12.5 International Entry Modes

After reading this section, students should be able to …

- describe the five common international-expansion entry modes.

- know the advantages and disadvantages of each entry mode.

- understand the dynamics among the choice of different entry modes.

12.5.1 The Five Common International-Expansion Entry Modes

What is the best way to enter a new market? Should a company first establish an export base or license its products to gain experience in a newly targeted country or region? Or does the potential associated with first-mover status justify a bolder move such as entering an alliance, making an acquisition, or even starting a new subsidiary? Many companies move from exporting to licensing to a higher investment strategy, in effect treating these choices as a learning curve. Each has distinct advantages and disadvantages. In this section, we will explore the traditional international-expansion entry modes. Beyond importing, international expansion is achieved through exporting, licensing arrangements, partnering and strategic alliances, acquisitions, and establishing new, wholly owned subsidiaries, also known as greenfield ventures. These modes of entering international markets and their characteristics are shown in Table 7.1 “International-Expansion Entry Modes”.1 Each mode of market entry has advantages and disadvantages. Firms need to evaluate their options to choose the entry mode that best suits their strategy and goals.

Table 12.1 International-Expansion Entry Modes

| Type of Entry | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Exporting | Fast entry, low risk | Low control, low local knowledge, potential negative environmental impact of transportation |

| Licensing and Franchising | Fast entry, low cost, low risk | Less control, licensee may become a competitor, legal and regulatory environment (IP and contract law) must be sound |

| Partnering and Strategic Alliance | Shared costs reduce investment needed, reduced risk, seen as local entity | Higher cost than exporting, licensing, or franchising; integration problems between two corporate cultures |

| Acquisition | Fast entry; known, established operations | High cost, integration issues with home office |

| Greenfield Venture (Launch of a new, wholly owned subsidiary) | Gain local market knowledge; can be seen as insider who employs locals; maximum control | High cost, high risk due to unknowns, slow entry due to setup time |

Exporting

Exporting is the marketing and direct sale of domestically produced goods in another country. Exporting is a traditional and well-established method of reaching foreign markets. Since it does not require that the goods be produced in the target country, no investment in foreign production facilities is required. Most of the costs associated with exporting take the form of marketing expenses.

While relatively low risk, exporting entails substantial costs and limited control. Exporters typically have little control over the marketing and distribution of their products, face high transportation charges and possible tariffs, and must pay distributors for a variety of services. What is more, exporting does not give a company firsthand experience in staking out a competitive position abroad, and it makes it difficult to customize products and services to local tastes and preferences.

Exporting is a typically the easiest way to enter an international market, and therefore most firms begin their international expansion using this model of entry. Exporting is the sale of products and services in foreign countries that are sourced from the home country. The advantage of this mode of entry is that firms avoid the expense of establishing operations in the new country. Firms must, however, have a way to distribute and market their products in the new country, which they typically do through contractual agreements with a local company or distributor. When exporting, the firm must give thought to labeling, packaging, and pricing the offering appropriately for the market. In terms of marketing and promotion, the firm will need to let potential buyers know of its offerings, be it through advertising, trade shows, or a local sales force.

Amusing Anecdotes

One common factor in exporting is the need to translate something about a product or service into the language of the target country. This requirement may be driven by local regulations or by the company’s wish to market the product or service in a locally friendly fashion. While this may seem to be a simple task, it’s often a source of embarrassment for the company and humor for competitors. David Ricks’s book on international business blunders relates the following anecdote for US companies doing business in the neighboring French-speaking Canadian province of Quebec. A company boasted of lait frais usage, which translates to “used fresh milk,” when it meant to brag of lait frais employé, or “fresh milk used.” The “terrific” pens sold by another company were instead promoted as terrifiantes, or terrifying. In another example, a company intending to say that its appliance could use “any kind of electrical current,” actually stated that the appliance “wore out any kind of liquid.” And imagine how one company felt when its product to “reduce heartburn” was advertised as one that reduced “the warmth of heart”!2

Among the disadvantages of exporting are the costs of transporting goods to the country, which can be high and can have a negative impact on the environment. In addition, some countries impose tariffs on incoming goods, which will impact the firm’s profits. In addition, firms that market and distribute products through a contractual agreement have less control over those operations and, naturally, must pay their distribution partner a fee for those services.

Ethics in Action

Companies are starting to consider the environmental impact of where they locate their manufacturing facilities. For example, Olam International, a cashew producer, originally shipped nuts grown in Africa to Asia for processing. Now, however, Olam has opened processing plants in Tanzania, Mozambique, and Nigeria. These locations are close to where the nuts are grown. The result? Olam has lowered its processing and shipping costs by 25 percent while greatly reducing carbon emissions.3

Likewise, when Walmart enters a new market, it seeks to source produce for its food sections from local farms that are near its warehouses. Walmart has learned that the savings it gets from lower transportation costs and the benefit of being able to restock in smaller quantities more than offset the lower prices it was getting from industrial farms located farther away. This practice is also a win-win for locals, who have the opportunity to sell to Walmart, which can increase their profits and let them grow and hire more people and pay better wages. This, in turn, helps all the businesses in the local community.4

Firms export mostly to countries that are close to their facilities because of the lower transportation costs and the often greater similarity between geographic neighbors. For example, Mexico accounts for 40 percent of the goods exported from Texas.5 The Internet has also made exporting easier. Even small firms can access critical information about foreign markets, examine a target market, research the competition, and create lists of potential customers. Even applying for export and import licenses is becoming easier as more governments use the Internet to facilitate these processes.

Because the cost of exporting is lower than that of the other entry modes, entrepreneurs and small businesses are most likely to use exporting as a way to get their products into markets around the globe. Even with exporting, firms still face the challenges of currency exchange rates. While larger firms have specialists that manage the exchange rates, small businesses rarely have this expertise. One factor that has helped reduce the number of currencies that firms must deal with was the formation of the European Union (EU) and the move to a single currency, the euro, for the first time. As of 2011, seventeen of the twenty-seven EU members use the euro, giving businesses access to 331 million people with that single currency.6

Licensing and Franchising

A company that wants to get into an international market quickly while taking only limited financial and legal risks might consider licensing agreements with foreign companies. An international licensing agreement allows a foreign company (the licensee) to sell the products of a producer (the licensor) or to use its intellectual property (such as patents, trademarks, copyrights) in exchange for royalty fees. Here’s how it works: You own a company in the United States that sells coffee-flavored popcorn. You’re sure that your product would be a big hit in Japan, but you don’t have the resources to set up a factory or sales office in that country. You can’t make the popcorn here and ship it to Japan because it would get stale. So you enter into a licensing agreement with a Japanese company that allows your licensee to manufacture coffee-flavored popcorn using your special process and to sell it in Japan under your brand name. In exchange, the Japanese licensee would pay you a royalty fee.

Licensing essentially permits a company in the target country to use the property of the licensor. Such property is usually intangible, such as trademarks, patents, and production techniques. The licensee pays a fee in exchange for the rights to use the intangible property and possibly for technical assistance as well.

Because little investment on the part of the licensor is required, licensing has the potential to provide a very large return on investment. However, because the licensee produces and markets the product, potential returns from manufacturing and marketing activities may be lost. Thus, licensing reduces cost and involves limited risk. However, it does not mitigate the substantial disadvantages associated with operating from a distance. As a rule, licensing strategies inhibit control and produce only moderate returns.

Another popular way to expand overseas is to sell franchises. Under an international franchise agreement, a company (the franchiser) grants a foreign company (the franchisee) the right to use its brand name and to sell its products or services. The franchisee is responsible for all operations but agrees to operate according to a business model established by the franchiser. In turn, the franchiser usually provides advertising, training, and new-product assistance. Franchising is a natural form of global expansion for companies that operate domestically according to a franchise model, including restaurant chains, such as McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken, and hotel chains, such as Holiday Inn and Best Western.

Contract Manufacturing and Outsourcing

Because of high domestic labor costs, many U.S. companies manufacture their products in countries where labor costs are lower. This arrangement is called international contract manufacturing or outsourcing. A U.S. company might contract with a local company in a foreign country to manufacture one of its products. It will, however, retain control of product design and development and put its own label on the finished product. Contract manufacturing is quite common in the U.S. apparel business, with most American brands being made in a number of Asian countries, including China, Vietnam, Indonesia, and India.[4]

Thanks to twenty-first-century information technology, nonmanufacturing functions can also be outsourced to nations with lower labor costs. U.S. companies increasingly draw on a vast supply of relatively inexpensive skilled labor to perform various business services, such as software development, accounting, and claims processing. For years, American insurance companies have processed much of their claims-related paperwork in Ireland. With a large, well-educated population with English language skills, India has become a center for software development and customer-call centers for American companies. In the case of India, as you can see in Table 7.1 “Selected Hourly Wages, United States and India” , the attraction is not only a large pool of knowledge workers but also significantly lower wages.

Table 12.2 Selected Hourly Wages, United States and India

| Occupation | U.S. Wage per Hour (per year) | Indian Wage per Hour (per year) |

| Middle-level manager | $29.40 per hour ($60,000 per year) | $6.30 per hour ($13,000 per year) |

| Information technology specialist | $35.10 per hour ($72,000 per year) | $7.50 per hour ($15,000 per year) |

| Manual worker | $13.00 per hour ($27,000 per year) | $2.20 per hour ($5,000 per year) |

Source: Data obtained from “Huge Wage Gaps for the Same Work Between Countries – June 2011,” WageIndicator.com, http://www.wageindicator.org/main/WageIndicatorgazette/wageindicator-news/huge-wage-gaps-for-the-same-work-between-countries-June-2011 (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site.(accessed September 20, 2011).

Partnerships and Strategic Alliances

Another way to enter a new market is through a strategic alliance with a local partner. A strategic alliance involves a contractual agreement between two or more enterprises stipulating that the involved parties will cooperate in a certain way for a certain time to achieve a common purpose. To determine if the alliance approach is suitable for the firm, the firm must decide what value the partner could bring to the venture in terms of both tangible and intangible aspects. The advantages of partnering with a local firm are that the local firm likely understands the local culture, market, and ways of doing business better than an outside firm. Partners are especially valuable if they have a recognized, reputable brand name in the country or have existing relationships with customers that the firm might want to access. For example, Cisco formed a strategic alliance with Fujitsu to develop routers for Japan. In the alliance, Cisco decided to co-brand with the Fujitsu name so that it could leverage Fujitsu’s reputation in Japan for IT equipment and solutions while still retaining the Cisco name to benefit from Cisco’s global reputation for switches and routers.7 Similarly, Xerox launched signed strategic alliances to grow sales in emerging markets such as Central and Eastern Europe, India, and Brazil.8

Strategic alliances and joint ventures have become increasingly popular in recent years. They allow companies to share the risks and resources required to enter international markets. And although returns also may have to be shared, they give a company a degree of flexibility not afforded by going it alone through direct investment.

There are several motivations for companies to consider a partnership as they expand globally, including (a) facilitating market entry, (b) risk and reward sharing, (c) technology sharing, (d) joint product development, and (e) conforming to government regulations. Other benefits include political connections and distribution channel access that may depend on relationships.

Such alliances often are favorable when (a) the partners’ strategic goals converge while their competitive goals diverge; (b) the partners’ size, market power, and resources are small compared to the industry leaders; and (c) partners are able to learn from one another while limiting access to their own proprietary skills.

What if a company wants to do business in a foreign country but lacks the expertise or resources? Or what if the target nation’s government doesn’t allow foreign companies to operate within its borders unless it has a local partner? In these cases, a firm might enter into a strategic alliance with a local company or even with the government itself. A strategic alliance is an agreement between two companies (or a company and a nation) to pool resources in order to achieve business goals that benefit both partners. For example, Viacom (a leading global media company) has a strategic alliance with Beijing Television to produce Chinese-language music and entertainment programming.[5]

An alliance can serve a number of purposes:

- Enhancing marketing efforts

- Building sales and market share

- Improving products

- Reducing production and distribution costs

- Sharing technology

Alliances range in scope from informal cooperative agreements to joint ventures—alliances in which the partners fund a separate entity (perhaps a partnership or a corporation) to manage their joint operation. Magazine publisher Hearst, for example, has joint ventures with companies in several countries. So, young women in Israel can read Cosmo Israel in Hebrew, and Russian women can pick up a Russian-language version of Cosmo that meets their needs. The U.S. edition serves as a starting point to which nationally appropriate material is added in each different nation. This approach allows Hearst to sell the magazine in more than fifty countries.[6]

Strategic alliances are also advantageous for small entrepreneurial firms that may be too small to make the needed investments to enter the new market themselves. In addition, some countries require foreign-owned companies to partner with a local firm if they want to enter the market. For example, in Saudi Arabia, non-Saudi companies looking to do business in the country are required by law to have a Saudi partner. This requirement is common in many Middle Eastern countries. Even without this type of regulation, a local partner often helps foreign firms bridge the differences that otherwise make doing business locally impossible. Walmart, for example, failed several times over nearly a decade to effectively grow its business in Mexico, until it found a strong domestic partner with similar business values.

The disadvantages of partnering, on the other hand, are lack of direct control and the possibility that the partner’s goals differ from the firm’s goals. David Ricks, who has written a book on blunders in international business, describes the case of a US company eager to enter the Indian market: “It quickly negotiated terms and completed arrangements with its local partners. Certain required documents, however, such as the industrial license, foreign collaboration agreements, capital issues permit, import licenses for machinery and equipment, etc., were slow in being issued. Trying to expedite governmental approval of these items, the US firm agreed to accept a lower royalty fee than originally stipulated. Despite all of this extra effort, the project was not greatly expedited, and the lower royalty fee reduced the firm’s profit by approximately half a million dollars over the life of the agreement.”9 Failing to consider the values or reliability of a potential partner can be costly, if not disastrous.

To avoid these missteps, Cisco created one globally integrated team to oversee its alliances in emerging markets. Having a dedicated team allows Cisco to invest in training the managers how to manage the complex relationships involved in alliances. The team follows a consistent model, using and sharing best practices for the benefit of all its alliances.10

Did You Know?

Partnerships in emerging markets can be used for social good as well. For example, pharmaceutical company Novartis crafted multiple partnerships with suppliers and manufacturers to develop, test, and produce antimalaria medicine on a nonprofit basis. The partners included several Chinese suppliers and manufacturing partners as well as a farm in Kenya that grows the medication’s key raw ingredient. To date, the partnership, called the Novartis Malaria Initiative, has saved an estimated 750,000 lives through the delivery of 300 million doses of the medication.11

The key issues to consider in a joint venture are ownership, control, length of agreement, pricing, technology transfer, local firm capabilities and resources, and government intentions. Potential problems include (a) conflict over asymmetric new investments, (b) mistrust over proprietary knowledge, (c) performance ambiguity, that is, how to “split the pie,” (d) lack of parent firm support, (e) cultural clashes, and (f) if, how, and when to terminate the relationship.

Ultimately, most companies will aim at building their own presence through company-owned facilities in important international markets. Acquisitions or greenfield start-ups represent this ultimate commitment. Acquisition is faster, but starting a new, wholly owned subsidiary might be the preferred option if no suitable acquisition candidates can be found.

Acquisitions

An acquisition is a transaction in which a firm gains control of another firm by purchasing its stock, exchanging the stock for its own, or, in the case of a private firm, paying the owners a purchase price. In our increasingly flat world, cross-border acquisitions have risen dramatically. In recent years, cross-border acquisitions have made up over 60 percent of all acquisitions completed worldwide. Acquisitions are appealing because they give the company quick, established access to a new market. However, they are expensive, which in the past had put them out of reach as a strategy for companies in the undeveloped world to pursue. What has changed over the years is the strength of different currencies. The higher interest rates in developing nations has strengthened their currencies relative to the dollar or euro. If the acquiring firm is in a country with a strong currency, the acquisition is comparatively cheaper to make. As Wharton professor Lawrence G. Hrebiniak explains, “Mergers fail because people pay too much of a premium. If your currency is strong, you can get a bargain.”12

When deciding whether to pursue an acquisition strategy, firms examine the laws in the target country. China has many restrictions on foreign ownership, for example, but even a developed-world country like the United States has laws addressing acquisitions. For example, you must be an American citizen to own a TV station in the United States. Likewise, a foreign firm is not allowed to own more than 25 percent of a US airline.13

Acquisition is a good entry strategy to choose when scale is needed, which is particularly the case in certain industries (e.g., wireless telecommunications). Acquisition is also a good strategy when an industry is consolidating. Nonetheless, acquisitions are risky. Many studies have shown that between 40 percent and 60 percent of all acquisitions fail to increase the market value of the acquired company by more than the amount invested.14

Foreign Direct Investment and Subsidiaries

Many of the approaches to global expansion that we’ve discussed so far allow companies to participate in international markets without investing in foreign plants and facilities. As markets expand, however, a firm might decide to enhance its competitive advantage by making a direct investment in operations conducted in another country.

Also known as foreign direct investment (FDI), acquisitions and greenfield start-ups involve the direct ownership of facilities in the target country and, therefore, the transfer of resources including capital, technology, and personnel. Direct ownership provides a high degree of control in the operations and the ability to better know the consumers and competitive environment. However, it requires a high level of resources and a high degree of commitment.

Foreign direct investment refers to the formal establishment of business operations on foreign soil—the building of factories, sales offices, and distribution networks to serve local markets in a nation other than the company’s home country. On the other hand offshoring occurs when the facilities set up in the foreign country replace U.S. manufacturing facilities and are used to produce goods that will be sent back to the United States for sale. Shifting production to low-wage countries is often criticized as it results in the loss of jobs for U.S. workers.[7]

FDI is generally the most expensive commitment that a firm can make to an overseas market, and it’s typically driven by the size and attractiveness of the target market. For example, German and Japanese automakers, such as BMW, Mercedes, Toyota, and Honda, have made serious commitments to the U.S. market: most of the cars and trucks that they build in plants in the South and Midwest are destined for sale in the United States.

A common form of FDI is the foreign subsidiary: an independent company owned by a foreign firm (called the parent). This approach to going international not only gives the parent company full access to local markets but also exempts it from any laws or regulations that may hamper the activities of foreign firms. The parent company has tight control over the operations of a subsidiary, but while senior managers from the parent company often oversee operations, many managers and employees are citizens of the host country. Not surprisingly, most very large firms have foreign subsidiaries. IBM and Coca-Cola, for example, have both had success in the Japanese market through their foreign subsidiaries (IBM-Japan and Coca-Cola–Japan). FDI goes in the other direction, too, and many companies operating in the United States are in fact subsidiaries of foreign firms. Gerber Products, for example, is a subsidiary of the Swiss company Novartis, while Stop & Shop and Giant Food Stores belong to the Dutch company Royal Ahold.

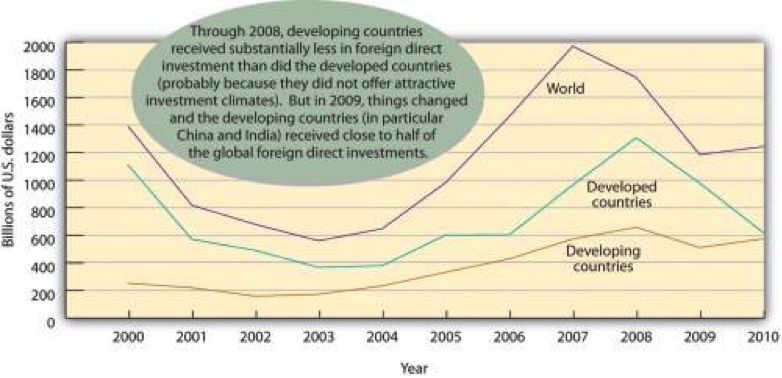

Where does most FDI capital end up? Figure 7.3 “Where FDI Goes” provides an overview of amounts, destinations (developed or developing countries), and trends.

All these strategies have been successful in the arena of global business. But success in international business involves more than merely finding the best way to reach international markets. Doing global business is a complex, risky endeavor. As many companies have learned the hard way, people and organizations don’t do things the same way abroad as they do at home. What differences make global business so tricky? That’s the question that we’ll turn to next.

Wholly Owned Subsidiaries

Firms may want to have a direct operating presence in the foreign country, completely under their control. To achieve this, the company can establish a new, wholly owned subsidiary (i.e., a greenfield venture) from scratch, or it can purchase an existing company in that country. Some companies purchase their resellers or early partners (as Vitrac Egypt did when it bought out the shares that its partner, Vitrac, owned in the equity joint venture). Other companies may purchase a local supplier for direct control of the supply. This is known as vertical integration.

Establishing or purchasing a wholly owned subsidiary requires the highest commitment on the part of the international firm, because the firm must assume all of the risk—financial, currency, economic, and political.

The process of establishing of a new, wholly owned subsidiary is often complex and potentially costly, but it affords the firm maximum control and has the most potential to provide above-average returns. The costs and risks are high given the costs of establishing a new business operation in a new country. The firm may have to acquire the knowledge and expertise of the existing market by hiring either host-country nationals—possibly from competitive firms—or costly consultants. An advantage is that the firm retains control of all its operations.

Did You Know: McDonald’s International

McDonald’s has a plant in Italy that supplies all the buns for McDonald’s restaurants in Italy, Greece, and Malta. International sales has accounted for as much as 60 percent of McDonald’s annual revenue.15

12.5.2 Cautions When Purchasing an Existing Foreign Enterprise

As we’ve seen, some companies opt to purchase an existing company in the foreign country outright as a way to get into a foreign market quickly. When making an acquisition, due diligence is important—not only on the financial side but also on the side of the country’s culture and business practices. The annual disposable income in Russia, for example, exceeds that of all the other BRIC countries (i.e., Brazil, India, and China). For many major companies, Russia is too big and too rich to ignore as a market. However, Russia also has a reputation for corruption and red tape that even its highest-ranking officials admit. In a BusinessWeek article, presidential economic advisor Arkady Dvorkovich (whose office in the Kremlin was once occupied by Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev), for example, advises, “Investors should choose wisely” which regions of Russia they locate their business in, warning that some areas are more corrupt than others. Corruption makes the world less flat precisely because it undermines the viability of legal vehicles, such as licensing, which otherwise lead to a flatter world.

The culture of corruption is even embedded into some Russian company structures. In the 1990s, laws inadvertently encouraged Russian firms to establish legal headquarters in offshore tax havens, like Cyprus. A tax haven is a country that has very advantageous (low) corporate income taxes.

Businesses registered in these offshore tax havens to avoid certain Russian taxes. Even though companies could obtain a refund on these taxes from the Russian government, “the procedure is so complicated you never actually get a refund,” said Andrey Pozdnyakov, cofounder of Siberian-based Elecard, in the same BusinessWeek article.

This offshore registration, unfortunately, is a danger sign to potential investors like Intel. “We can’t invest in companies that have even a slight shadow,” said Intel’s Moscow-based regional director Dmitry Konash about the complex structure predicament. 16

Did You Know: Business Collaborations in China

Some foreign companies believe that owning their own operations in China is an easier option than having to deal with a Chinese partner. For example, many foreign companies still fear that their Chinese partners will learn too much from them and become competitors. However, in most cases, the Chinese partner knows the local culture—both that of the customers and workers—and is better equipped to deal with Chinese bureaucracy and regulations. In addition, even wholly owned subsidiaries can’t be totally independent of Chinese firms, on whom they might have to rely for raw materials and shipping as well as maintenance of government contracts and distribution channels.

Collaborations offer different kinds of opportunities and challenges than self-handling Chinese operations. For most companies, the local nuances of the Chinese market make some form of collaboration desirable. The companies that opt to self-handle their Chinese operations tend to be very large and/or have a proprietary technology base, such as high-tech or aerospace companies—for example, Boeing or Microsoft. Even then, these companies tend to hire senior Chinese managers and consultants to facilitate their market entry and then help manage their expansion. Nevertheless, navigating the local Chinese bureaucracy is tough, even for the most-experienced companies.

Let’s take a deeper look at one company’s entry path and its wholly owned subsidiary in China. Embraer is the largest aircraft maker in Brazil and one of the largest in the world. Embraer chose to enter China as its first foreign market, using the joint-venture entry mode. In 2003, Embraer and the Aviation Industry Corporation of China jointly started the Harbin Embraer Aircraft Industry. A year later, Harbin Embraer began manufacturing aircraft.

In 2010, Embraer announced the opening of its first subsidiary in China. The subsidiary, called Embraer China Aircraft Technical Services Co. Ltd., will provide logistics and spare-parts sales, as well as consulting services regarding technical issues and flight operations, for Embraer aircraft in China (both for existing aircraft and those on order). Embraer will invest $18 million into the subsidiary with a goal of strengthening its local customer support, given the steady growth of its business in China.

Guan Dongyuan, president of Embraer China and CEO of the subsidiary, said the establishment of Embraer China Aircraft Technical Services demonstrates the company’s “long-term commitment and confidence in the growing Chinese aviation market.”17

12.5.3 Building Long-Term Relationships

Developing a good relationship with regulators in target countries helps with the long-term entry strategy. Building these relationships may include keeping people in the countries long enough to form good ties, since a deal negotiated with one person may fall apart if that person returns too quickly to headquarters.

Did You Know: Guanxi

One of the most important cultural factors in China is guanxi (pronounced guan shi), which is loosely defined as a connection based on reciprocity. Even when just meeting a new company or potential partner, it’s best to have an introduction from a common business partner, vendor, or supplier—someone the Chinese will respect. China is a relationship-based society. Relationships extend well beyond the personal side and can drive business as well. With guanxi, a person invests with relationships much like one would invest with capital. In a sense, it’s akin to the Western phrase “You owe me one.”

Guanxi can potentially be beneficial or harmful. At its best, it can help foster strong, harmonious relationships with corporate and government contacts. At its worst, it can encourage bribery and corruption. Whatever the case, companies without guanxi won’t accomplish much in the Chinese market. Many companies address this need by entering into the Chinese market in a collaborative arrangement with a local Chinese company. This entry option has also been a useful way to circumvent regulations governing bribery and corruption, but it can raise ethical questions, particularly for American and Western companies that have a different cultural perspective on gift giving and bribery.

Mini Case: Coca-Cola and Illy Caffé18

In March 2008, the Coca-Cola company and Illy Caffé Spa finalized a joint venture and launched a premium ready-to-drink espresso-based coffee beverage. The joint venture, Ilko Coffee International, was created to bring three ready-to-drink coffee products—Caffè, an Italian chilled espresso-based coffee; Cappuccino, an intense espresso, blended with milk and dark cacao; and Latte Macchiato, a smooth espresso, swirled with milk—to consumers in 10 European countries. The products will be available in stylish, premium cans (150 ml for Caffè and 200 ml for the milk variants). All three offerings will be available in 10 European Coca-Cola Hellenic markets including Austria, Croatia, Greece, and Ukraine. Additional countries in Europe, Asia, North America, Eurasia, and the Pacific were slated for expansion into 2009.

The Coca-Cola Company is the world’s largest beverage company. Along with Coca-Cola, recognized as the world’s most valuable brand, the company markets four of the world’s top five nonalcoholic sparkling brands, including Diet Coke, Fanta, Sprite, and a wide range of other beverages, including diet and light beverages, waters, juices and juice drinks, teas, coffees, and energy and sports drinks. Through the world’s largest beverage distribution system, consumers in more than 200 countries enjoy the company’s beverages at a rate of 1.5 billion servings each day.

Based in Trieste, Italy, Illy Caffé produces and markets a unique blend of espresso coffee under a single brand leader in quality. Over 6 million cups of Illy espresso coffee are enjoyed every day. Illy is sold in over 140 countries around the world and is available in more than 50,000 of the best restaurants and coffee bars. Illy buys green coffee directly from the growers of the highest quality Arabica through partnerships based on the mutual creation of value. The Trieste-based company fosters long-term collaborations with the world’s best coffee growers—in Brazil, Central America, India, and Africa—providing know-how and technology and offering above-market prices.

In summary, when deciding which mode of entry to choose, companies should ask themselves two key questions:

- How much of our resources are we willing to commit? The fewer the resources (i.e., money, time, and expertise) the company wants (or can afford) to devote, the better it is for the company to enter the foreign market on a contractual basis—through licensing, franchising, management contracts, or turnkey projects.

- How much control do we wish to retain? The more control a company wants, the better off it is establishing or buying a wholly owned subsidiary or, at least, entering via a joint venture with carefully delineated responsibilities and accountabilities between the partner companies.

Regardless of which entry strategy a company chooses, several factors are always important.

- Cultural and linguistic differences. These affect all relationships and interactions inside the company, with customers, and with the government. Understanding the local business culture is critical to success.

- Quality and training of local contacts and/or employees. Evaluating skill sets and then determining if the local staff is qualified is a key factor for success.

- Political and economic issues. Policy can change frequently, and companies need to determine what level of investment they’re willing to make, what’s required to make this investment, and how much of their earnings they can repatriate.

- Experience of the partner company. Assessing the experience of the partner company in the market—with the product and in dealing with foreign companies—is essential in selecting the right local partner.

Companies seeking to enter a foreign market need to do the following:

- Research the foreign market thoroughly and learn about the country and its culture.

- Understand the unique business and regulatory relationships that impact their industry.

- Use the Internet to identify and communicate with appropriate foreign trade corporations in the country or with their own government’s embassy in that country. Each embassy has its own trade and commercial desk. For example, the US Embassy has a foreign commercial desk with officers who assist US companies on how best to enter the local market. These resources are best for smaller companies. Larger companies, with more money and resources, usually hire top consultants to do this for them. They’re also able to have a dedicated team assigned to the foreign country that can travel the country frequently for the later-stage entry strategies that involve investment.

Once a company has decided to enter the foreign market, it needs to spend some time learning about the local business culture and how to operate within it.

Entrepreneurship and Strategy

The Chinese have a “Why not me?” attitude. As Edward Tse, author of The China Strategy: Harnessing the Power of the World’s Fastest-Growing Economy, explains, this means that “in all corners of China, there will be people asking, ‘If Li Ka-shing [the chairman of Cheung Kong Holdings] can be so wealthy, if Bill Gates or Warren Buffett can be so successful, why not me?’ This cuts across China’s demographic profiles: from people in big cities to people in smaller cities or rural areas, from older to younger people. There is a huge dynamism among them.”19 Tse sees entrepreneurial China as “entrepreneurial people at the grassroots level who are very independent-minded. They’re very quick on their feet. They’re prone to fearless experimentation: imitating other companies here and there, trying new ideas, and then, if they fail, rapidly adapting and moving on.” As a result, he sees China becoming not only a very large consumer market but also a strong innovator. Therefore, he advises US firms to enter China sooner rather than later so that they can take advantage of the opportunities there. Tse says, “Companies are coming to realize that they need to integrate more and more of their value chains into China and India. They need to be close to these markets, because of their size. They need the ability to understand the needs of their customers in emerging markets, and turn them into product and service offerings quickly.”20

References:

- Fine Waters Media, “Bottled Water of France,” http://www.finewaters.com/Bottled_Water/France/Evian.asp (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed May 25, 2006).

- H. Frederick Gale, “China’s Growing Affluence: How Food Markets Are Responding” (U.S. Department of Agriculture, June 2003), http://www.ers.usda.gov/Amberwaves/June03/Features/ChinasGrowingAffluence.htm (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed May 25, 2006).

- American Soybean Association, “ASA Testifies on Importance of China Market to U.S. Soybean Exports,” June 22, 2010, http://www.soygrowers.com/newsroom/releases/2010_releases/r062210.htm (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed August 21, 2011).

- Gary Gereffi and Stacey Frederick, “The Global Apparel Value Chain, Trade and the Crisis: Challenges and Opportunities for Developing Countries,” The World Bank, Development Research Group, Trade and Integration Team, April 2010, http://www.iadb.org/intal/intalcdi/PE/2010/05413.pdf (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed August 21, 2011).

- Viacom International, “Viacom Announces a Strategic Alliance for Chinese Content Production with Beijing Television (BTV),” October 16, 2004, http://www.viacom.com/press.tin?ixPressRelease=80454169 (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site..

- Liz Borod, “DA! To the Good Life,” Folio, September 1, 2004, http://www.keepmedia.com/pubs/Folio/2004/09/01/574543?ba=m&bi=1&bp=7 (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed May 25, 2006); Jill Garbi, “Cosmo Girl Goes to Israel,” Folio, November 1, 2003, http://www.keepmedia.com/pubs/Folio/2003/11/01/293597?ba=m&bi=0&bp=7 (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed May 25, 2006); Liz Borod, “A Passage to India,” Folio, August 1, 2004, http://www.keepmedia.com/pubs/Forbes/2000/10/30/1017010?ba=a&bi=1&bp=7 (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed May 25, 2006); Jill Garbi, “A Sleeping Media Giant?” Folio, January 1, 2004, http://www.keepmedia.com/pubs/Folio/2004/01/01/340826?ba=m&bi=0&bp=7 (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed May 25, 2006).

- Michael Mandel, “The Real Cost of Offshoring,” Bloomberg BusinessWeek, June 28, 2007, http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/07_25/b4039001.htm (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site., (accessed August 21, 2011).

- “Global 500,” Fortune (CNNMoney), http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/global500/2010/full_list/ (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed August 21, 2011).

- James C. Morgan and J. Jeffrey Morgan, Cracking the Japanese Market (New York: Free Press, 1991), 102.

- “Glocalization Examples—Think Globally and Act Locally,” CaseStudyInc.com, http://www.casestudyinc.com/glocalization-examples-think-globally-and-act-locally (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed August 21, 2011).

- McDonald’s India, “Respect for Local Culture,” http://www.mcdonaldsindia.com/loccul.htm (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed May 25, 2006).

- McDonald’s Corp., “A Taste of McDonald’s Around the World,” media.mcdonalds.com, http://www.media.mcdonalds.com/secured/products/international (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed May 25, 2006).

- “Glocalization Examples—Think Globally and Act Locally,” CaseStudyInc.com, http://www.casestudyinc.com/glocalization-examples-think-globally-and-act-locally (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed August 21, 2011).

- James C. Morgan and J. Jeffrey Morgan, Cracking the Japanese Market (New York: Free Press, 1991), 117.

- Anne O. Krueger, “Supporting Globalization” (remarks, 2002 Eisenhower National Security Conference on “National Security for the 21st Century: Anticipating Challenges, Seizing Opportunities, Building Capabilities,” September 26, 2002), http://www.imf.org/external/np/speeches/2002/092602a.htm (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. (accessed May 25, 2006).

- Shaker A. Zahra, R. Duane Ireland, and Michael A. Hitt, “International Expansion by New Venture Firms: International Diversity, Mode of Market Entry, Technological Learning, and Performance,”

Academy of Management Journal 43, no. 5 (October 2000): 925–50.

- David A. Ricks, Blunders in International Business (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 1999), 101.

- Michael E. Porter and Mark R. Kramer, “The Big Idea: Creating Shared Value,” Harvard Business Review, January–February 2011, accessed January 23, 2011, http://hbr.org/2011/01/the-big-idea-creating-shared-value/ar/pr.

- Michael E. Porter and Mark R. Kramer, “The Big Idea: Creating Shared Value,” Harvard Business Review, January–February 2011, accessed January 23, 2011, http://hbr.org/2011/01/the-big-idea-creating-shared-value/ar/pr.

- Andrew J. Cassey, “Analyzing the Export Flow from Texas to Mexico,” StaffPAPERS: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, No. 11, October 2010, accessed February 14, 2011, http://www.dallasfed.org/research/staff/2010/staff1003.pdf.

- “The Euro,” European Commission, accessed February 11, 2011, http://ec.europa.eu/euro/index_en.html.

- Steve Steinhilber, Strategic Alliances (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2008), 113.

- “ASAP Releases Winners of 2010 Alliance Excellence Awards,” Association for Strategic Alliance Professionals, September 2, 2010, accessed February 12, 2011, http://newslife.us/technology/mobile/ASAP-Releases-Winners-of-2010-Alliance-Excellence-Awards.

- David A. Ricks, Blunders in International Business (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 1999), 101.

- Steve Steinhilber, Strategic Alliances(Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2008), 125.

- “ASAP Releases Winners of 2010 Alliance Excellence Awards,” Association for Strategic Alliance Professionals, September 2, 2010, accessed September 20, 2010, http://newslife.us/technology/mobile/ASAP-Releases-Winners-of-2010-Alliance-Excellence-Awards.

- “Playing on a Global Stage: Asian Firms See a New Strategy in Acquisitions Abroad and at Home,” Knowledge@Wharton, April 28, 2010, accessed January 15, 2011, http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=2473.

- “Playing on a Global Stage: Asian Firms See a New Strategy in Acquisitions Abroad and at Home,” Knowledge@Wharton, April 28, 2010, accessed January 15, 2011, http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=2473.

- “Playing on a Global Stage: Asian Firms See a New Strategy in Acquisitions Abroad and at Home,” Knowledge@Wharton, April 28, 2010, accessed January 15, 2011, http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=2473.

- Annual revenue in 2008 was $23.5 billion, of which 60 percent was international. Source: Suzanne Kapner, “Making Dough,” Fortune, August 17, 2009, 14.

- Source: Carol Matlack, “The Peril and Promise of Investing in Russia,” BusinessWeek, October 5, 2009, 48–51.

- Source: United Press International, “Brazil’s Embraer Expands Aircraft Business into China,” July 7, 2010, accessed August 27, 2010, http://www.upi.com/Business_News/2010/07/07/Brazils-Embraer-expands-aircraft-business-into-China/UPI-10511278532701.

- http://www.thecoca-colacompany.com/; http://www.illy.com/

- Art Kleiner, “Getting China Right,” Strategy and Business, March 22, 2010, accessed January 23, 2011, http://www.strategy-business.com/article/00026?pg=al.

- Art Kleiner, “Getting China Right,” Strategy and Business, March 22, 2010, accessed January 23, 2011, http://www.strategy-business.com/article/00026?pg=al.

Source:

This page is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share-Alike License (Links to an external site) Links to an external site and contains content from a variety of sources published under a variety of open licenses, including:

- Original content contributed by Lumen Learning

- Content(Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. created by Anonymous under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share-Alike License (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site.

- International Business. Authored by: anonymous. Provided by: Lardbucket. Located at: License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- International Business v. 1.0’ published by Saylor Academy, the creator or licensor of this work.

- “Entry Strategies: Modes of Entry”, section 5.3 from the book Global Strategy (v. 1.0) under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

- ‘Fundamentals of Global Strategy v. 1.0’ under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

- Image of Embraer190. Authored by: Antonio Milena. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Embraer#mediaviewer/File:Embraer_190.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

I would like to thank Andy Schmitz for his work in maintaining and improving the HTML versions of these textbooks. This textbook is adapted from his HTML version, and his project can be found here.