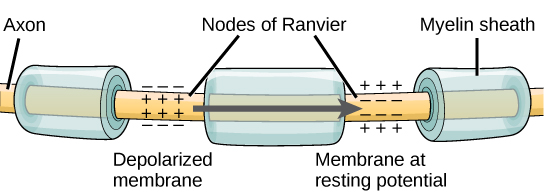

Once a signal is received by the dendrite, it then travels passively to the cell body. The cell body contains a specialized structure, the axon hillock that integrates signals from multiple synapses and serves as a junction between the cell body and an axon. An axon is a tube-like structure that propagates the integrated signal to specialized endings called axon terminals. These terminals in turn synapse on other neurons, muscle, or target organs. Chemicals released at axon terminals allow signals to be communicated to these other cells. Neurons usually have one or two axons, but some neurons, like amacrine cells in the retina, do not contain any axons. Some axons are covered with myelin, which acts as an insulator to minimize dissipation of the electrical signal as it travels down the axon, greatly increasing the speed of conduction. This insulation is important as the axon from a human motor neuron can be as long as a meter—from the base of the spine to the toes. The myelin sheath is not actually part of the neuron. Myelin is produced by glial cells. Along the axon there are periodic gaps in the myelin sheath. These gaps are called nodes of Ranvier and are sites where the signal is “recharged” as it travels along the axon.

It is important to note that a single neuron does not act alone—neuronal communication depends on the connections that neurons make with one another (as well as with other cells, like muscle cells). Dendrites from a single neuron may receive synaptic contact from many other neurons. For example, dendrites from a Purkinje cell in the cerebellum are thought to receive contact from as many as 200,000 other neurons.

Types of Neurons

There are different types of neurons, and the functional role of a given neuron is intimately dependent on its structure. There is an amazing diversity of neuron shapes and sizes found in different parts of the nervous system(and across species), as illustrated by the neurons shown in Figure 20.3.

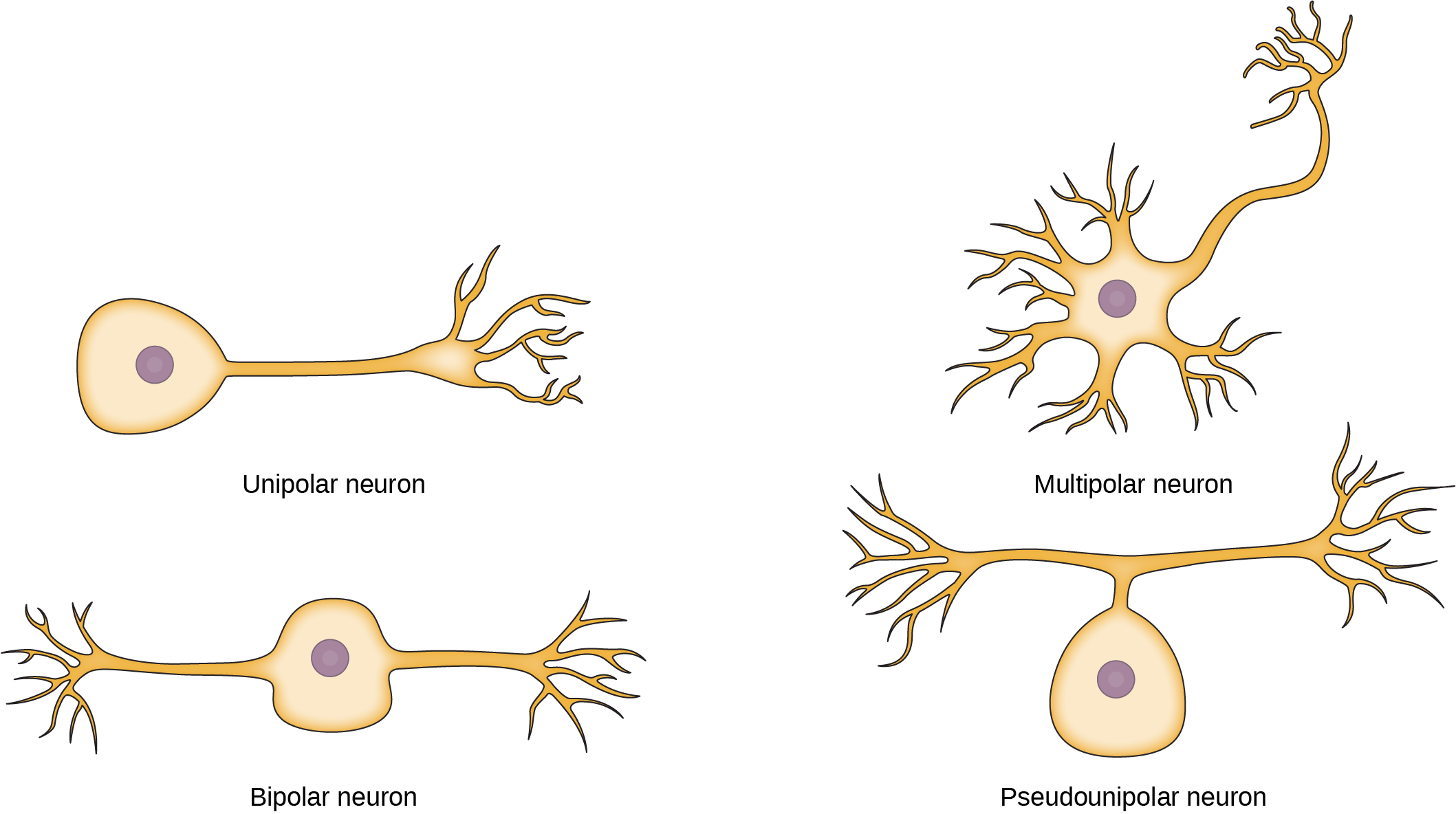

While there are many defined neuron cell subtypes, neurons are broadly divided into four basic types: unipolar, bipolar, multipolar, and pseudounipolar. Figure 20.4 illustrates these four basic neuron types. Unipolar neurons have only one structure that extends away from the soma. These neurons are not found in vertebrates but are found in insects where they stimulate muscles or glands. A bipolar neuron has one axon and one dendrite extending from the soma. An example of a bipolar neuron is a retinal bipolar cell, which receives signals from photoreceptor cells that are sensitive to light and transmits these signals to ganglion cells that carry the signal to the brain. Multipolar neurons are the most common type of neuron. Each multipolar neuron contains one axon and multiple dendrites. Multipolar neurons can be found in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). An example of a multipolar neuron is a Purkinje cell in the cerebellum, which has many branching dendrites but only one axon. Pseudounipolar cells share characteristics with both unipolar and bipolar cells. A pseudounipolar cell has a single process that extends from the soma, like a unipolar cell, but this process later branches into two distinct structures, like a bipolar cell. Most sensory neurons are pseudounipolar and have an axon that branches into two extensions: one connected to dendrites that receive sensory information and another that transmits this information to the spinal cord.

Everyday Connection

Neurogenesis

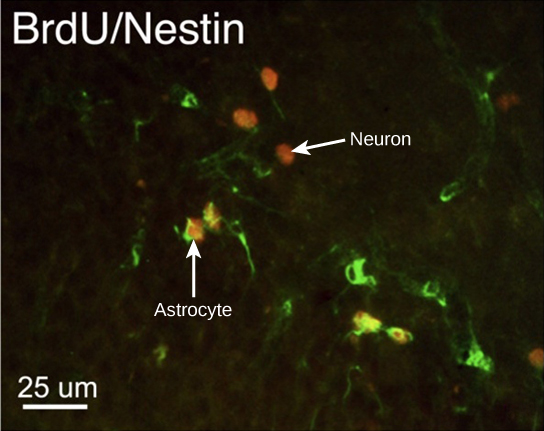

At one time, scientists believed that people were born with all the neurons they would ever have. Research performed during the last few decades indicates that neurogenesis, the birth of new neurons, continues into adulthood. Neurogenesis was first discovered in songbirds that produce new neurons while learning songs. For mammals, new neurons also play an important role in learning: about 1000 new neurons develop in the hippocampus (a brain structure involved in learning and memory) each day. While most of the new neurons will die, researchers found that an increase in the number of surviving new neurons in the hippocampus correlated with how well rats learned a new task. Interestingly, both exercise and some antidepressant medications also promote neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Stress has the opposite effect. While neurogenesis is quite limited compared to regeneration in other tissues, research in this area may lead to new treatments for disorders such as Alzheimer’s, stroke, and epilepsy.

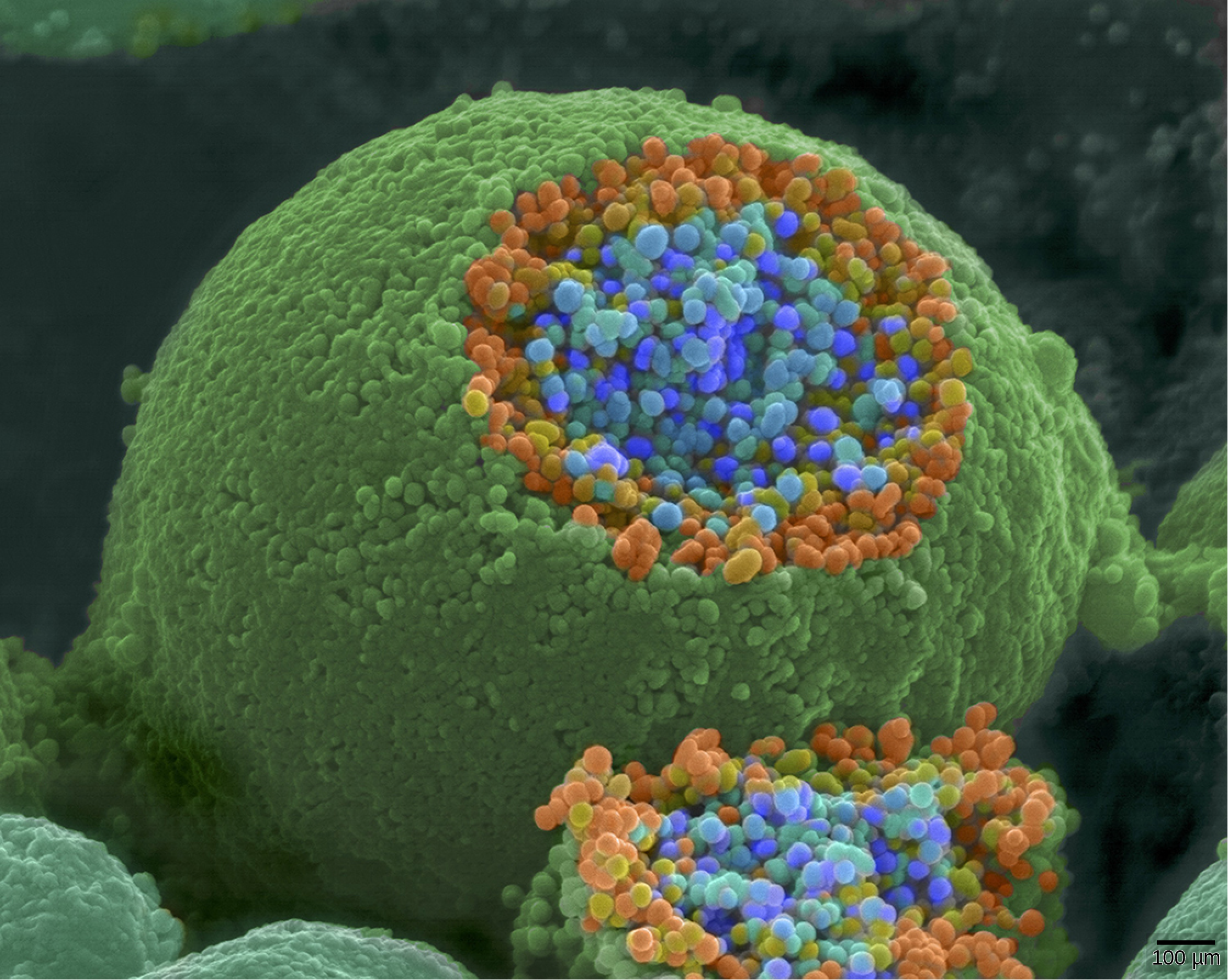

How do scientists identify new neurons? A researcher can inject a compound called bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) into the brain of an animal. While all cells will be exposed to BrdU, BrdU will only be incorporated into the DNA of newly generated cells that are in S phase. A technique called immunohistochemistry can be used to attach a fluorescent label to the incorporated BrdU, and a researcher can use fluorescent microscopy to visualize the presence of BrdU, and thus new neurons, in brain tissue. Figure 20.6 is a micrograph which shows fluorescently labeled neurons in the hippocampus of a rat.

Link to Learning

This site contains more information about neurogenesis, including an interactive laboratory simulation and a video that explains how BrdU labels new cells.

Reading Question #2

Which neuronal structure is responsible for releasing chemicals (e.g., neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin)?

A. Dendrite

B. Axon

C. Axon terminal

D. Soma

Reading Question #3

Which of the following statement(s) about neurogenesis is inaccurate?

A. Neurogenesis is defined as the process of formation of new neurons.

B. The main brain area in which neurogenesis has been observed is the amygdala.

C. The first organism in which neurogenesis was discovered was mice.

D. Both stress and exercise have a negative effect on neurogenesis.

E. New neurons are identified using immunohistochemistry.

Glia

While glia are often thought of as the supporting cast of the nervous system, the number of glial cells in the brain actually outnumbers the number of neurons by a factor of ten. Neurons would be unable to function without the vital roles that are fulfilled by these glial cells. Glia guide developing neurons to their destinations, buffer ions and chemicals that would otherwise harm neurons, and provide myelin sheaths around axons. Scientists have recently discovered that they also play a role in responding to nerve activity and modulating communication between nerve cells. When glia do not function properly, the result can be disastrous—most brain tumors are caused by mutations in glia.

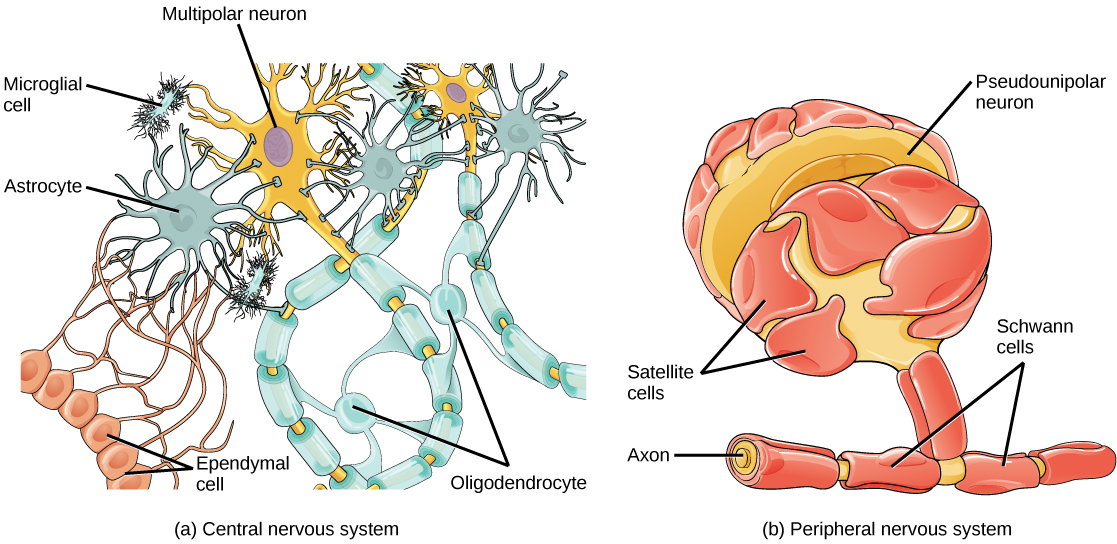

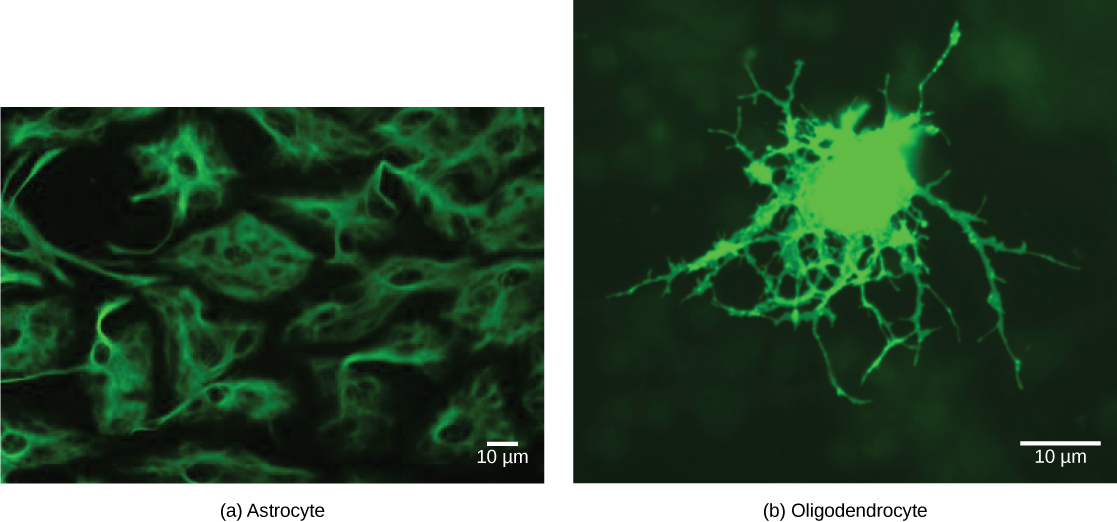

Types of Glia

There are several different types of glia with different functions, two of which are shown in Figure 20.7. Astrocytes, shown in Figure 20.8a make contact with both capillaries and neurons in the CNS. They provide nutrients and other substances to neurons, regulate the concentrations of ions and chemicals in the extracellular fluid, and provide structural support for synapses. Astrocytes also form the blood-brain barrier—a structure that blocks entrance of toxic substances into the brain. Astrocytes, in particular, have been shown through calcium imaging experiments to become active in response to nerve activity, transmit calcium waves between astrocytes, and modulate the activity of surrounding synapses. Satellite glia provide nutrients and structural support for neurons in the PNS. Microgliascavenge and degrade dead cells and protect the brain from invading microorganisms. Oligodendrocytes, shown in Figure 20.8b form myelin sheaths around axons in the CNS. One axon can be myelinated by several oligodendrocytes, and one oligodendrocyte can provide myelin for multiple neurons. This is distinctive from the PNS where a single Schwann cell provides myelin for only one axon as the entire Schwann cell surrounds the axon. Radial glia serve as scaffolds for developing neurons as they migrate to their end destinations. Ependymalcells line fluid-filled ventricles of the brain and the central canal of the spinal cord. They are involved in the production of cerebrospinal fluid, which serves as a cushion for the brain, moves the fluid between the spinal cord and the brain, and is a component for the choroid plexus.

All functions performed by the nervous system—from a simple motor reflex to more advanced functions like making a memory or a decision—require neurons to communicate with one another. While humans use words and body language to communicate, neurons use electrical and chemical signals. Just like a person in a committee, one neuron usually receives and synthesizes messages from multiple other neurons before “making the decision” to send the message on to other neurons.

Nerve Impulse Transmission within a Neuron

For the nervous system to function, neurons must be able to send and receive signals. These signals are possible because each neuron has a charged cellular membrane (a voltage difference between the inside and the outside), and the charge of this membrane can change in response to neurotransmitter molecules released from other neurons and environmental stimuli. To understand how neurons communicate, one must first understand the basis of the baseline or ‘resting’ membrane charge.

Neuronal Charged Membranes

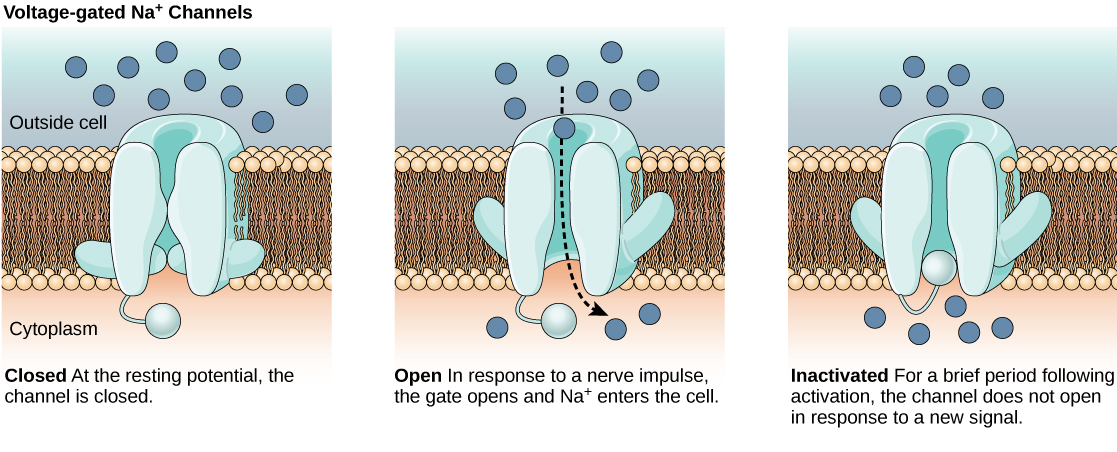

The lipid bilayer membrane that surrounds a neuron is impermeable to charged molecules or ions. To enter or exit the neuron, ions must pass through special proteins called ion channels that span the membrane. Ion channels have different configurations: open, closed, and inactive, as illustrated in Figure 20.9. Some ion channels need to be activated in order to open and allow ions to pass into or out of the cell. These ion channels are sensitive to the environment and can change their shape accordingly. Ion channels that change their structure in response to voltage changes are called voltage-gated ion channels. Voltage-gated ion channels regulate the relative concentrations of different ions inside and outside the cell. The difference in total charge between the inside and outside of the cell is called the membrane potential.

Link to Learning

This video discusses the basis of the resting membrane potential.

Resting Membrane Potential

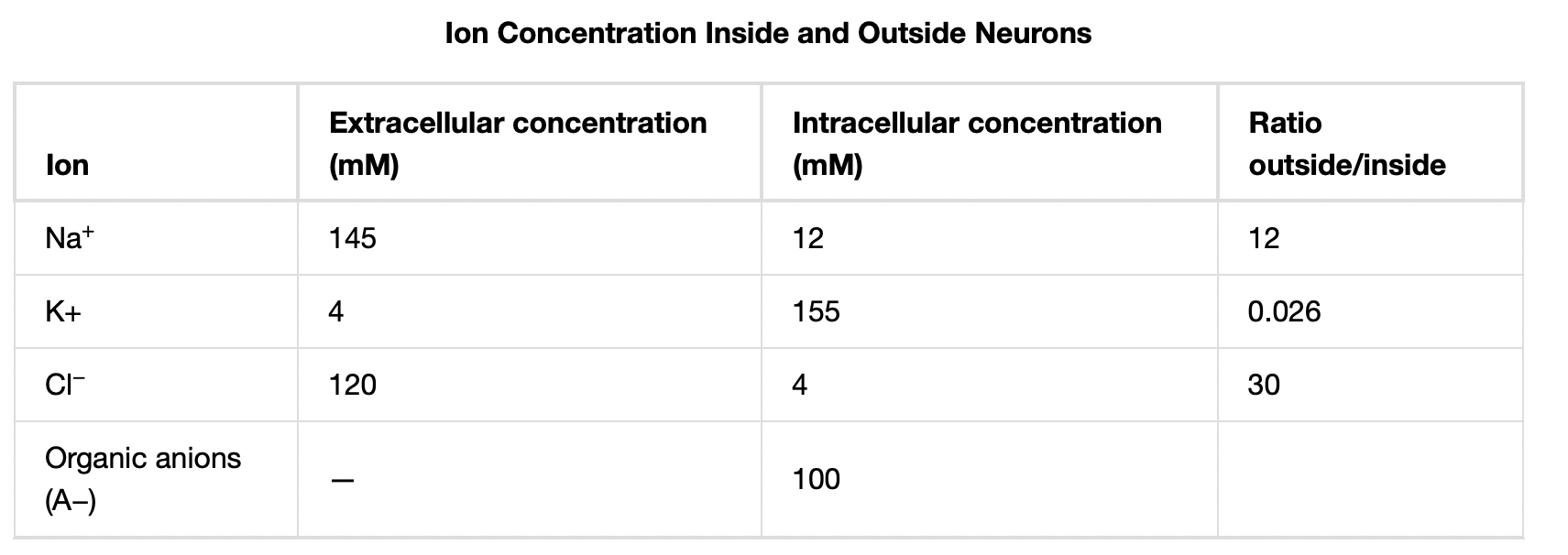

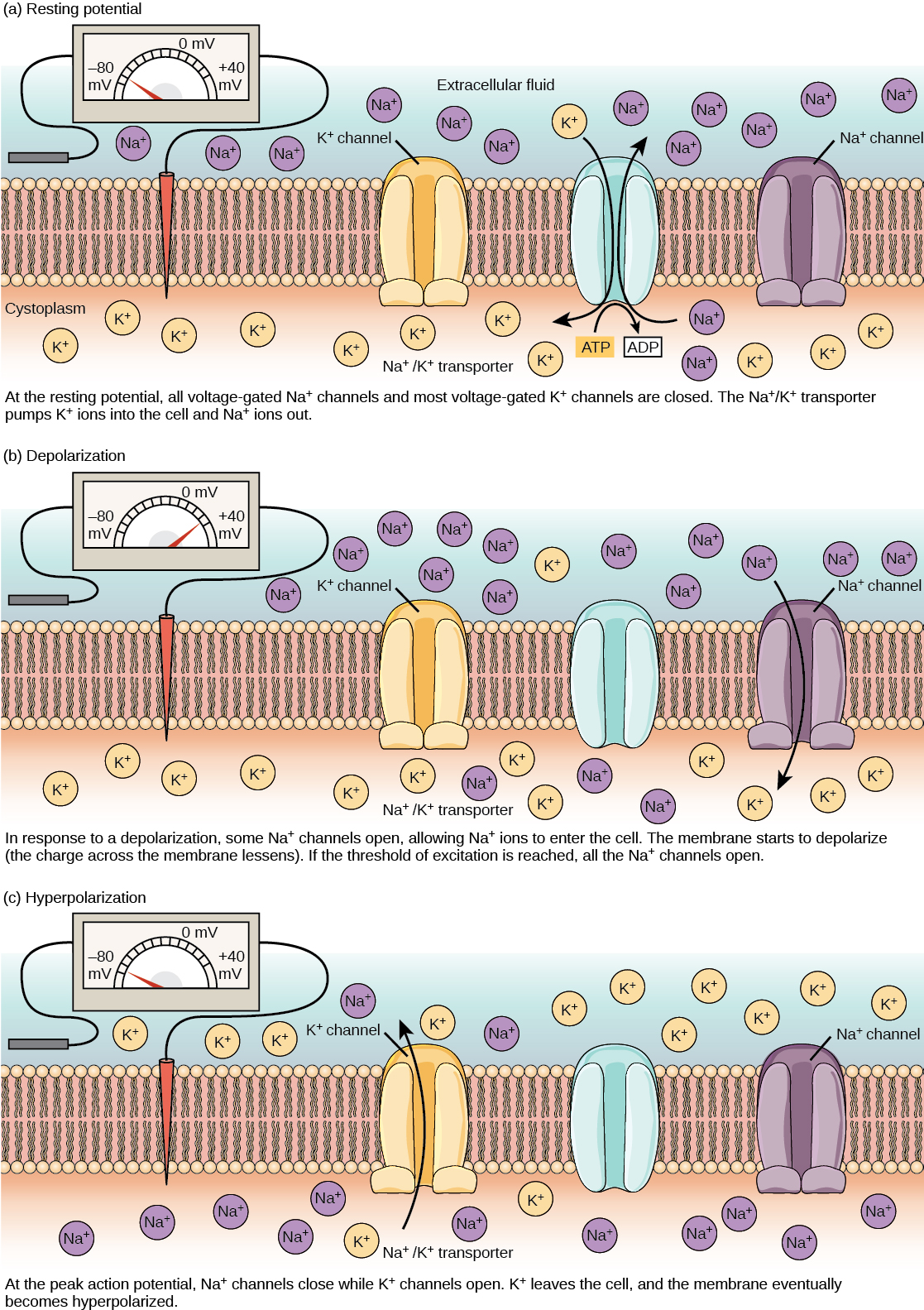

A neuron at rest is negatively charged: the inside of a cell is approximately 70 millivolts more negative than the outside (−70 mV, note that this number varies by neuron type and by species). This voltage is called the resting membrane potential; it is caused by differences in the concentrations of ions inside and outside the cell. If the membrane were equally permeable to all ions, each type of ion would flow across the membrane and the system would reach equilibrium. Because ions cannot simply cross the membrane at will, there are different concentrations of several ions inside and outside the cell, as shown in Table 20.1. The difference in the number of positively charged potassium ions (K+) inside and outside the cell dominates the resting membrane potential (Figure 20.10). When the membrane is at rest, K+ ions accumulate inside the cell due to the activity of the Na/K pump, driving both ions against their concentration gradient. The negative resting membrane potential is created and maintained by increasing the concentration of cations outside the cell (in the extracellular fluid) relative to inside the cell (in the cytoplasm). The negative charge within the cell is created by the cell membrane being more permeable to potassium ion movement than sodium ion movement. In neurons, potassium ions are maintained at high concentrations within the cell while sodium ions are maintained at high concentrations outside of the cell. The cell possesses potassium and sodium leakage channels that allow the two cations to diffuse down their concentration gradient. However, the neurons have far more potassium leakage channels than sodium leakage channels. Therefore, potassium diffuses out of the cell at a much faster rate than sodium leaks in. Because more cations are leaving the cell than are entering, this causes the interior of the cell to be negatively charged relative to the outside of the cell. The actions of the sodium potassium pump help to maintain the resting potential, once established. Recall that sodium potassium pumps brings two K+ ions into the cell while removing three Na+ ions per ATP consumed. As more cations are expelled from the cell than taken in, the inside of the cell remains negatively charged relative to the extracellular fluid. It should be noted that chloride ions (Cl–) tend to accumulate outside of the cell because they are repelled by negatively-charged proteins within the cytoplasm.

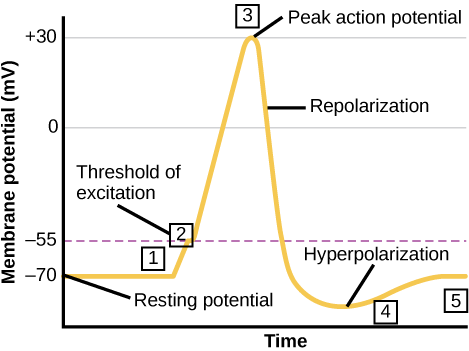

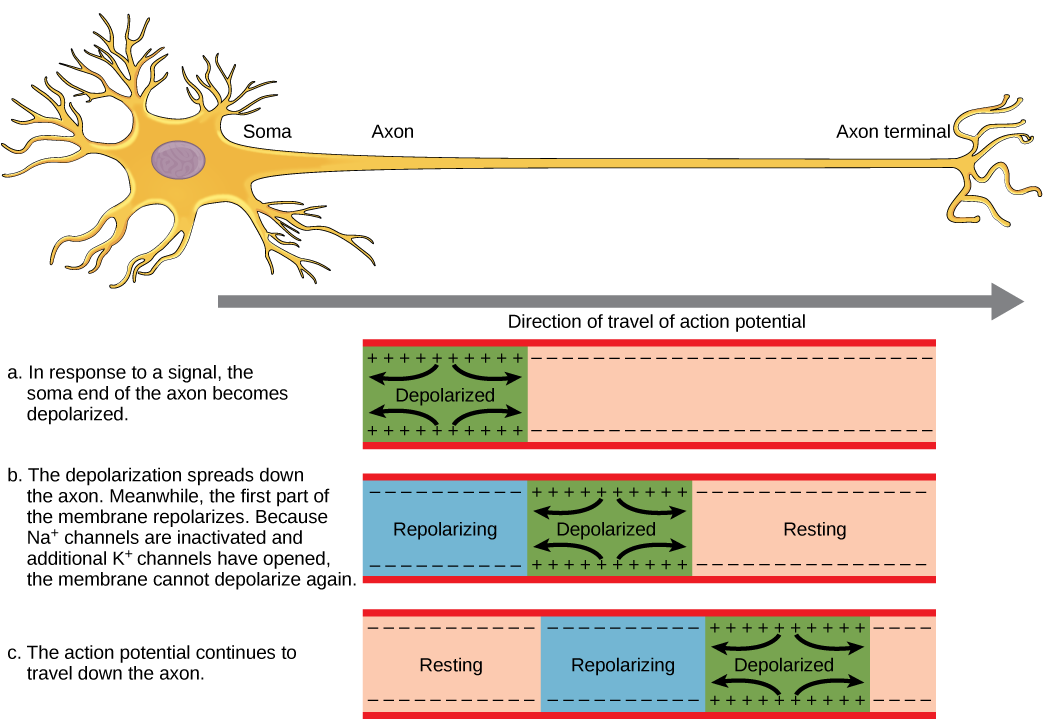

Action Potential

A neuron can receive input from other neurons and, if this input is strong enough, send the signal to downstream neurons. Transmission of a signal between neurons is generally carried by a chemical called a neurotransmitter. Transmission of a signal within a neuron (from dendrite to axon terminal) is carried by a brief reversal of the resting membrane potential called an action potential. When neurotransmitter molecules bind to receptors located on a neuron’s dendrites, ion channels open. At excitatory synapses, this opening allows positive ions to enter the neuron and results in depolarization of the membrane—a decrease in the difference in voltage between the inside and outside of the neuron. A stimulus from a sensory cell or another neuron depolarizes the target neuron to its threshold potential (-55 mV). Na+ channels in the axon hillock open, allowing positive ions to enter the cell (Figure 20.10 and Figure 20.11). Once the sodium channels open, the neuron completely depolarizes to a membrane potential of about +40 mV. Action potentials are considered an “all-or nothing” event, in that, once the threshold potential is reached, the neuron always completely depolarizes. Once depolarization is complete, the cell must now “reset” its membrane voltage back to the resting potential. To accomplish this, the Na+ channels close and cannot be opened. This begins the neuron’s refractory period, in which it cannot produce another action potential because its sodium channels will not open. At the same time, voltage-gated K+ channels open, allowing K+ to leave the cell. As K+ ions leave the cell, the membrane potential once again becomes negative and repolarizes. The diffusion of K+ out of the cell actually continues for a short period of time past the time of the achievement of the resting potential, and the membrane hyperpolarizes, in that the membrane potential becomes more negative than the cell’s normal resting potential. This is the result of the slow closing of the K+ channels. At this point, the sodium channels will return to their resting state, meaning they are ready to open again if the membrane potential again exceeds the threshold potential. Eventually all the K+ channels close, and the cell returns back to its resting membrane potential.

Link to Learning

This video presents an overview of action potential.

Reading Question #4

Rank the order of the events in an action potential.

A) The cell repolarizes, wherein Na+ channels close and K+ channels open, resulting in K+ efflux.

B) The cell depolarizes, wherein Na+ channels open because of a stimulus, resulting in Na+ influx.

C) The cell hyperpolarizes due to continued K+ efflux.

D) The cell is at its resting potential of -70 mV.

Myelin and the Propagation of the Action Potential

For an action potential to communicate information to another neuron, it must travel along the axon and reach the axon terminals where it can initiate neurotransmitter release. The speed of conduction of an action potential along an axon is influenced by both the diameter of the axon and the axon’s resistance to current leak. Myelin acts as an insulator that prevents current from leaving the axon; this increases the speed of action potential conduction. In demyelinating diseases like multiple sclerosis, action potential conduction slows because current leaks from previously insulated axon areas. The nodes of Ranvier, illustrated in Figure 20.13 are gaps in the myelin sheath along the axon. These unmyelinated spaces are about one micrometer long and contain voltage-gated Na+ and K+channels. Flow of ions through these channels, particularly the Na+ channels, regenerates the action potential over and over again along the axon. This ‘jumping’ of the action potential from one node to the next is called saltatory conduction. If nodes of Ranvier were not present along an axon, the action potential would propagate very slowly since Na+ and K+ channels would have to continuously regenerate action potentials at every point along the axon instead of at specific points. Nodes of Ranvier also save energy for the neuron since the channels only need to be present at the nodes and not along the entire axon.

Synaptic Transmission

The synapse or “gap” is the place where information is transmitted from one neuron to another. Synapses usually form between axon terminals and dendritic spines, but this is not universally true. There are also axon-to-axon, dendrite-to-dendrite, and axon-to-cell body synapses. The neuron transmitting the signal is called the presynaptic neuron, and the neuron receiving the signal is called the postsynaptic neuron. Note that these designations are relative to a particular synapse—most neurons are both presynaptic and postsynaptic. There are two types of synapses: chemical and electrical.

Chemical Synapse

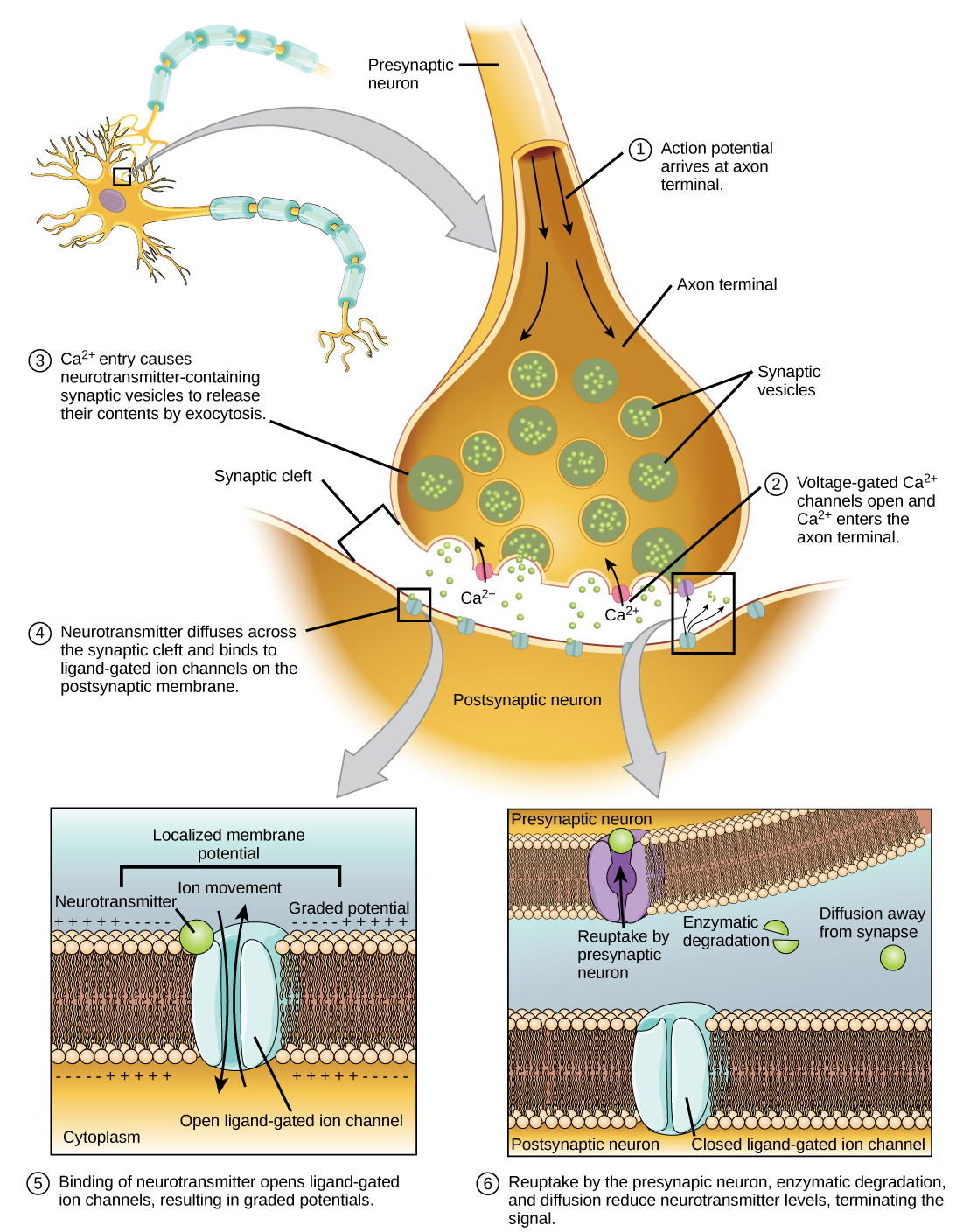

When an action potential reaches the axon terminal it depolarizes the membrane and opens voltage-gated Na+channels. Na+ ions enter the cell, further depolarizing the presynaptic membrane. This depolarization causes voltage-gated Ca2+ channels to open. Calcium ions entering the cell initiate a signaling cascade that causes small membrane-bound vesicles, called synaptic vesicles, containing neurotransmitter molecules to fuse with the presynaptic membrane. Synaptic vesicles are shown in Figure 20.14, which is an image from a scanning electron microscope.

Fusion of a vesicle with the presynaptic membrane causes neurotransmitter to be released into the synaptic cleft, the extracellular space between the presynaptic and postsynaptic membranes, as illustrated in Figure 20.15. The neurotransmitter diffuses across the synaptic cleft and binds to receptor proteins on the postsynaptic membrane.

The binding of a specific neurotransmitter causes particular ion channels, in this case ligand-gated channels, on the postsynaptic membrane to open. Neurotransmitters can either have excitatory or inhibitory effects on the postsynaptic membrane. For example, when acetylcholine is released at the synapse between a nerve and muscle (called the neuromuscular junction) by a presynaptic neuron, it causes postsynaptic Na+ channels to open. Na+enters the postsynaptic cell and causes the postsynaptic membrane to depolarize. This depolarization is called an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) and makes the postsynaptic neuron more likely to fire an action potential. Release of neurotransmitter at inhibitory synapses causes inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs), a hyperpolarization of the presynaptic membrane. For example, when the neurotransmitter GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) is released from a presynaptic neuron, it binds to and opens Cl– channels. Cl– ions enter the cell and hyperpolarizes the membrane, making the neuron less likely to fire an action potential.

Once neurotransmission has occurred, the neurotransmitter must be removed from the synaptic cleft so the postsynaptic membrane can “reset” and be ready to receive another signal. This can be accomplished in three ways: the neurotransmitter can diffuse away from the synaptic cleft, it can be degraded by enzymes in the synaptic cleft, or it can be recycled (sometimes called reuptake) by the presynaptic neuron. Several drugs act at this step of neurotransmission. For example, some drugs that are given to Alzheimer’s patients work by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase, the enzyme that degrades acetylcholine. This inhibition of the enzyme essentially increases neurotransmission at synapses that release acetylcholine. Once released, the acetylcholine stays in the cleft and can continually bind and unbind to postsynaptic receptors.

Electrical Synapse

While electrical synapses are fewer in number than chemical synapses, they are found in all nervous systems and play important and unique roles. The mode of neurotransmission in electrical synapses is quite different from that in chemical synapses. In an electrical synapse, the presynaptic and postsynaptic membranes are very close together and are actually physically connected by channel proteins forming gap junctions. Gap junctions allow current to pass directly from one cell to the next. In addition to the ions that carry this current, other molecules, such as ATP, can diffuse through the large gap junction pores.

There are key differences between chemical and electrical synapses. Because chemical synapses depend on the release of neurotransmitter molecules from synaptic vesicles to pass on their signal, there is an approximately one millisecond delay between when the axon potential reaches the presynaptic terminal and when the neurotransmitter leads to opening of postsynaptic ion channels. Additionally, this signaling is unidirectional. Signaling in electrical synapses, in contrast, is virtually instantaneous (which is important for synapses involved in key reflexes), and some electrical synapses are bidirectional. Electrical synapses are also more reliable as they are less likely to be blocked, and they are important for synchronizing the electrical activity of a group of neurons. For example, electrical synapses in the thalamus are thought to regulate slow-wave sleep, and disruption of these synapses can cause seizures.

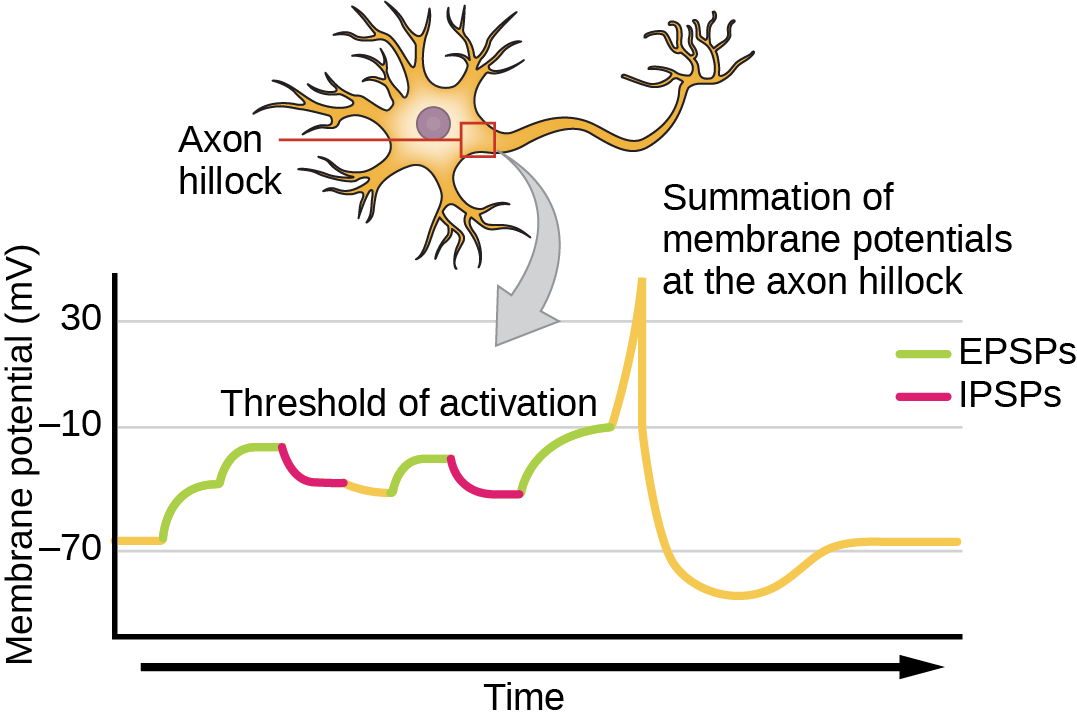

Signal Summation

Sometimes a single EPSP is strong enough to induce an action potential in the postsynaptic neuron, but often multiple presynaptic inputs must create EPSPs around the same time for the postsynaptic neuron to be sufficiently depolarized to fire an action potential. This process is called summation and occurs at the axon hillock, as illustrated in Figure 20.16. Additionally, one neuron often has inputs from many presynaptic neurons—some excitatory and some inhibitory—so IPSPs can cancel out EPSPs and vice versa. It is the net change in postsynaptic membrane voltage that determines whether the postsynaptic cell has reached its threshold of excitation needed to fire an action potential. Together, synaptic summation and the threshold for excitation act as a filter so that random “noise” in the system is not transmitted as important information.

Synaptic Plasticity

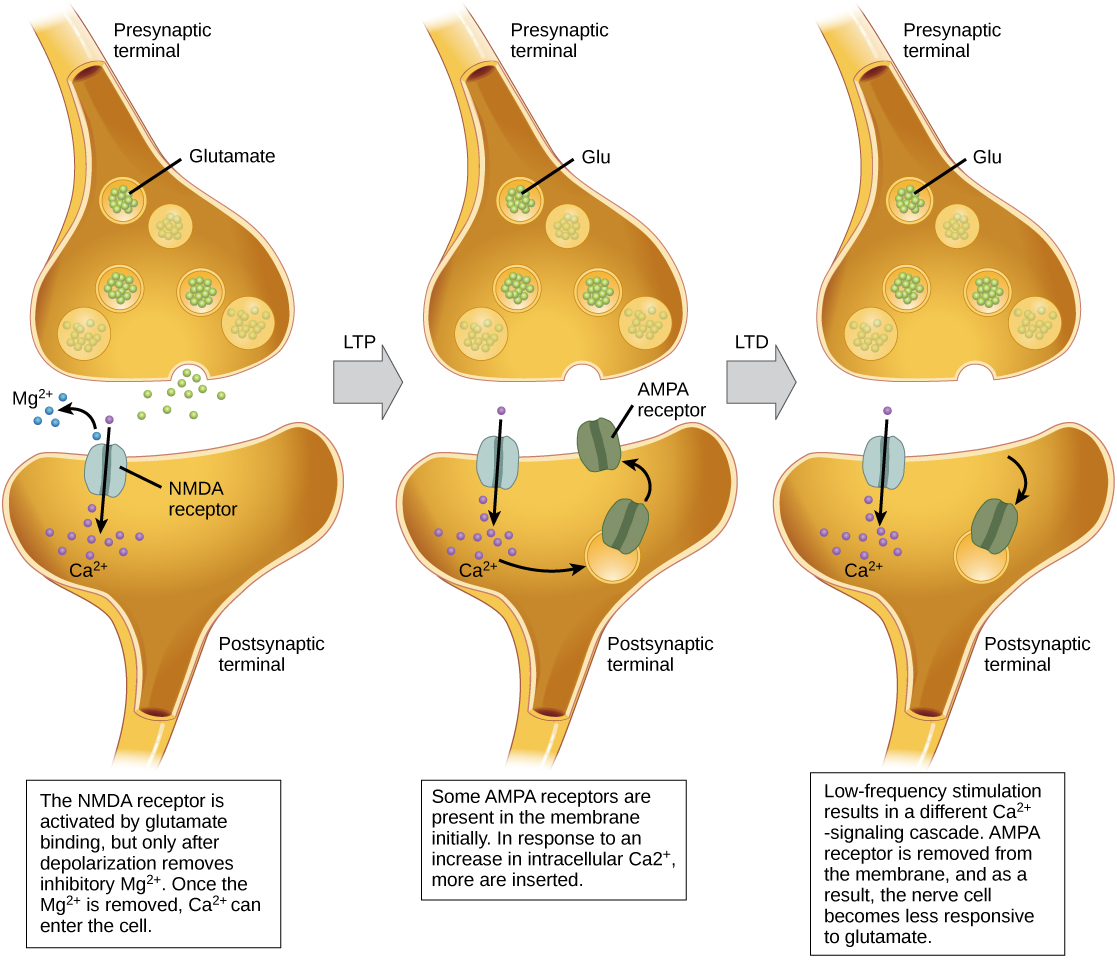

Synapses are not static structures. They can be weakened or strengthened. They can be broken, and new synapses can be made. Synaptic plasticity allows for these changes, which are all needed for a functioning nervous system. In fact, synaptic plasticity is the basis of learning and memory. Two processes in particular, long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) are important forms of synaptic plasticity that occur in synapses in the hippocampus, a brain region that is involved in storing memories.

Long-term Potentiation (LTP)

Long-term potentiation (LTP) is a persistent strengthening of a synaptic connection. LTP is based on the Hebbian principle: cells that fire together wire together. There are various mechanisms, none fully understood, behind the synaptic strengthening seen with LTP. One known mechanism involves a type of postsynaptic glutamate receptor, called NMDA (N-Methyl-D-aspartate) receptors, shown in Figure 20.18. These receptors are normally blocked by magnesium ions; however, when the postsynaptic neuron is depolarized by multiple presynaptic inputs in quick succession (either from one neuron or multiple neurons), the magnesium ions are forced out allowing calcium ions to pass into the postsynaptic cell. Next, Ca2+ ions entering the cell initiate a signaling cascade that causes a different type of glutamate receptor, called AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid) receptors, to be inserted into the postsynaptic membrane, since activated AMPA receptors allow positive ions to enter the cell. So, the next time glutamate is released from the presynaptic membrane, it will have a larger excitatory effect (EPSP) on the postsynaptic cell because the binding of glutamate to these AMPA receptors will allow more positive ions into the cell. The insertion of additional AMPA receptors strengthens the synapse and means that the postsynaptic neuron is more likely to fire in response to presynaptic neurotransmitter release. Some drugs of abuse co-opt the LTP pathway, and this synaptic strengthening can lead to addiction.

Long-term Depression (LTD)

Long-term depression (LTD) is essentially the reverse of LTP: it is a long-term weakening of a synaptic connection. One mechanism known to cause LTD also involves AMPA receptors. In this situation, calcium that enters through NMDA receptors initiates a different signaling cascade, which results in the removal of AMPA receptors from the postsynaptic membrane, as illustrated in Figure 20.18. The decrease in AMPA receptors in the membrane makes the postsynaptic neuron less responsive to glutamate released from the presynaptic neuron. While it may seem counterintuitive, LTD may be just as important for learning and memory as LTP. The weakening and pruning of unused synapses allows for unimportant connections to be lost and makes the synapses that have undergone LTP that much stronger by comparison.

Reading Question #5

Caffeine inhibits the action of adenosine (an inhibitory neurotransmitter). Therefore, caffeine is referred to as a

A. Stimulant

B. Depressant

C. Inhibitory neurotransmitter

D. Excitatory neurotransmitter

References

Adapted from Clark, M.A., Douglas, M., and Choi, J. (2018). Biology 2e. OpenStax. Retrieved from https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/35-introduction?query=nervous%20system&target=%7B%22index%22%3A0%2C%22type%22%3A%22search%22%7D#fig-ch35_00_01